There are three bastions of democratic constitutionalism in Asia: India, Japan, and Australia / New Zealand. Each system is anchored in many decades of successful practice, and large consequences would follow if these countries fail to reinvigorate their twentieth-century legacies. Such setbacks would not only cast a shadow on more recent constitution-building efforts in the region. Major failures will have world historical significance, given Asia’s rise to world power in the twenty-first century.

Asia, like Europe, is a place of many paradigms. India’s constitution is revolutionary; Japan’s is an elite construction. Australia and New Zealand have adapted establishmentarian traditions inherited from Westminster. It would be a mistake to launch our investigation with loose talk about “Asian constitutionalism.” The subject is best approached by considering each major regime as an exemplar of its respective ideal type.

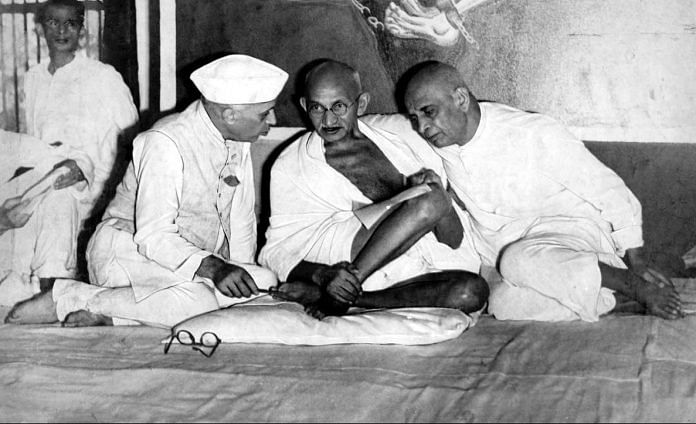

Given my concern with revolutionary constitutionalism, I will focus here on India and defer other Asian regimes to later volumes. India’s experience provides a particularly useful starting point, since it permits a multigenerational perspective on the four-stage dynamic characteristic of this ideal type. We begin at Time One, with Gandhi and Nehru transforming the Congress Party (known simply as Congress) into a mass movement during the first half of the twentieth century—and then turn to the Time Two effort to constitutionalize Congress’s revolutionary politics at the Founding, and then move to the bitter succession crises of Time Three and finally to the Supreme Court’s effort at Time Four to establish itself as the leading defender of the constitutional principles left behind by the revolutionaryConstitution established by the Founders.

Also read: India’s Constitution makers Nehru, Patel & Ambedkar were divided on parliamentary system

This century-long history will serve as a reference point throughout this book, but it will be particularly useful in our second case study: South Africa. There are some striking similarities between the African National Congress and its Indian counterpart. Yet the two national liberation movements take different shapes during their periods of insurgency—partly because of the very different ways in which the British and Afrikaner regimes confronted emerging revolutionary threats.

Speaking broadly, governments respond to insurgencies by mixing two strategies: coercion and cooptation. But the mixes can be very different. The British frequently used force in India, but they also tried to tame Congress by offering it a secondary role in imperial government. Gandhi initially resisted these offers, but Congress under Nehru accepted the British invitation and vigorously participated in elections for consultative assemblies set up by the Raj. This not only required Congress to engage in the hard political work involved in organizing a movement party. The party’s victories at the polls allowed its leaders to use the colonial assemblies as platforms for legitimating their claims to speak for the People.

South Africa’s apartheid regime was much more brutal. It launched an intensive military effort to crush the ANC. This made it impossible for the insurgents to establish a well-organized movement party of the Indian type. Instead, Afrikaner suppression split the ANC’s leadership in two. Nelson Mandela and his fellow revolutionaries were thrown into captivity on Robben Island, while Oliver Tambo pieced together an ANC-in-exile out of very disparate movements. At the same time, ANC sympathisers at home were driven underground, and lacked the capacity to coordinate their local efforts with fellow activists in other cities and regions.

Along with its continuing campaign of suppression, South Africa’s governing National Party did make intermittent efforts at cooptation. But its heavy reliance on brute force undermined the trust necessary for the ANC to take these gestures seriously. Instead, the regime’s systematic violence provoked the ANC to sponsor a formidable guerilla army, the Spear of the Nation—which the ANC’s civilian leadership had difficulty controlling.

These different patterns of movement development in India and South Africa made a big difference at Time Two—when the two revolutionary movements hammered out constitutions in the name of the People. Nelson Mandela confronted problems in gaining the backing of his fragmented supporters on a scale that Nehru and his allies did not encounter. Mandela’s response to this “coordination problem” will set the stage for an analysis of analogous problems raised by similar splits in later case studies.

Also read: India’s founders gave us our Constitution. We must prove to them that we can keep it

The Indian case provides a second orienting perspective. South Africa’s experiment in constitutional democracy has now lasted a quarter century.

While all presidents of the revolutionary Republic played significant roles in the liberation struggle, none possessed Mandela’s charismatic centrality. His departure from office has led to a series of succession crises as leading con- tenders competed for ascendancy.

This was also true in India—which experienced a particularly explosive crisis. While South Africa’s transition to Time Three remains in doubt, India’s much longer history permits us to see how it managed to resolve its dilemma in a way that enabled the Supreme Court, and other independent institutions, to establish themselves as the preeminent defenders of the nation’s revolutionary legacy.

This excerpt from Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of Law by Bruce Ackerman has been published with permission from The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

This excerpt from Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of Law by Bruce Ackerman has been published with permission from The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Revolutionary or Revulsive constitution….. As in comments before, the Equality has been killed by ordinance…..

It has been a copy of British !

As mentioned coercion and co-opting…. M.K. Gandhi was a planted Stooge of British who criticized the Africans ! The real victory of Independence was due to Revolutionary armed struggle…. Congress created charismatic Unity and this was to be disbanded later as per Gandhi and rest is History (mostly British)….. As for South Africa Mandela and Winnie were poles apart…. She being among the rooted Local population !

India’s Constitution was revolutionary for the time in which it was drafted. However, numerous constitutional amendments have gone against the principles on which the Indian Constitution was written. For instance, the addition of the words “secular” and “socialist” by the Indira Gandhi led government during the Emergency was totally unnecessary. India was never thought of as a socialist republic when the Constitution was drafted. Yes, India has largely been a secular country so far, but there must be some good reason why the founding fathers didn’t think it necessary to have the word “secular” added in the preamble.

Why parties are scared of removing this fake socialism and even more fake secularism?

Revolutionary constitution? Ok, i mistook it for third class two penny Socialist constitution. Or revolutionary third class two penny constitution is apt perhaps