That weekend, my in-laws visited us. We were having our evening tea, sitting on the carpet, when the doorbell rang. I got up to answer it. Alyque Padamsee stood on the landing, in the gloaming. Magic hour, they call it.

‘We went to see a movie,’ he whispered. ‘At Regal. Pearl is buying tickets. And I said I’ll park the car.’ He paused and looked at me. ‘But I had to see your face. I have to go now. Pearl will be waiting. I only came to see your face.’

And he was gone.

Who does that? Drive from Colaba to Pedder Road to see your face for an instant and then drive back to his wife?

That was the moment I fell in love with him. There was no line left to cross – I was his, body and soul. I returned to my in-laws and my husband and took my place on the carpet. I was calm, not too nervous. I hoped my face didn’t give me away.

Inside, I was smiling. I was euphoric. I have never forgotten that feeling.

I was on a two-month sabbatical from work. Shivendra Sinha, my friend from London, was making a film and I was helping him, which meant my days were all my own. Dilip only returned home after 7 p.m.

The very next afternoon, the doorbell rang again. Alyque stood there. He’d stolen away on his lunch break. I let him into the flat. It was the 30th of November 1970.

Surely he can hear my heart, I thought. It’s much too loud. We faced each other. We didn’t say much. Talking was done. I remember him. I remember his touch.

We made love. For the first time. This was not sex, I remember thinking. Nothing that made me feel this way, whatever this was, something that made me feel this special, so good and so right, simultaneously brand-new and familiar, all at once – the term sex couldn’t contain this. He was gentle and kind. Calm and considerate and absolute.

It was the sensation of an endless fall, with no fear of what waited after. I was now an adulterer and a mistress, and I could have died there, in his arms, no questions asked.

For a while, we fooled everyone. Including – of course – ourselves. Once I was back at work, the Open Marriage Contract between Dilip [Thakore] and myself was in my favour for a change. We had no rights over each other, Dilip and I.

I began to have a lot of ‘recordings’ at 7 in the morning. Alyque would pick me up across the road and, we’d drive to a shack in Juhu for breakfast, at the Palm Beach Hotel (which is now the Ramada Inn). I’d be at work by 9.30.

I don’t think we’d have made it in this day and age, Alyque and myself. Traffic wouldn’t have allowed it. Had he tried the parking stunt now, it would’ve taken him an hour and a half.

The clandestine breakfasts must’ve really cost Alyque. He was never a morning person.

I started to spend a lot of my weekends ‘with Esmie’, in ‘Bandra’. Alyque would pick me up, and we’d drive to the picnic cottages in Versova. Sometimes, we checked into a room at the seedy Hotel Ajanta in Santa Cruz. We were lucky. This was a time before television and no one recognized us.

Our trysts were rushed and sordid and necessary. They were blissful.

The world, now soft-focus, passed by me in a blur. Even Dilip, reliably caustic, had receded to middle-ground. I was a secret society of one, and I was in love. People have survived on less.

We stumbled on, in a daze of lust and guilt and joy, for about eight months.

Also read: Alyque Padamsee, the ad genius who kept advertisements simple and direct

We inched towards an anniversary, of sorts. Dilip was at the High Court until 7 in the evening. He and I had settled into a strange mixture of contempt and concern. Strangely, things between us were less volatile than even a year ago. Mostly, we ignored each other, especially if we were out. Every conversation revolved around separation and divorce. We had drifted so far away from each other that it didn’t matter.

One evening, in late 1971, Alyque told me he’d been living out of a suitcase at Kulsum Terrace, the family home in Colaba, for weeks. Sylvester da Cunha had seen the two of us together, and Alyque had been given an ultimatum. He’d decided to move out. But the onus was on me.

It didn’t take a lot for me to agree to Dilip’s proposal for a separation. On the 1st of December 1971, two-and-a-half years after we’d got married, he moved to Buckley Court. I helped him pack, and I drove him to his temporary digs.

I called Dilip’s father before we made the final decision. I wanted his blessing. I wished to keep ‘Thakore’ as my last name. It was my professional name in Bombay now. And it seemed safer, more Indian, less Christian. It made absolute sense, and I hated myself a little.

Pappa said ‘yes’.

Also read: India bans condom ads because 50-year-olds still can’t deal with 15-year-olds having sex

Here’s an interesting thing about the times we lived in, back then, so very different from the more enlightened times we live in now. In the initial few months after Alyque and I went public, I was shunned. But Alyque wasn’t.

I wonder if gender had something to do with it.

Surely not?

A fabled union had unravelled. At its heart was a storied romance.

Alyque had been in love with Pearl since college. And had waited almost a decade to marry her.

I’d broken up a family. There were kids. And I had a husband. Well, sort of. I was the ‘other woman’.

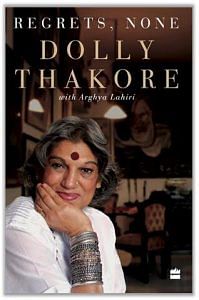

Dolly Thakore is a veteran actor, newscaster, columnist and casting director who has worked in advertising, communications and public relations.

Arghya Lahiri is a writer, theatre director, lighting designer and filmmaker.

This excerpt from Dolly Thakore’s ‘Regrets, None’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Dolly Thakore’s ‘Regrets, None’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.