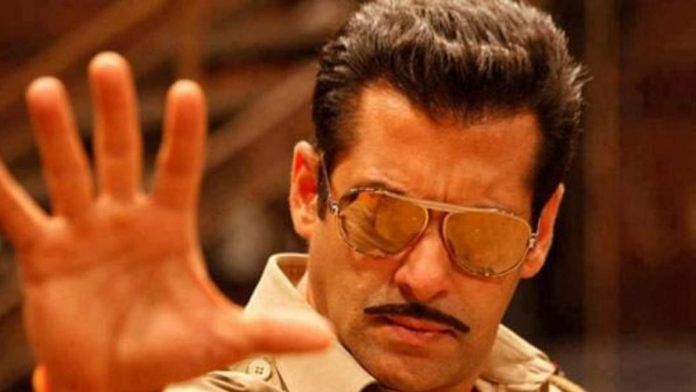

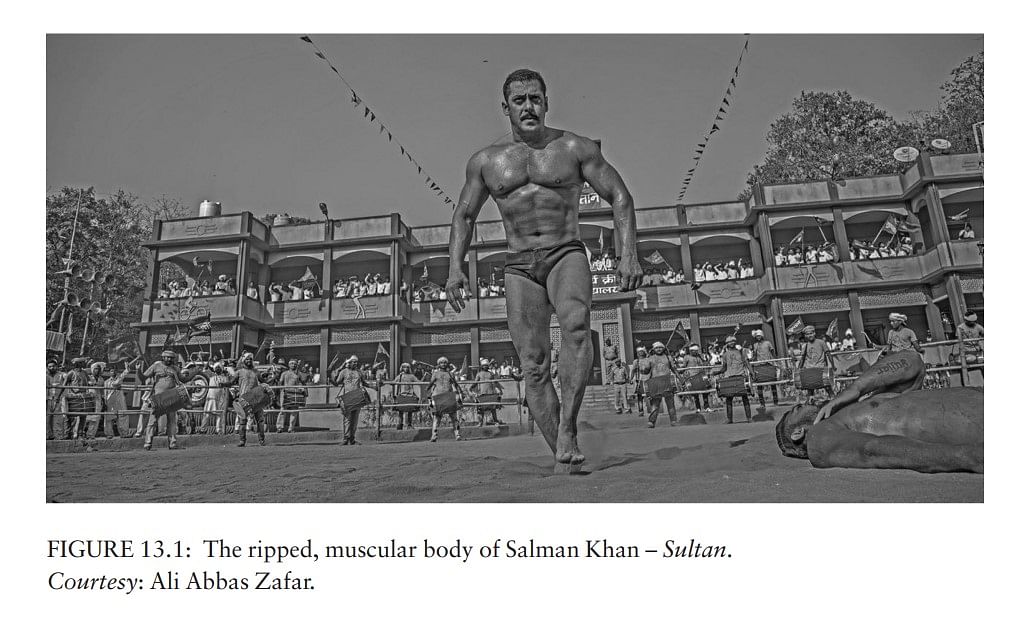

Salman Khan is one of the most- discussed but least-studied stars of Bombay cinema. When Martin Shingler recommends expanding the scope of studying Bollywood stars, he provides a wish list of top stars, including Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan, but Salman is conspicuous by his absence (2012: 182). Despite his staggering box-office success and formidable fan base, Salman Khan’s films have been subject to academic indifference, if not disdain. Salman Khan is arguably Bollywood’s most controversial star. To admit to being a fan of Salman is to elicit astonishment and disbelief. While the star, along with Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan, has been part of Bollywood’s ruling triumvirate exerting tremendous command over the box office and their expansive fan bases, it is commonly assumed that Salman-starrers cater primarily to the ‘substratum of the urban lumpen and working-class male audiences’, pejoratively described as the ‘lowest common denominator’ (Sen and Basu 2013: 12). The ripped, muscular body of Salman – an object of much veneration by his fans – is confirmation for many that his star appeal has more to do with brawn than brain (Figure 13.1). ‘The ridicule directed at body building’, observes Yvonne Tasker, ‘stems in part from the ambiguous status of the musculature in question’; for some critics, muscles are merely ‘non-functional decoration’ (2002: 78). The locus of deep ambiguities, the star text of Salman Khan is created as much by his on-screen performances as his off-screen reputation.

Also Read: ‘Tiger is always ready’: Salman Khan tells Katrina Kaif as they announce release date of ‘Tiger 3’

The annals of cyberspace are replete with stories about his fits of violence, unpredictable mood swings and criminal cases for drunken driving and poaching endangered animals. Notwithstanding the dark side of Salman Khan, the star’s box-office saleability and devoted fan base remains unshakeable. Exercising a ‘bad object choice’ to study Bombay cinema’s enfant terrible, this chapter explores the star’s early success in the B and C centres of film distribution and his tremendous popularity among particular constituencies of the subaltern viewer. It pays special attention to the working-class Muslim with whom the star has enjoyed a special affiliation.

The rise of Salman Khan

Starting his career as a romantic hero in Maine Pyar Kiya (‘I have fallen in love’, dir. Sooraj Barjatya, 1989), Salman Khan’s rise to superstardom was accompanied by as many hits as flops. While his romantic comedies, including Andaz Apna Apna (‘A style of one’s own’, 1994), Pyar Kiya to Darna Kya (‘Don’t be afraid to love’, 1998), Judwaa (‘The twin’, 1997), Biwi No. 1 (‘Wife no. 1’, 1999), No Entry (2005), Mujhse Shaadi Karogi (‘Will you marry me?’, 2004), Maine Pyar Kyun Kiya (‘Why did I ever fall in love?’, 2005) and Partner (2007), added substantially to his success at the box office, his stature was consolidated by action films that explore the shadowy underside of the urban experience where ethical boundaries have collapsed and the protagonist occupies the liminal space between legality and criminality.

In 2009, Salman Khan’s career took a sharp upward swing with the blockbuster Wanted (dir. Prabhu Deva), followed by the stupendous success of Dabangg (‘The fearless’, dir. Abhinav Kashyap, 2010), a film that converted a large section of the more elite multiplex audience into Salman fans. Outlook reported:

‘Despite his unquestionable star appeal, box-office clout and exclusive membership of the Khan trinity, Salman has been largely side-lined as the B and C centre hero, the one loved by the masses and inconsequential for the classes. But the resounding success of Dabanng changed everything. An action-comedy set in the rural badlands, Dabanng was not only a sensation in Salman Khan’s traditional fan base but also captured the imagination of the urban middle classes who were prone to deride Salman-starrers as lacking ‘class’ and ‘taste’.’ (Joshi 2010: n.pag.)

In an interview to Tehelka Magazine, Salman described Dabangg as a ‘sten-gun assault on the polite multiplex crowd’ who he hoped would ‘whistle and dance on the chairs’ which is precisely what they did (Chaudhary 2010). Reeling under the shock of Dabangg’s success, national weeklies like Outlook, India Today, Tehelka and Brunch carried, for the first time, cover stories on the star. The success of these two films were followed by Bodyguard (dir. Siddique, 2011), Dabangg 2 (‘The return of the fearless’, dir. Arbaaz Khan, 2012) and Ek Tha Tiger (‘Once, there was a tiger’, dir. Kabir Khan, 2013), each of which crossed the 100- crore mark. Made with a budget of 80 crores and shot over several international locations, Ek Tha Tiger swept both Salman- strongholds and multiplex audiences making net domestic collections of nearly Rs 200 crores and over 300 crores worldwide. At the time of its release, it was Salman’s most expensive and profitable film. The following year, Kick earned 165 crores in the first week and over 300 crores by the end of the fourth week. With an estimated annual income of 244 crores, Salman Khan became Bollywood’s most saleable star and the undisputed hero of both the ‘masses’ and the ‘classes’ (Lall 2015).

Also Read: SRK, Salman, Kohli… Unlike Ronaldo, Indian celebs have endorsed junk food for years

How is Salman Khan’s stardom distinct from that of Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan? Unlike the two, Salman Khan, till much later in his career, seldom worked with top directors or big banners. Through his films and countless endorsements for high-end products, Shah Rukh has been a lifestyle icon for upward mobility and a self-made success. His biographer Anupama Chopra writes:

‘A leading monitoring firm called the Agency Source (TAS) tabulated that between 1994 and 2006, Shahrukh appeared in 281 print ads and 172 television commercials. In 2005 alone, he endorsed approximately 34 different products. Shahrukh was the ubiquitous symbol and conduit for the new consumerist society.’ (2007: 160)

Like Shah Rukh, Aamir Khan was also a highly paid endorser of brand names who, with the success of the TV show Satyamev Jayate (‘The truth will prevail’) consolidated his position as an inspirational brand ambassador for corporate social responsibility. While Shah Rukh and Aamir have been the icons for a globally mobile generation in post-liberalization India, Salman’s stardom is located along the underbelly of the very landscape over which they reign. Designated ‘king of the single-screen’, Salman Khan’s traditional fan base was located in provincial towns, suburban areas, urban slums and mohallas.

This excerpt is taken from the essay titled ‘Transfigurations of the Star Body: Salman Khan and the Spectral Muslim’ by Shohini Ghosh in ‘Bombay Cinema’s Islamicate Histories’ by Ira Bhaskar and Richard Allen. It has been published with permission from Orient BlackSwan.