Eventually I put some ghosts to rest.

I had decided my pilgrimage to Peshawar would include three places: the house where my grandfather, my mother, Didi and I were born, my school, and the famed Balo-ji ka Ghantaghar.

Peshawar is a valley located in one of the most beautiful parts of the world—in the ancient land of Gandhara and its surroundings. It is a lush location, surrounded by mountains, irrigation canals, rivers and, of course, flowers. There are no such places in the world.

I was travelling to Peshawar after fifty-three years. As we entered I could see the crowded city it had become and yet, I still found the beauty I remembered. There were flowers everywhere, in the traffic islands and the dividers, and lining the routes mustard flowers shown like fields of gold. I could understand why Peshawar’s ancient name was Pushpapura, meaning the city of flowers.

Yet, that day my eyes searched not for this natural beauty but for traces of my past. All I saw was a crowded city that I did not recognise. Nothing felt familiar.

Partition had taken place over half a century ago, we had been given house and land in India, I had lived a full life and now called Delhi home. Yet, I had left a life behind, my family had left their lives behind and that would never be settled. Why should roots matter?

Perhaps it is not so much the question of roots as being chopped off from the original tree and having to scrabble to survive elsewhere. Perhaps where we are born is stamped into our genes.

What do you say about the people who came from Peshawar but are now in India? What is their identity? There is no identity left of the people who came because of the partition. I’m a member of small societies, small groups on Facebook about Peshawar, where we meet and talk about Peshawar. Outside of that, what identity do we have? Who knows Peshawar? When I went to renew my passport, the passport officer didn’t know where to put my place of birth, since it was Peshawar, but it was not in India now.

I went to meet the Regional Passport Officer, a young and smart Sardar. He solved it by creating a column that said ‘Undivided India’. He said, ‘There are very few people like you left.’ It was true. It’s also true that in another ten or fifteen years, there will be no one left. And with the people will go the histories. Everything will be forgotten, and who will be interested in this little story?

But I was alive and I was in Peshawar and I had traced my family back to six ancestors in Peshawar and found only one concrete proud survivor, the clock tower. It was built by my great grandfather, Lala Balmakand Sahib, in 1900, who gifted it to Queen Victoria for her Diamond Jubilee—a fact mentioned in most travel books about Pakistan.

I was carrying one myself—Footprints by Dave Winter and Ivan Mannheim. Seeing his name in print was like a magnetic pull, or a password to my missing past.

I had to see it, I had to touch it, and say farewell.

The fabled house of my childhood dreams was there, and yet not there. When we reached Peshawar, I didn’t know my house address, but I had a vague idea that it was near Hashtnagari Darwaza (Hasht means eight and Nagar is village; a road goes towards the famous Hashtnagar area from there, hence the name). I knew that there was a hospital nearby, also built by my grandmother, and a masjid adjoining our house.

We passed these landmarks, I saw the masjid, and there was what might have been a haveli beside it. But the façade of the house had totally changed. I couldn’t recognise it. I called an aunt and asked her for the house number. But so many years had passed that nobody could remember it. Yet when we stopped there, I knew this was it. I could make out the railings and the façade, but the terrace and its parapets were missing, and the regal front entrance was not there.

We entered the building. A sign proclaimed this was Khan Klub. We went in.

I told the people of Khan Klub that I had been born there, this had been my house. My voice broke. Tears flowed from my eyes.

The people at Khan Klub were kind and cried with me.

They brought their senior owner. He patted me on the head and comforted me.

When I had calmed down a little, he told me the tale of the house and the hands it had changed over the years. Three brothers had been allotted the house, and over time they had divided it.

One portion had been razed to the ground, in the middle there was a shopping mall, and one remaining bit of the house had been restored and was Khan Klub.

The owner told me to look through Khan Klub to my heart’s content. The first place I went to was my mother’s room. I climbed up and I thought I would come to Mummy’s door, but it was all changed—the large room of my memory, even its doors were not there now.

The original haveli had a hundred rooms; this remnant had forty. They had been further redesigned and re-apportioned. Large rooms had been divided into many smaller ones. I couldn’t connect to the one where I was born.

Yet, the mosque beside the house was there and the downstairs area looked like I remembered, but it was different.

The owner wouldn’t let us go till we had lunch. Tiptip, Lotun, my hostess Meeta, Anwari and I sat down to eat. I don’t remember what we ate. Perhaps it was kebabs, but I was lost between the past and the present, between disappointment and joy. I must have spoken but I know not what. Our hosts refused to take any money from us. No money was exchanged that day. Only emotions were.

Later, I joined groups that talked about Peshawar’s history and learnt from Peshawar-based historian Dr Ali Jan that Jemima Khan and Imran Khan had stayed there and that it had been the base of most foreign journalists during the Afghanistan war.

The war might have been over on paper and 9/11 was yet to take place but the city was still full of foreign journalists, many of whom were going to the frontlines and then retreating to the safety of Peshawar to bathe, rest and eat.

From the haveli, we went up to the Khyber Pass, no man’s land. We passed Jamrud Fort, constructed in 1836 by Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s general Hari Singh Nalwa, who was the commander of the Sikh Khalsa Army. It reminded me that swathes of Sikh heritage and monuments are littered through the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa area and that the Jamrud Fort was originally called Fatehgarh, to celebrate the Sikh victory over the tribes of the area and the expansion of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire beyond the Indus and right up to the Khyber Pass, establishing Sikh rule in Peshawar. How much of my Sikh heritage would I never know?

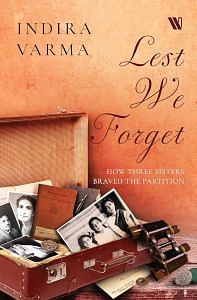

This excerpt from Indira Varma’s Lest We Forget has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from Indira Varma’s Lest We Forget has been published with permission from Westland Books.