The Taliban has persecuted me unremittingly. I had escaped to Pakistan earlier but was caught. Then I escaped again a month later. Kakoli came to see me before my second escape, and seeing her reminded me of how a man often sleeps with two wives in the same bed. My body recoiled in revulsion. How twisted their conjugal life is. The thought disturbs me constantly. Thinking of the woman who is forced to become the second victim of the night makes me rebel. This is unbearable humiliation for a woman.

I have repeatedly invited danger upon myself in trying to gain plaudits. Because people at home like my cooking, my brothers-in-law often invite guests and force me to cook for them, beating me up if I refuse.

Torturing women is an act of great valour for any man in this society. I have no space in my husband’s house for a moment’s quiet reflection. No woman in Afghanistan has any space to think or analyse. Eat, chat, and go into your rooms with lanterns as soon as it’s dark. Battle against poverty and unemployment. Fight the stifling shadow of traditions and fundamentalism and ignorance and lack of education. How will seeds of new ideas sprout here? How will anyone learn to think differently?

Privacy is one of the greatest gifts of modern civilisation, but no home in Afghanistan offers it. This suffocating life stands in the same place every day, refusing to move on.

There’s no privacy, but there’s loneliness. Ironic, isn’t it? In six years, the Kabul evenings have not once brought me a spring breeze. It has never felt romantic here. Only insufferable. Especially from December to February, when it snows every evening. There’s darkness everywhere—not a song in anyone’s heart, not a word of love in anyone’s head. All I want is to go back to my room in Kolkata and sing along with Tagore’s songs or read Nazrul’s or Jibanananda Das’s poetry.

Had they been born in Afghanistan, would Kazi Nazrul or Jibanananda Das have become poets? For all you know, they wouldn’t even have been capable of writing a letter. As men, all they would scream is, ‘Bring me food. Wash the clothes. Light the lamp. Give birth. Clean the snow. Submit your body at night.’

Initially, the sex life in Afghanistan appeared repulsive to me; it made me nauseous. But after six years, even that has become attractive. There is probably some sort of perversion in the relationship between women and men in this country, or so it seems to me. But in this perversion lies everyone’s pleasure, perhaps their only form of entertainment. Life here is nothing but war and arid deserts. Maybe sexual perversion is the only oasis. I try to remain indifferent to the harshness of sex here, I try to preserve the faith and the values, the likes and dislikes, of my Bengali self. And this has been possible only because of Jaanbaz.

Sometimes I wonder—the extreme torture the Taliban submitted me to, the way they beat me till I was half-dead, even tearing off my clothes—was it all because I offer primary medical treatment to people? Does the desire to punish me stem from my sowing the seeds of rebellion among people? Is there no other provocation? I feel there are other reasons. To the Taliban, I am a kafir. A Hindu, someone from another religion. A Bengali. A woman. And the Koran has repeatedly warned against marrying a kafir.

Also read: No male ‘chaperone’ = no existence. Life under Taliban rule for Afghan women, in their own words

I escape a few days after being persecuted to inhuman lengths by the Taliban. The first time, they capture me in Pakistan and lock me up in a room. My brothers-in-law stand guard round the clock. When I escape a second time, I run all night, through graveyards and across ditches, and am about to get on a train at dawn when the Taliban capture me again. Then there is a trial, and I am sentenced to death.

The Koran stipulates death for women like me. I am falsely accused of being an adulteress. Because I had the audacity to defy their authority and escape twice.

Also read: Crushed dreams, threats, marriage ‘for safety’ — what life is like for educated Afghan women

It is 22 July 1995. I was captured two days ago. Even my second attempt to escape did not secure my freedom. The trial took place at my husband’s nephew Rafiq’s house. Fifteen members of the Taliban and several of my husband’s uncles were present. After day-long discussions on the 21st, the judgement was delivered. I was to be shot dead. Jaanbaz’s uncles made many requests, they pleaded with the Taliban to wait until Jaanbaz returned.

The Taliban did not entertain them. They said: ‘We cannot allow our nation to come to harm because of a kafir. This will bring our women a bad name. The whole world will point its finger at us accusingly. They will say we have insulted Islam, and we have insulted the Koran, which clearly says that when a woman is wayward, try at first to restrain her. But if she refuses to be disciplined, kill her. Else it will be a sin. And those who accept this waywardness are sinners and will go to hell. Therefore, she must die, or we will be guilty of flouting the holy tenets of Islam.’

So it has been decided that I will be shot at twelve seconds past forty-five minutes past eleven on the morning of 22 July. Apparently, it is an ideal time for the execution of a death penalty. Last night, preparations were made for my last meal. Rafiq’s wife and daughters-in-law were crying for me. The Taliban and my in-laws were downstairs in the guest room. Dranai Chacha, Mamai Chacha, Abdullah, Bismillah—they were all present. After dinner, Siddique told me that no one in the family ate properly.

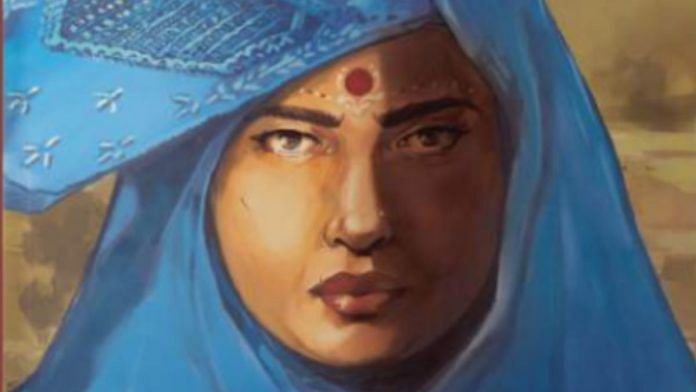

This excerpt from The Taliban and I by Sushmita Bandyopadhyay has been published with permission from Eka.

This excerpt from The Taliban and I by Sushmita Bandyopadhyay has been published with permission from Eka.