India’s neo-liberal shift coincided with the emergence of a right-wing Hindu extremist political movement. It is no coincidence that these two forces intersected the way they did. Neo-liberal reforms dislocated millions of youngsters from life in rural India and transplanted them to increasingly crowded urban centers where, often jobless and struggling to survive alone, without the comforts of the village and necessary support structures, they were ripe for the plucking by fundamentalist forces such as the hardline Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP was formed in 1980 as the political wing of the fascist-inspired, paramilitary Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). By the mid-1990s, through an agitational campaign the BJP was transformed from a fringe party to one that secured approximately 40 percent of India’s “very high-class” voters. No other Indian party, according to election data for 1999, captured such a high percentage of that electorate class. Additionally, these upper-class voters were the only economic segment that voted so enthusiastically for the BJP.

Right-wing nationalism found a natural base in the NRI community. No longer were they abandoners of the motherland, but enterprising, hardworking vanguards, uplifting Indianness through their individual success and accomplishments. NRIs were too distant to bear the consequences of living under BJP rule and so were perfect allies; in addition, they had no political responsibilities. India does not allow dual citizenship, and any NRI who becomes a passport holder of another country can no longer vote or participate in the political system. They could only give back to the state through remittances, donations, and an insecurity over their own cultural loss, which made them receptive to the BJP’s chauvinistic nationalism. Furthermore, in their adopted countries, NRIs rarely had power matching their material prosperity—a fact that enraged many enough to drive them back to their homelands where they attempted to wield power by proxy.

Also read: Fauji: The show that launched a broody, chain-smoking SRK on the path to Bollywood glory

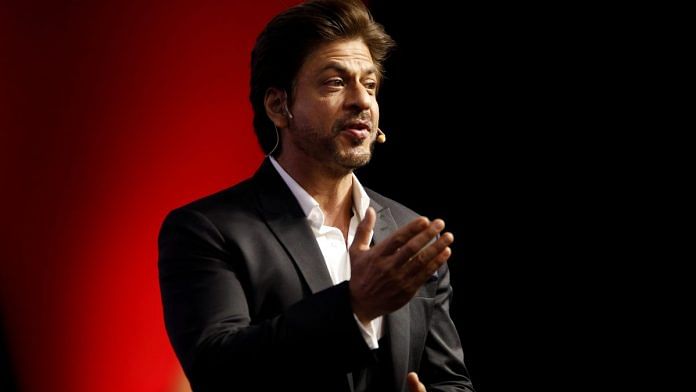

It is precisely at this moment of India’s breakneck liberalization, when the country’s secular foundations were seismically challenged, that three stars appeared on cinema screens: Aamir Khan in 1988’s Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, Salman Khan in 1989’s Maine Pyar Kiya and Shah Rukh Khan in 1992’s Deewana. The three Khans—none of whom are related—were all born in 1965. At the time of their Bollywood breakout they were all in their early twenties. Aamir and Salman had influential fathers in the movie business, Shah Rukh did not. They were all educated, English-speaking, from comfortable if not well-off backgrounds, clean-cut, and, interestingly, the three biggest actors in India all came from a minority community that made up less than 15 percent of the population: They were all Muslim.

The fact that the three Khans all rose in stardom at the same time is meaningful in the Indian and subcontinental context. In their earliest manifestations, the three Khans represented three prevailing spiritual and political ideas of India and the subcontinent. In this, Salman Khan’s film persona was initially built on a defiant masculinity and a determined Muslim identity—though he may do love stories, you won’t catch Salman being pushed around by a love interest. In Nizamuddin, the historic Muslim area of Delhi, it is Salman’s face on the T-shirts of young men, not Aamir’s or Shah Rukh’s. Even as his politics, or lack of them, in real life is increasingly marked by timidity, in his heyday Salman Khan starred in films set on the Indian-Pakistani border where he takes in a Pakistani orphan and most audaciously plays an Indian RAW (or Research and Analysis Wing, India’s intelligence agency) agent who falls in love with a Pakistani beauty who happens to spy for the ISI (or Inter-Service Intelligence, RAW’s Pakistani counterpart).

Aamir Khan is widely considered to be the intellectual of the three Khans and his films are lauded as probing and artistic. They also happen to be massive blockbusters. His 2016 film Dangal is the fifth most successful non-English film of all time and was a phenomenal hit from China to France. Aamir could be said to stand on the other end of the spectrum from Salman. He is Muslim, but never overtly so. Rather, he surrenders to the presiding energy and moment, largely accepting if not the values of the status quo, their dominance. Though in his personal life Aamir has criticized India’s rising intolerance (while at the same time engaging in numerous Prime Ministerial photo-ops), in his films he doesn’t engage in that fight. Aamir’s films pointedly won’t touch the politics of the time, but will focus on benign topics like dyslexia, general tolerance among mankind or women in sports.

Also read: Bollywood’s Royals: Brave heroes on screen, spineless zeroes off it

While Aamir and Salman played heartthrobs in their first starring roles, Shah Rukh starred as homicidal maniacs and obsessive stalkers in three of his early movies, all blockbusters. In Baazigar, he asks a girl to marry him, makes her write a suicide note as a test of her love, and then pushes her off a building. After she dies, he adopts a new name, promptly asks her sister out, and ends the film by murdering her father. In Deewana he plays an awkward anti-hero romancing a woman whom we think is a widow, but…and in Darr—“A violent love story” is the film’s tag line—Khan plays a deranged, stuttering stalker. In the film he terrifies his love interest by calling her on the phone constantly (“I love you, K-K-K-Kiran”), breaking into her house, and shooting and stabbing her husband. Surprisingly, Indian audiences rooted for Khan’s psychopathic character, not his frightened victim, enthusiastically cheering him all the way. “Pop sociologists,” Pankaj Mishra noted, attributed Darr’s success “to the growing ‘anomie’ in Indian society.”

It is as though Khan’s characters understood something other heroes didn’t: this new world order accommodated, if not rewarded, violent confrontation. What mattered now was the hustle, how fast you rose, and how hard you fought your competitors. India had changed, and with it, the rules of the game in Bollywood. “He can die in the film and lose the girl,” Khan later said of his creepy character trifecta. “He can kill people. We don’t have to like him, just the story he is telling.”

Also read: Shah Rukh, Aamir and Salman now starring in ‘Silence of the Khans’ under Modi rule

Of all his contemporaries, Shah Rukh Khan’s early life and career had been built on the old Nehruvian idea of India— pluralism, brotherhood and symbiosis between its two biggest religions, Hinduism and Islam. Khan is Muslim while his wife, Gauri, is Hindu. His family came from Peshawar, Pakistan, but his father fought for India in 1947. His youngest son, born through surrogacy, is named AbRam, a combination of Abraham, a Muslim prophet, and Ram, a Hindu god.

Straddling both India’s ways of being, today Khan is a lonely figure. In his films, he was the bridge between socialist India as it moved toward its hyper-capitalistic future, and a guide to how one could be modern but still principled and traditional in neo-liberal India.

This excerpt from New Kings of The World: The Rise and Rise of Eastern Pop Culture by Fatima Bhutto has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from New Kings of The World: The Rise and Rise of Eastern Pop Culture by Fatima Bhutto has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

FATIMA BHUTTO related to Fake surname user THE PRINT using skull cap writer to satisfy insulting HINDUS

what a rubbish article….not leading anywhere except nudging us to read/buy the book. Can ThePrint stop wasting space for excerpts that dont mean much when taken out of their context and pls clearly inform/warn the reader upfront if the article is nothing more than a book excerpt.

Abraham was jew, you guys make every middle east one as muslim

The print must not give space to Anti-Hindu pakistani muslim writers like Fatima bhutto, shameless print.