In May 2022, Rahul Gandhi went to Cambridge after participating in the ‘Ideas of India’ event, in London, to mark seventy-five years of India’s independence. He carried along with him his ‘union of states’ argument from February. For two very different opening questions at these two venues, he began with the same answer about India being a ‘union of states’ and not exactly a ‘nation’, which he called a European idea. Rahul should have realized long back that the answer to this classical debate—if we existed as an emotional and civilizational whole, long before we became a sovereign republic in 1950 —was not in historical details but in feeling and sentiment. The antiquity of civilizational India or Bharat has been emphasized in these debates. And the political right always approaches this through culture and religion.

Rahul Gandhi made some very confusing remarks in London and Cambridge, which no pragmatic politician will ever bring to his lips. He said the nation did not exist till the constitution loosely bound it as a ‘union of states’. He also said that India was a ‘top-down’ idea and did not emerge as a ‘bottom-up’ idea. By saying this, he had put to doubt the freedom movement that his own party had led to integrate India. The freedom movement was all about emotionally knitting civilizational, subcontinental commonalities, and accommodating differences and diversity as mere cultural scripts of a universal idea. One of the simplest exercises of M.K. Gandhi to communicate this civilizational commonality despite the various scripts was to sign his name in all major Indian languages and create Pradesh Congress committees on linguistic lines.

The ‘soul’ of India that Nehru spoke about, and which Rahul Gandhi referred to in his interactions, also stems not from constitutional history but from civilizational history. The question really is: should Rahul as a political leader embrace hair-splitting legalese instead of a collective idiom that helps connect his party to the multitudes? In his interactions, he seemed to have confused the federal idea with the existential idea of India. The federal idea does exist and is important, but the existential idea governs the federal idea. Even the Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu stopped speaking with a seditious intent in the mid-1960s. But still, a party like the DMK foregrounds federalism and the ‘union of states’ argument that is perfectly valid. But, for a Congress party to make the same argument is self-defeating.

By speaking thus, Rahul has questioned the assumed national character of his own party—a party that created purpose for the diverse cultural scripts in the subcontinent. Even a shoddy sycophantic slogan of the Congress party in the 1970s—‘India is Indira and Indira is India’—only tried to consolidate the national footprint of the party, which Rahul Gandhi did not seem to be very concerned about when he spoke about ‘union of states’ that does not exactly build emotional linkages for him or his party. Rahul did not seem to have thought through the cultural questions, and when he is confronted with them, he offers shorthand technocratic or economic answers. He also appears to confuse the cultural for the spiritual. Cultural is political too and that is what the Sangh Parivar has proved and continues to prove every single day. Rahul Gandhi cannot be a lotus eater sidestepping this reality totally.

The word ‘negotiation’, which was repeated in Rahul Gandhi’s utterances during the interaction in London and Cambridge, proved again that he is more comfortable with a legal and economic resonance instead of a cultural ring to his words and phrases. He does not realize that he disconnects with the audience the moment he tries to be a lawyer instead of a politician. That is why he went speechless for long seconds in Cambridge when he was asked about his father’s assassination. It looked like he was struggling for words. That may be a sign of deep unhealed wounds and the integrity of his person that does not feign, but sadly, he was on a political platform and his father’s assassination was a political act.

The Sri Lankan question was about cultural autonomy and his father had not understood that. By speaking about the ‘union of states’, Rahul Gandhi has technically gone beyond his father, but by culturally approaching it, he could have reduced the tentativeness in his voice. H.Y. Sharada Prasad, who served Indira Gandhi as information advisor for her entire term in office, recounts in his book of essays, how Rahul Gandhi’s grandmother prepared for public performances, more particularly press conferences.

He says: [Indira Gandhi] expected her staff to give her, five or six days in advance, a list of questions that the press was likely to ask, couched in the toughest possible manner. Apart from studying the questions, she held regular rehearsal to which some senior officials like the foreign secretary, the finance secretary and the home secretary were called besides officers of their own secretariat. The dummy press conference went on for an hour-and-half or two. On some of the most knotty issues, she also called for further written notes. In the same essay, commenting on Nehru, Sharada Prasad says, he ‘seemed to treat press conferences as seminars’. About Rajiv Gandhi, under whom he served as information advisor, he says: ‘[He] was more than affable. But the press conference for which he is remembered is the one where he abruptly announced the dismissal of a foreign secretary. It came so sudden that the assembly could not even gasp.’

It is very tempting to assess Rahul using his own family elders as a measure. It is not an unfair exercise because dynastic politics invariably creates such comparisons. Rahul certainly does not possess the gift of a Nehru to convert every public interaction into a philosopher’s profundity and a historian’s broad sweep. But he may have inherited Nehru’s penchant for a monologue. The diligence and preparation of Indira Gandhi may be missing in the grandson because there is a casualness and abruptness in all that Rahul speaks in public.

He has strong opinions, and often force-fits them into any question that is posed to him by an interviewer or a journalist. Nehru’s brooding, or reflection, or seizing an insight as it comes while speaking is not what he does. Indira Gandhi’s preparation and practise made her feel a natural. Her spontaneity quotient was less than that of her father, but both drew from a deep well of lived social and cultural experience which shaped their words both scripted and unscripted. Rahul, like his father Rajiv Gandhi, has little to draw from experience that concerns the Indian collective.

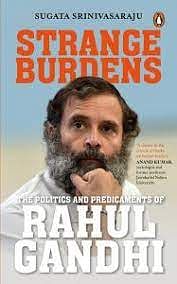

This excerpt from Sugata Srinivasaraju’s ‘Strange Burdens: The Politics and Predicaments of Rahul Gandhi’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Sugata Srinivasaraju’s ‘Strange Burdens: The Politics and Predicaments of Rahul Gandhi’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.