Cut to three decades later, a time dominated by three men with a common surname, each appealing to a different constituency with consistency and charm. The evolution of the three Khans, their personal lives, public spats and professional accomplishments have held India spellbound. But the nation has changed, unleashing forces both positive and pessimistic. Where there were easy definitions, there are divisions; where there was a definitive national identity, there are multiple diversities; and where there was one kind of audience, there are as many as there are platforms.

As we enter the third decade of the century, will Ranveer Singh and Ayushmann Khurrana become the superheroes and everymen of our paradoxical times? India is not the country it was when the Khans burst on to the screen, or even when they were at their peak. Noted academic Ashis Nandy told me recently that he doubts whether such a moment in India’s history will return where three Muslims could be unparalleled cultural heroes. He believes a large majority of Indians have travelled too far down the road of regarding the Muslim as the ‘other’.

Also, the business of Bollywood heroes is one of diminishing returns. The Khans at their finest could never repeat what Amitabh Bachchan had achieved at the height of his fame. Any new star will find it impossible to imitate the universality of the Khans. The audience is far less tolerant of ordinary scripts bolstered by star power. It demands more compelling narratives. It has an increasingly schizophrenic attitude to the consumption of glamour—those whose controversies it follows are not necessarily the ones whose movies it watches.

In today’s Bollywood, nothing is certain. You can bare your bottom, dance frenetically in Paris, and mouth ridiculous dialogue that passes for cool, but you cannot get a Befikre (2016) to succeed, even though it is directed by Mumbai’s most powerful producer, Aditya Chopra. Ranveer Singh realised this when the film that was studio-designed to get him to slip into Shah Rukh Khan’s shoes flopped. Ranbir Kapoor, the other star touted to replace the Khans, had become aware of this even earlier, when his movies with the two Kashyap brothers—Abhinav Kashyap’s Besharam (2013) and Anurag Kashyap’s Bombay Velvet (2015)— brought his early, hard-won stardom crashing down to earth. Ranbir had perfected the boy-man trope which he initiated in 2009 with the coming-of-age movie, Wake Up Sid!. Directed by Ayan Mukerji, who soon became Ranbir’s best friend, the film established the idea of the boy waiting to be rescued by the woman so that he could become a man. The idea was explored again in Mukerji’s Yeh Jawaani Yeh Diwani (2013) as well as in Karan Johar’s Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016). Raju Hirani’s Sanju (2018) was the ultimate in this line of munna-babies. Ranbir Kapoor’s star waned somewhat because of the prolonged shoot of Ayan Mukerji’s Brahmastra. But a fresh set of movies, starting with the dacoit epic Shamshera, may well restore his lost sheen.

Also Read: Salman Khan: ‘Main Google search mein aata hoon, samajh mein nahi’

Ranveer Singh, once Ranbir’s direct rival, is aware of the fickleness of stardom, but he is both hungry for more and careful about its orchestration. A natural actor, he is a constructed, method star. Indeed, Ranveer is forever in performance mode, boom box for company, energy on high, and an effusive embrace for everyone. Even journalists who have interviewed him at length have rarely been invited into his private space, his ‘apna time’, be it his home or inside his vanity van.

Ranveer’s preparation for his roles has become almost as iconic as that of Aamir Khan. For the role of Kapil Dev in Kabir Khan’s 83, he underwent four months of intensive training, says Khan, learning how to bowl like the World Cup winning captain. Balwinder Singh Sandhu from the 1983 squad was his coach, with Kapil adding his inputs. Kabir Khan calls him a chameleon, saying, ‘He’s that rare actor today who is able to totally and completely transform himself into the character he is portraying. His face seems to change with every character. From Khilji (Padmavat) to Simmba to Gully Boy, we just don’t see the same person—they are three different and unique people on-screen.’ He looks for the key in every character and struggles until he is satisfied with it—while he was preparing to play Khilji, he locked himself up in his new flat in Goregaon for twenty-one days to isolate himself and find the darkness within.

Ranveer takes his celebrity status almost as seriously as he does his acting. His flamboyant suits, witticisms, and networking are all carefully plotted. From the time he attended parties with his boom box to get noticed among a sea of newbies, he has aimed to be the life and soul of every celebration—witness his wild dancing at Sonam Kapoor’s wedding reception with Anil Kapoor, the father of the bride. Equally well-orchestrated is the image he presents as one half of Bollywood’s premier power couple, since his Lake Como wedding to Deepika Padukone. She is higher paid, has worked longer in the industry, and is clearly the bigger star. But he is comfortable enough in his skin to accept this and revel in it—the perfect man in the Age of #MeToo.

Backed by hard work—who can top a prep of ten months, training with rappers Divine and Naezy for 2019’s Gully Boy?— Ranveer’s star seems set to ascend higher, even in an increasingly crowded sky where a new star boy is born every year. Yet there is the lurking anxiety of more discerning audiences learning to distinguish between a star and an influencer.

Also Read: The Khans just can’t do what Diljit Dosanjh did. Stop singling out Muslim celebrities

Then there is Everyman Khurrana, who has become a past master at negotiating the complexities of what it means to be an ordinary man in the extraordinarily complex India of today, with its deep social divisions, increasingly independent women, harsh economic realities and traditional systems of managing conflict. With an ease born of five years of travelling to different college festivals with his two theatre groups, meeting a variety of people, and working in radio and TV as a presenter, Khurrana finds himself uniquely placed to embody the fluid masculinity demanded of the once invincible Hindi film hero. Alpha Male, move over: meet the Alphabet Male, reconstructing himself bit by bit, letter by letter.

Nowhere did he portray this flawed, vulnerable, not-a-hero better than in his fourth film, Dum Laga Ke Haisha (2015), which saved his career from spiralling into a freefall after a successful debut in 2012, in Vicky Donor. ‘Krantikari banenge. Makkhi toh maari na sake hai inse,’ (They want to be revolutionaries, but they can’t even kill a fly), says the father of the character played by Khurrana in Dum Laga Ke Haisha. The father is talking of an organisation suspiciously like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) which instructs boys on how to be men and whom to follow as role models—Bhagat Singh, Subhas Chandra Bose, Shivaji and Atal Bihari Vajpayee. It’s a confusing list. It has a communist, a lapsed Congressman, a Maratha warlord and a poet-prime minister under whom India triggered its second series of nuclear tests.

It’s the kind of masculinity Indian men grow up with, in the shadow of their fathers’ expectations, usually coddled by overprotective mothers and taught by society to feel entitled. Listen again to Khurrana’s father, Chandrabhan Tiwari, played by Sanjai Mishra: ‘Dasvin toh nikaal nahin paaya, Juhi Chawla ke sapne dekh raha hai.’ (He couldn’t clear Class X and he’s dreaming of Juhi Chawla.) The film is set in the ‘90s, the heroine (played by Bhumi Pednekar) is better educated than he is, and yet he believes he can do better than her in life and is superior to her.

Between the toxic man best exemplified by Salman Khan in his portrayals of men who are tone-deaf to women and most recently reprised by Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, and the nationalistic man whose heart beats only for India, epitomised by Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgan, Khurrana has opened the gates for male actors such as Rajkummar Rao and Vikrant Massey, who are also willing to try out new personas. Whether Khurrana is a young man embarrassed by his inability to perform in bed in Shubh Mangal Saavdhan (2017), a writer unsure of winning the woman of his dreams in Bareilly Ki Barfi (2017), an adman facing the prospect of his middle-aged parents having a baby in Badhaai Ho! (2018), or a store-keeper who is obsessed with staying on in a crumbling haveli in Lucknow and is routinely insulted by his better educated sister and lover in Gulabo Sitabo (2020), this actor symbolises the man in the middle, torn between a patriarchal upbringing and a rapidly transforming society.

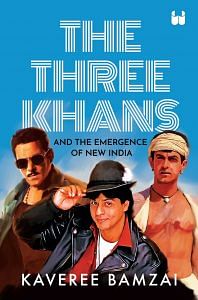

This excerpt from ‘The Three Khans: And the Emergence of New India’ by Kaveree Bamzai has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Three Khans: And the Emergence of New India’ by Kaveree Bamzai has been published with permission from Westland Books.