The other day when I was scrolling through my Instagram feed, I came across a couple of posts from one of my favourite food accounts. One of them was about sweet and savoury scones, which I loved. The other was about a chicken rogan josh. It turns out that a rogan josh made with chicken instead of lamb I’ll forgive, but a recipe that calls for tomatoes and calls itself a rogan josh, I most certainly won’t.

What did I do? I of the strict ‘no-comments-on-public-posts’ rule, what did I do? Obviously, I commented (almost), eloquently expressing my righteous outrage. I believe the comment started with the following words: Oh for the love of god!

All very calm and measured. You know.

But it got me thinking, again, about why I get so cross about these things – tomatoes in rogan josh, or bay leaves or garam masala powder in what claim to be Kashmiri recipes.

I’d like to think that I’m a fairly tolerant person. I’ve always embraced change. I’ve lived in different cities, become intimate with and fervently admired various cultures, celebrated the coming together of disparate and even opposing points of view. So why do I find it so hard, impossible even, to shrug my shoulders and say, ‘Oh well, makes for a change’, when I see people making nun chai tarts (from Kashmiri green tea) or Kashmiri biryani? Why does every bay leaf, every tomato, every spoonful of sugar in nun chai feel like a personal attack? Why can’t I be more like my Punjabi friend, who once took me to a paratha stand in Delhi that made and sold, of all things, chicken chowmein parathas, and respond with undisguised glee?

I also know that I am not alone in feeling like this. It’s a very Kashmiri thing. Kashmiris are extremely protective of our food, the way it is cooked, served and eaten. The slightest change, especially if it comes from outside, is often perceived as a direct attack, an insult. And there’s outrage: It’s not authentic! That’s not how it’s supposed to be! Or as I so movingly put it under that Insta post, ‘Leave rogan josh alone!’

Palestinian people, I find, are much the same, as are some Jewish people. All are fairly obsessed with preserving the authenticity of their food.

But really the question should be: what is authentic? Authenticity-bashing is on point these days, after all. I have by now engaged in more than a few conversations on various social media platforms where people – intelligent, well-informed, often well-intentioned people – will routinely and passionately dismiss the concept of authenticity. This dismissal is especially impassioned when it comes to food, but also adheres to some other markers of identity.

Nothing is authentic, they say. And, by extension, everything is. Your version of your favourite food is as authentic as mine, even though the two of them may be wildly different from each other. Often, these naysayers argue, our versions or definitions of authenticity are formed by our childhood introductions to those foods, clothes or other markers. It’s the way a particular dish was made in your parents’ kitchen that automatically becomes your idea of the authentic version.

So, no one can claim theirs is the definitive authentic version. And by extension everyone can claim theirs is. Authenticity as a concept is thus inherently false and meaningless.

Very good points all of them. And yet, and yet…

Food, like language, is one of the most important and obvious markers of cultural identity. And food, like language and culture, is intensely political. Authenticity, then, is not just a nice, catch-all term. For some, it becomes a matter of survival. Let me elaborate.

In fact, let me go back to my Punjabi friend, the one who loves chicken chowmein parathas and I’m sure would not blink even if I suggested we eat momos with makki ki roti. I love her, obviously, but I also envy the self-assurance with which she navigates the world. She is so sure of her place, the place of her culture, her language, her clothes, her food in the world she inhabits that she is open to everything. Nothing is a threat.

By contrast, to someone who comes from a people torn apart by conflict for generations, someone who is unsure of everything, including whether or not they will return home alive in the evening, everything is a threat. Every time someone tries to add a bay leaf to ‘my food’, it feels like a direct assault precisely because so much of what comprises ‘my identity’ is already under threat. Kashmiris often talk about their identities being diluted through an erasure of everything that makes them distinct. This includes their language, what they wear, how they sing, celebrate and mourn, what they write, how they read, and above all what they cook and how they eat.

When I was growing up, Kashmiri wasn’t taught in schools, though I understand this has changed now. Pherans had given way to shalwar kameezes, and brides wore lehenga cholis on their big days. But one thing that has not changed is our food. It has sometimes been stripped down, as it was during long curfewed months to be sure, but the essentials are still the same. The rogan josh I make in my tiny little kitchen in London is exactly the same as my mother made in her various kitchens, in Kashmir and outside, and her mother made on a wooden stove in hers. It’s mine, ours, and I’m sorry but you cannot add tomatoes, bay leaves and garam masala powder to it. Thanks.

And sure, of course food, like every other marker of identity, evolves over time. It must, if it wants to survive. My grandmother cooked over a mud stove fired by wood. My mother on a gas stove attached to a cylinder. My little kitchen in London has a gas hob and an electric oven. And sure, of course there were times, especially when we no longer lived in Kashmir, when my mother had to improvise – regular chillies instead of Kashmiri chillies, brown cumin instead of black, onions instead of shallots – something I end up doing too.

What is also true is that there are regional variations in how Kashmiri food is cooked. Sometimes the same dish will be cooked somewhat differently even in the same region. Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims will use different spices for the same dish. The point is that variation, improvisation, innovation even, is not a problem as long as it comes from within. As far as most Kashmiris are concerned, all of these variations and versions are authentic.

I have had conversations with some of my Palestinian friends about why it is important to preserve exactly how a particular dish is cooked, and the parallels and the echoes are fascinating.

And of course while there is much that’s different between Kashmiris and Palestinians, and their respective situations, in a world where they seem to have such little control over their individual and collective lives and lands, where from their point of view, every marker of their identity seems to make them a target, food is one thing they still have control over. One thing they can reject. One thing they can preserve. One thing they can pass on to future generations.

So, although my son was born and has lived all his life in London, even he knows that there are no tomatoes in rogan josh. Because that wouldn’t be authentic. And at this point authenticity is the only thing we have.

Also Read: How Kannadigas justify adding jaggery in Sambar—Sea level, idli-fermentation speed

Rogan Josh – Our Family Recipe

Ingredients

1 kg lamb (You could use any cut, but chops are great – meat, fat, bone. Oh yeah.)

3–4 shallots, medium, finely sliced

3–4 fat cloves of garlic, minced

1 inch ginger root, minced (optional)

400–500g yoghurt

Oil for cooking (I use olive oil but vegetable oil is fine. As is ghee. Whatever rocks your boat.)

Whole spices: (Note: Kashmiri cooking is all about whole spices)

5 black cardamoms (because odd numbers are better than even.

Yup.)

5–7 green cardamoms

2–3 black peppercorns

1 clove

1–2 tsp cumin seeds

1 inch stick of cassia

Ground spices:

1–2 tsp fennel powder

1–2 tsp turmeric

1–2 tsp Kashmiri red chilli powder

salt to taste

Method

- Use a thick-bottomed pan, big enough for the amount of lamb. Once the pan is hot, add a generous amount of oil. Add the shallots and cook on a high flame for a few minutes until they are soft and translucent.

- Add the meat and fry until golden brown.

- Add all the whole spices and fry until it all smells gorgeous (around 5–6 minutes). If you, like my son, don’t like ‘seeds’ in your curry or prefer a slightly more intense flavour, then all you need to do is dry roast the whole spices (except cassia) and grind them in a pestle and mortar before adding to the meat. Boom.

- Next, add all of the ground spices to the pan and fry. Add garlic and ginger. Stir well, making sure to coat all of your meat with the spices.

- Now is the time to start adding the yoghurt to the pan, a little at a time, making sure its cooked down completely before adding more.

- Once all the yoghurt is added and cooked down, add a cup of water and bring the pan to a boil. Add salt to taste. Let it cook on a high flame for a couple of minutes before turning the heat right down.

- Put the lid on and forget about it for about an hour and a half until the meat is terribly tender and falling off the bone, and the gravy is rich and thick and beautiful.

- Garnish with fresh coriander and serve with lots of steamed white rice.

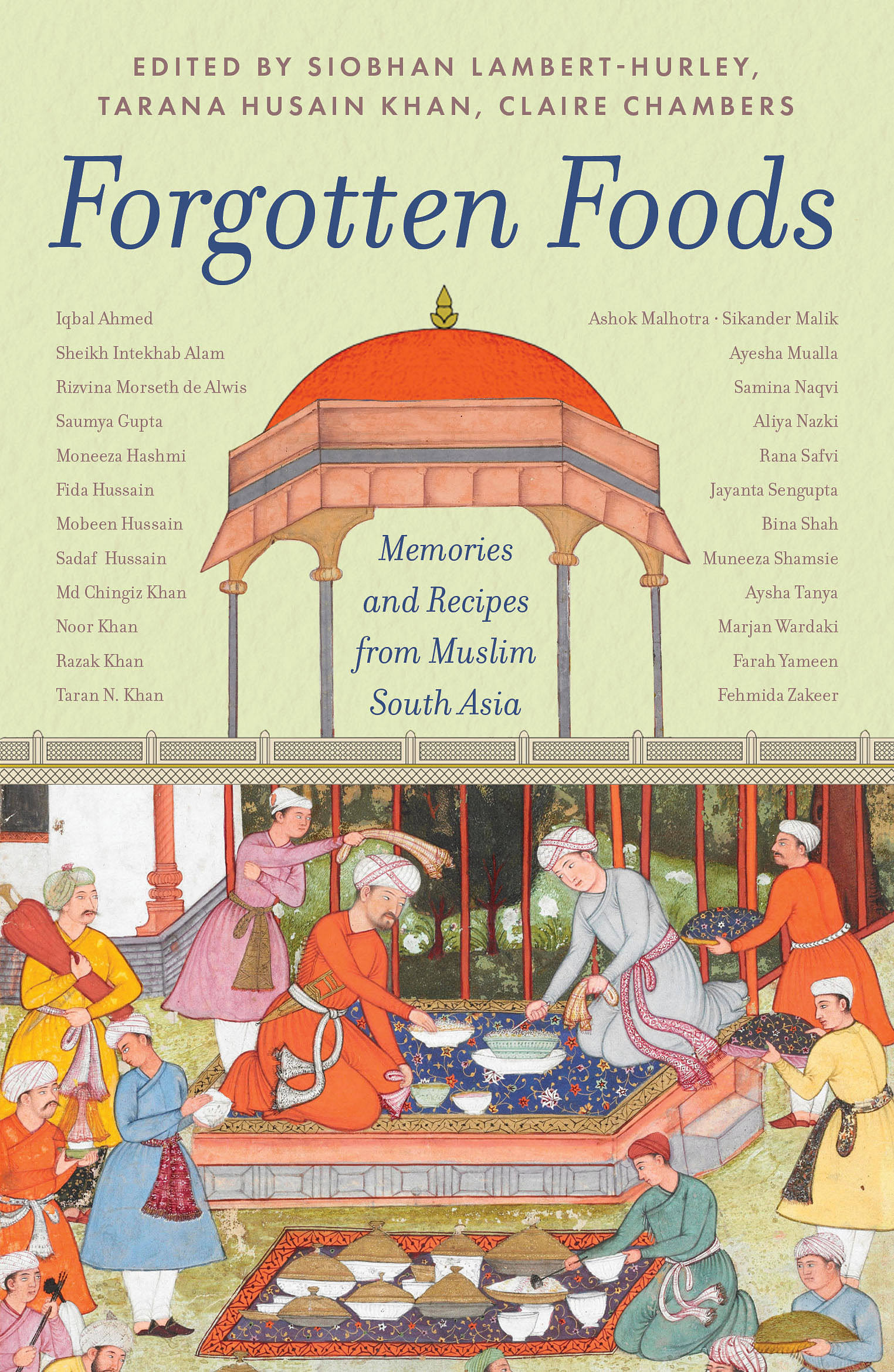

This excerpt from Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia edited by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Tarana Husain Khan and Claire Chambers has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan India.

This excerpt from Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia edited by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Tarana Husain Khan and Claire Chambers has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan India.