PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on 1962 India-China war, J&K accession, caste census and Pokhran nuclear tests. For now, this is available immediately to all ThePrint readers.

Very soon PastForward will be among the premium offerings that go behind a paywall, only available to subscribers. As will Chinascope.

The year was 1964. A man named P.N. Oak set upon an ambitious task – founding the Institute for Rewriting Indian History. Many laughed at him for his theories, which included claims like the Taj Mahal is actually a converted Vedic temple.

Fifty years later, P.N. Oak’s books are bestsellers, says publishing house Hindi Sahitya Sadan. Their most sold book is Oak’s Hindi title, ‘Kya Bharat Ka Itihaas Bharat Ke Shatruon Dwara Likha Gaya Hai?’ Did India’s enemies write the country’s history?

For a long time, historians from the Nehruvian era dominated school history textbooks and university curriculums. But they were accused of being Euro-centric and neglectful of ancient India’s glory. Now, the other side is pushing back — from universities to publishing houses, literature festivals to Twitter and YouTube. Today, history is no longer just an academic debate. It is a political war zone, replete with mud-slinging and name-calling.

Historians differ on everything from ancient India to medieval India, and even the freedom struggle. Was India’s Vedic past the fount of all knowledge? Was medieval India a period of rape and loot or one of syncretism? Some say, the Mughal era gets too much importance in school textbooks, and kingdoms outside the north are least studied. And according to a parliamentary panel in 2021, history textbooks should be continuously updated — and contain knowledge from the Vedas and Bhagavad Gita.

You’d think India has two rival histories. It’s like ‘Israel and Palestine’, says author and historian William Dalrymple. And both histories are busy cancelling each other.

The scorched earth between the two sets of histories came back into national attention when Vikram Sampath, biographer of two volumes on V.D. Savarkar, was trolled for not being a “professional historian” after a debate with Congress MP Shashi Tharoor.

“Just as Savarkar faces cancel culture, it seems like his biographer also faces the same cancel culture and calumny,” Sampath told ThePrint.

History is a ‘scorched earth’ battlefield

The head-butting over history has particularly increased in the past three decades, running parallel to the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). But it would be simplistic to say that it all began with the Ayodhya Ram Mandir movement. The seeds of the clash of ideas were always there – such as archaeologists finding evidence of River Saraswati or Shiva worship in Harappan sites, or debunking Aryan ‘invasion’ theory — manifesting in bits and parts, over time. But now it has burst into the open and is challenging entrenched systems of knowledge like never before.

“Academia is a clique — and anyone who fails their litmus test of scrutiny is an outsider,” Sampath said.

“This isn’t a clash of history,” said historian Tanika Sarkar. “This is a clash of political values. The interest in history exists to promote an idea of India.”

A lot of the fight boils down to technicalities, but history is not just a set of facts. It is the interpretation of those facts. Therein lies the rub.

Hilal Ahmed, associate professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, pointed to Ayodhya as an example of this. “It is a very important question to ask which history you take the side of. It is not a technical, but a moral question,” he said. “What is acceptable? You decide.”

Also read: In JNU, works of Gail Omvedt and Dalit scholars are relegated to ‘underground’ networks

History was always political

History was canonised in India’s academic institutions. And that’s where the clashes are taking place today.

Central universities — and the kind of ethos they maintained — were influenced by politics. India’s leading institution, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) is a prime example.

Set up in 1969 by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her education minister, Syed Nurul Hassan, JNU was established when Gandhi’s government relied on support from the Communist Party of India. The university’s curricula and faculty were, as a result, politically aligned. According to veteran journalist and politician Arun Shourie, the Left, led by Nurul Hassan, “captured” academic institutions and departments of history and archaeology to push a certain narrative.

“Exactly the same thing is happening today. Setting up false gods like Savarkar, or in extreme cases, Godse, will have consequences because it will pervert the values in our society,” he said. “These things become the handmaiden of the worst kind of politics.”

The curious case of Jadunath Sarkar

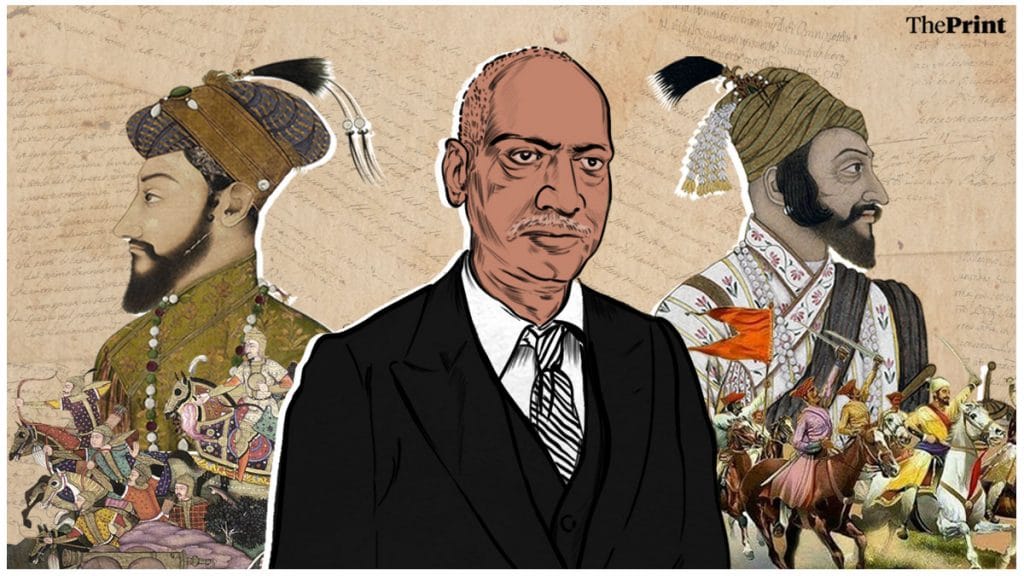

The works of historian Jadunath Sarkar (1870-1958) offer us an important lens into politics and historiography.

Sarkar was instrumental in shaping the way figures like Shivaji and Aurangzeb are pictured in popular imagination — especially because the Aurangzeb-Shivaji binary would come to be an important calling card for Hindu groups.

His interpretation of Mughal history is considered dated by mainstream academia. Dipesh Chakrabarty’s book, The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth, argues that Sarkar’s positions – such as depicting Aurangzeb as a communal bigot – were shaped by the colonial debates of his time. Historians like Sarkar and R.C. Majumdar used religion as a marker of cultural identity, while Leftist historians used class.

However, Hindu groups feel that Sarkar has been maligned by mainstream academia. And they’re not entirely wrong — but ironically, at the time, Hindu groups thought he was disrespectful towards figures like Shivaji. In his 1919 book on Shivaji, Sarkar referred to him as “Shiva,” angering Hindu groups in Maharashtra.

Sarkar ran up against bureaucratic resistance when he wanted to nationalise the archives, but he lost – the archives ultimately became inaccessible to most Indians. He was also maligned by historians like Irfan Habib, whose 1958 doctoral research thesis on agrarian systems in the Mughal era from Oxford did not cite Sarkar’s Fall of Mughal Empire. The few references to him in footnotes refer to the errors in translation and dating events.

But both the political and academic mainstream saw him as a pro-empire historian who was not sufficiently analytical in his approach to history. And they did their best to erase him from public memory. Indira Gandhi’s government and Nurul Hassan set up the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences in Sarkar’s Kolkata house in 1973. They made sure to remove any trace of its former inhabitant – all his objects were taken out and Sarkar’s old papers sent to the National Library.

Cow science in universities

But a lot is changing in India’s central universities. The University Grants Commission (UGC) encouraged all students to take a national exam on cow science in February 2021. A professor allegedly walked out of an interview for an English Literature position at Delhi University after it refused to teach a course on cows. IIT Guwahati followed the lead of other IITs and inaugurated a Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems in November 2021.

Michel Danino, a visiting professor at IIT Gandhinagar, co-ordinates a class on Indian knowledge systems. He teaches courses on Indian systems of ethics, perspectives on Indian civilisation, and an introduction to science and technology in ancient India. However, some students come to his classes with notions about ancient India being a dark, gloomy period with little more than caste and gender oppression.

“If we want young Indians to be proud of India, we have to take them beyond such stereotypes and expose them to authentic material and honest debates; pride, if at all, will follow naturally and will be rooted in genuine understanding,” said Danino.

The science and engineering faculty have been more enthusiastic than his colleagues in the humanities department, he said.

Also read: Nehru said romanticisation of past doesn’t solve today’s problems. India needs to re-read him

Where are India’s Niall Fergusons?

India’s stalwart historians include the likes of Romila Thapar, Bipin Chandra, and Irfan Habib, but decades of neglect has created a gaping deficit in Right-wing scholarship. Now, with the BJP in power, this gap is being felt and contested more than ever. Other countries have popular Right-wing intellectuals like Niall Ferguson: where are India’s Right-wing intellectuals?

“I think India had a much stronger Right-wing intellectual tradition in the early 20th century than what is on display today,” said historian Neeti Nair. “The arguments between a Lajpat Rai, Swami Shraddhanand and Gandhi were on substantive issues, and always conducted with decorum.”

But today, both decorum and mainstream Right-wing intellectuals are in short supply. And Right-wing theories have found a new platform — publishing houses.

Dalrymple, who is also one of the founders and co-directors of the Jaipur Literature Festival, said that the number of serious Right-wing historians was negligible in India, in contrast to universities like Cambridge where Right and Left were almost equally balanced, with top-rank historians on both sides of the political spectrum.

“At Jaipur, we struggled to find serious, articulate Right-wing Indian historians 10-15 years ago. Swapan Dasgupta was really the only one,” he said.

Very few people were writing Indian history the way people wanted to read it, Dalrymple added. Some Indian academics, like members of the Subaltern Studies Group, ended up inadvertently gatekeeping history by writing in such dense academic jargon that it was almost a private language. And this, Dalrymple says, led to a vacuum. Instead, Indian historians seemed to write only for each other, in “dense academese.”

Fighting over dug-up facts

History also moves beyond the written word: archaeologists in India face similar issues.

Like Hilal Ahmed pointed out, the archaeological excavation of Ayodhya reveals the way historians and archaeologists clash over theory — sometimes even physically.

A fight broke out on stage at the third World Archaeological Congress (WAC) in New Delhi in 1994. While international archaeologists watched stunned, the Indian delegation came to blows over the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

Led by B.B. Lal and Swaraj Prakash Gupta, senior archaeologists rushed to the stage to snatch the microphone and stop another delegation of Indian archaeologists from reading a petition condemning the demolition of Babri Masjid. The conference ended in disaster, with the WAC council boycotting the official closing ceremony.

B.B. Lal led an excavation of the Babri Masjid between 1975 and 1980. The excavation confirmed that Ayodhya had been a multicultural site, but found no trace of a Hindu temple.

But in 1990, over ten years later, Lal published an article in the BJP-affiliated magazine Manthan claiming that he had found Hindu temple pillar-bases during the excavation, despite never mentioning it earlier.

“B.B. Lal’s article in Manthan was the original lie,” said archaeologist and anthropologist Ashish Avikunthak.

This argument — whether factual or not — irrevocably changed the narrative of the Babri Masjid.

In his book Bureaucratic Archeology, Avikunthak writes that Lal used “his authority as an eminent ASI archaeologist” to back an “egregious claim.”

Other archaeologists did this too.

Archaeological findings are especially important to establish the existence of a Vedic civilisation before the Indus Valley Civilisation, to prove that India’s civilisational lineage is longer and more robust than any other. And more importantly, Hindu.

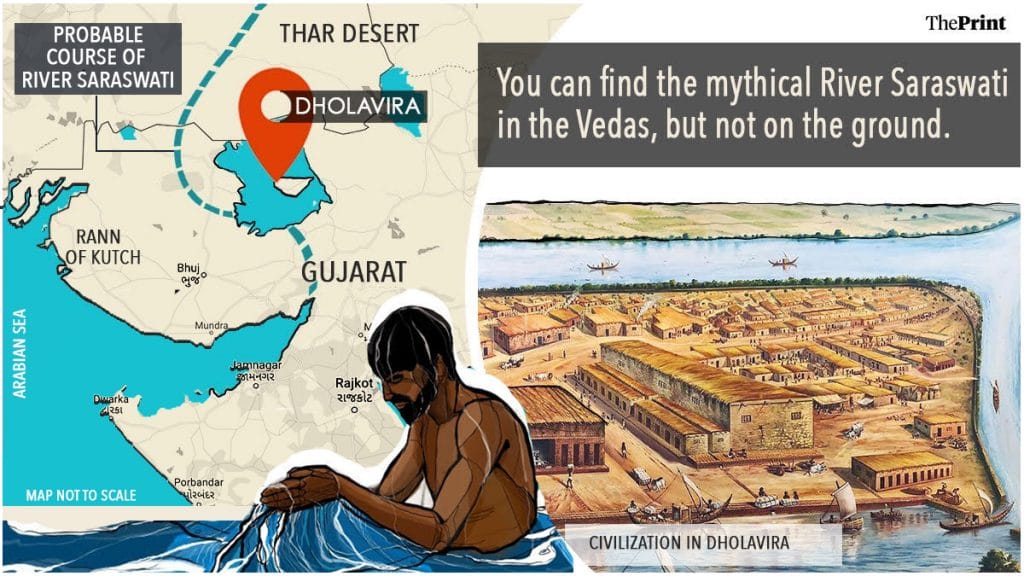

An important lynchpin for this project is the mythical river Saraswati, which appears in the Vedas. The Saraswati Heritage Project was set up in 2002 to establish the location of the river, and senior archaeologists were involved from the beginning. An assistant superintending archaeologist reportedly said that all archaeologists involved — like B.B. Lal, S.P. Gupta and R.S. Bisht — had Right-wing sympathies, and that Gupta lobbied for funding for the project. The excavations lasted only for a year between 2003-04 under the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, and had no significant findings. The project has been revived again.

R.S. Bisht published his excavation report on Gujarat’s Dholavira in the ASI’s journal in 2017, but the paper was taken down because it contained too many personal speculations and terms like the “Saraswati Civilisation.” It hasn’t been published to date.

Maintaining a status quo

It’s not just the tendency to disown or debunk alternate ways of thinking about India’s history. There is one other problem.

The Left has a robust methodology but sometimes neglects or suppresses other modes of thinking, says Dinesh Singh, mathematician and former vice-chancellor of Delhi University. The Hindu Right, on the other hand, has not yet matured in its methodology and its assumptions can be shaky.

“Unfortunately, between the flights of imagination of the Right and the ideological limitations of the Left, history has really suffered in India,” he said.

Singh faced enormous pushback from the Left establishment when DU controversially dropped a famous essay by A.K. Ramanujan – “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five examples and three thoughts on translations”. When the essay was introduced, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) and other Right-wing groups ransacked the history department at DU, and reportedly roughed up then-department head S.Z.H. Jafri.

Other academics have said that universities keep the status quo in place by framing curriculums a certain way — for example, noted historians like Jadunath Sarkar, Neelakant Shastri and R.C. Majumdar were not always part of the history department’s syllabus.

“What we see today in certain varieties of populist Right-wing histories is a total negation of evidence and a purposeful construction of a narrative that enables their political objectives,” said Farhat Hasan, a professor at Delhi University.

But students from the Right were always present on campus, even if they were not as assertive. Today, former JNU students who ideologically align with the Right say that they were deliberately sidelined.

“Students who had different perspectives were pressured on campus. They got fewer marks, and their PhD thesis was delayed if professors didn’t like their research,” said Saurabh Sharma, assistant professor at JNU and former joint secretary of the JNUSU. He joined the ABVP in 2013.

“By hook or by crook, some professors make students research topics that are directly influenced by their ideology. Students are compelled to do it for their academic career.”

Universities also maintain status quo by denying admissions, fellowships, and promotions. One example is K.P. Dhurandhar, who was denied professorship at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development at JNU. This was because he was a member of the ABVP, according to Dr Rashmi Das, editor, TelecomLive & InfraLive, and former JNUSU general secretary.

Also read: The tale of two Ayodhya archaeologists who changed the way we dig up India’s Hindu history

The hidden is now the mainstream

The ABVP used to hold their own lectures on nationalism for their cadre on JNU campus — separate from official classes taught by professors like Tanika Sarkar. These lectures were voluntary and held after class hours.

Members discussed topics like how “real” Indian history is different from the colonial British narrative, and India’s present potential given its undiscovered past. They also discussed theories like the Aryan invasion and how to disprove it.

This ‘basement history’ is now a favourite accessory of new Lutyens’ Delhi.

It took a long time for someone like then-BJP minister Babul Supriyo to attend an event organised by the ABVP at Jadavpur University, a Left bastion. However, he was heckled by agitating students, which triggered student violence in 2019.

But the frowned-upon ‘other’ is now in power and has cancel power.

Recently, JNU cancelled a webinar in October 2021 organised by the Centre for Women’s Studies on the situation in Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370 after some teachers and students protested. Vice-chancellor M. Jagadesh Kumar called the subject “objectionable” and “provocative,” and ordered an inquiry into the matter. The JNU teachers’ forum tweeted that they opposed the webinar as “anti-national”. In 2016, a BJP-affiliated group filed police cases against JNU professor Nivedita Menon for a speech she made on campus, calling her views “anti-national.” Academic Anand Teltumbde was booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for allegedly encouraging the Bhima Koregaon event and has been in jail since April 2020.

Like Shourie told ThePrint, what the Right-wing is doing in central universities today is exactly what the Left did in the ’60s, ’70s, and early 1980s.

Publishers step in to fill the void

Meanwhile, a Right-wing renaissance has been taking place in the publishing industry. From Tripurdaman Singh and Rajiv Mantri to Jaitirth Rao and Vikram Sampath, there’s a mushrooming of authors writing on subjects and personalities from a different lens. It’s easy to dismiss them as ‘Sanghi historians’, but this is a product of decades of being kept out.

And publishers are dishing out titles to feed the rising demand for historical non-fiction.

“There is certainly a hunger for storytelling and for ‘discovering’ the past,” said V.K. Kartika, a publisher at Westland who was formerly with HarperCollins. Both of these have resulted in an increase in historical narratives across the political spectrum.

“Legacy authors like Shashi Tharoor and Ram Guha continue to do well, but there’s a growing market for younger, newer voices in the historical space, as audiences are not just going after the stalwarts,” said Tarini Uppal, Associate Commissioning Editor at Penguin India, citing Vinay Sitapati’s published works with Penguin as an example.

She added that young authors are no longer writing dry history like the previous generation.

Also read: Congratulations liberals, for another self-goal in forcing Bloomsbury on Delhi riots book

Independent presses publish the rest

But this ‘rise of the rest’ is not without some resistance. Publishing house Bloomsbury pulled out of publishing the controversial Delhi Riots 2020: The Untold Story, co-authored by Monika Arora.

Arora told ThePrint that Bloomsbury was under pressure from “Islamists and Leftists” not to publish the book. The authors then turned to independent publishing house Garuda Prakashan, established in 2017.

“We had never been approached by an author under such circumstances before. Delhi Riots was deplatformed at the last minute and withdrawn, not due to the content but due to agenda-driven politics by various groups,” said Garuda Prakashan co-founder and COO Ankur Pathak. Garuda’s most popular releases are French historian and Hindutva activist Francois Gautier’s An Entirely New History of India and English Literature postgrad Manoshi Sinha Rawal’s Saffron Swords.

Journals to the rescue

Writers also found platforms in academic journals like Voice of India and Itihas Darpan — both of which have deep ties to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

Itihas Darpan is published by the Akhil Bharatiya Itihas Sankalan Yojana (ABISY), a think tank subsidiary of the RSS that is dedicated to writing Indian history from a nationalist perspective. Set up in 1994, ABISY was founded to correct “distortions” in Indian history — like Bhagat Singh being portrayed “as a terrorist,” or Akbar being called “Great.” According to ABISY’s secretary, the “role of history is nation-building.”

Voice of India was established in 1981 by public historians like Sita Ram Goel, who is known for his book Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them, which lists 2,000 mosques built on the site of desecrated temples. The book was co-authored with Arun Shourie.

Goel had previously written for Organiser, an unofficial RSS-affiliated magazine that was set up in 1947. While former editors like Seshadri Chari, who is on the National Executive Committee, say that the magazine is not an official publication like the People’s Democracy is for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He also maintains that the writers “take pride in espousing the ideology of the RSS.”

Author of Gita Press and The Making of Hindu India, Akshaya Mukul said, “You simply cannot be writing history from a perceived feeling of being wronged by Leftists.”

There’s also no clarity on their fact-checking and peer-review processes, unlike other academic journals. As a result, these theories are not academically discussed or contested. Chari says that the Organiser doesn’t have a peer-reviewing or editorial cross-checking process in place.

Also read: Are you anti-national, seditious, or simply inconvenient? Your bookshelf holds the answer

Social media historians

It’s no surprise that speculating over what happened in the past moved from the academic ivory tower to a far more accessible echo chamber: social media.

History-focussed content is now prominent on Twitter and YouTube. Social media brings its own risks of poor gatekeeping. Twitter accounts like TrueIndology have been suspended for tweeting misinformation and distorting historical facts.

“[These accounts] completely concoct cock-and-bull stories about any event or individual and have far more currency among people who don’t have easy access to unbiased books,” Mukul said.

However, Twitter historians and WhatsApp forwards don’t represent popular history — but they do encourage greater public interaction with history.

Vikram Sampath pointed out that social media also gives sidelined historians the freedom to contradict mainstream interpretations of history, but added that it is no substitute for real and lasting scholarship.

For instance, public figures like Shashi Tharoor and Yogendra Yadav received pushback for sharing a painting of Krishna pointing at the Eid moon.

Your Great Man vs My Great Man

The idea of India is changing. People are resisting the notion that there should only be one idea. So, to craft a new national identity, history must be re-imagined and stifled histories must be brought to light.

Tanika Sarkar says that historians on both sides of the spectrum today subscribe to the Great Man Theory – that history is defined by the acts of heroes, conquerors, and leaders.

Historians like Prachi Deshpande and Gyanendra Pandey have written about the tendency to ascribe glory to a version of events to instill pride in India’s history. And now, the ideological fracture pits these ‘great men’ against each other — inevitably elevating one and denigrating the other.

“Characteristically, their histories move around the hero-villain axis, and lack the tools and the resolve to ask larger issues of historical change,” said Farhat Hasan.

“It’s not a new position, we’ve always been a nation of hero-worshippers,” said Vikram Sampath. “Ashoka the Great, Akbar the Great…we’ve given a larger-than-life image to so many figures, including people like Nehru and Gandhi. Now, the axis of ‘greatness’ is expanding and more people are being recognised, upsetting existing status quo positions.”

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)