I think my mom never expected to have to have The Talk in America. My parents’ generation was so naive. They thought they had left caste behind when they came to the United States. They were steeped in a desperate optimism, being among the first generation to benefit from affirmative action programs that enabled Dalits to access higher education and pursue professions abroad as part of a new wave of South Asian immigrants to the US in the 1970s. After all they had endured to become educated, my parents genuinely believed caste was in the rearview mirror; in truth, they also needed to push down the demons that had terrorized them at home. When I asked my mom about our caste, however, she recognized that we had not left it behind. And that perhaps the

demons of caste could never be escaped. Moreover, leaving the material and economic

conditions of caste doesn’t mean you have healed from the trauma of caste. And importantly it’s not just trauma from the past: Everywhere South Asians go, they bring

caste and trauma from caste apartheid. Caste migrates and spreads, reestablishing itself in

our new geographies as we arrive as settler colonials. Caste is embodied by all diasporic

South Asians, regardless of our ethnic, national, linguistic, religious, sexual, or political

affiliations.

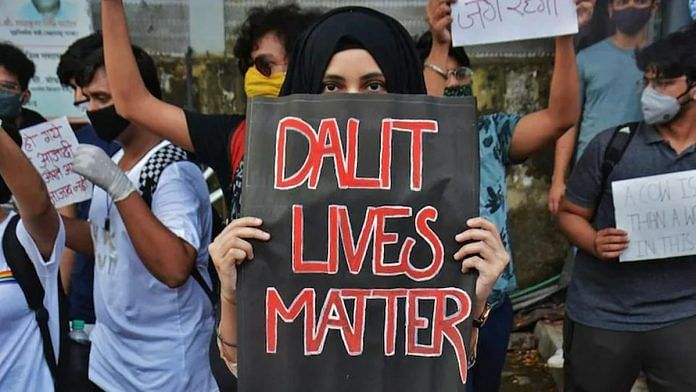

Although caste discrimination and caste-based violence in the United States are not as

widespread and overt as in South Asia, they exist here as well. In 2015 Equality Labs

conducted the first-ever survey about caste in the U.S. I worked with the indefatigable

Dr. Maari Zwick-Maitreyi, who helmed this landmark contribution to Dalit feminist

scholarship in North America. We decided to conduct this survey after repeatedly hearing

Dalit Americans talk about the caste discrimination they had experienced, whereas

dominant-caste South Asian Americans said caste wasn’t an issue. It’s hard now to recall

a time when people didn’t acknowledge caste in the United States, but 2016 was a very

different moment. Many academics did not support breaking the taboo of caste, and a

culture of silence and denial ran rampant within the South Asian American community.

Dalits were also afraid to be publicly identified and spoke openly about their fears about

being outed. Despite that fear, people trusted our team, and we were honored to reach out

to hundreds of South Asian groups across caste, language, and political spectrums.

While we gathered data, interviewing people in front of South Asian markets, businesses,

and religious centers, dominant-caste individuals hurled caste slurs at us. Our researchers

in multiple states all experienced open bigotry and disgust. One South Asian organization

had an existential crisis over the survey and convened a board meeting to debate sharing

the survey. We stood before that board with courage and explained that the community

was already divided, so this data would create space for powerful conversations that

would not only document the problem but also help everyone heal. That organization and

many others eventually pushed the survey throughout the US. Our hard work helped shed

light on caste bias and inspired a new generation of truth telling to dismantle caste

supremacy.

Indeed, it is fascinating to look at American history through the lens of caste. Some of the

very first records mentioning South Asian immigrants date from the 1700s. Reverend

William Bentley, a minister in Salem, Massachusetts, wrote in his diaries about the first

Indian who arrived in Salem: “I had the pleasure of seeing for the first time, a native of

Indies, who was from Madras. He was of dark complexion, had long black hair and soft

countenance. He was tall and well proportioned. He is said to be darker than Indians in

general of his own cast.” With (we can only assume) nearly no knowledge of India, the

good reverend mentions caste. Likely the Indian he met wanted to emphasize that he was

not lower-caste when he noted his complexion.

Also read: Ambedkar tried taking the caste issue to the United Nations. It had lessons for India

According to the records of the South Asian American Digital Archive, South Asians

began immigrating to the United States in larger numbers in the late 1800s. These early

immigrants were primarily Sikh men from the Punjab region of British India who settled

in the western parts of the United States (California, Oregon, and Washington) and

western Canada (British Columbia). They fled the English’s brutal colonial regime that

forced Indians to grow cash crops rather than food to benefit a booming industrial

Britain. Affected by drought, famine, and back-breaking taxation, they looked abroad for

better prospects. For the most part they worked in the US and Canada as laborers in

fields, lumberyards, and mills. They helped build the railroads and, alongside Mexican

and Filipino laborers, cleared the swamps in California’s Central Valley to create fertile

farmland.

In the personal archives of Dalit Canadian Anita Lal’s family, we have an early account

of harm done to Dalits by dominant-caste immigrants within the community of Punjabi

Sikh laborers on the west coast. Anita’s family is one of the oldest Dalit families in North

America, and the testimony of her great-grandfather Maiha Ram Mehmi on his experience of casteism in the lumber mills of British Columbia reveals just how long caste has been here in the Americas. When he first came to work in the lumber mill, the dominant castes would not allow him to eat with them; he had to eat alone in his room. He was also forbidden to take shifts in the cookhouse, due to the fact that he was considered impure and dirty. Interestingly enough, a dominant-caste Hindu foreman, Kapoor Singh, noticed this dynamic. When he discovered the cause of the exclusion, he insisted that all workers eat in the same place. This account is one of the first known examples of untouchability in North America; we can only imagine how many more went unrecorded. Here is a brutal reminder that caste-based discrimination in the workplace was happening as soon as South Asians arrived in North America—and it has never stopped.

Under caste apartheid, South Asian immigrants are socialized to preserve their caste-group status at the expense of others by fighting to maintain their own caste’s privilege and thus reinforce the larger hierarchy of caste, like the proverbial crabs in a barrel. In this way, the structures and psychology of caste have been fundamentally damaging to cross-community solidarity building. A key part of the casteist mindset is the assertion that “upper” castes have earned their positions through “merit,” “skill,” and “hard work,” as opposed to those “beneath” them in the caste system who are “freeloaders” “without merit” who only succeed thanks to government policies like affirmative action. This toxic narrative carries over to the US and impacts immigration debates. Skill and merit transform into classist and racist dog whistles among dominant-caste South Asian immigrants who wield it to distinguish themselves from Black, Brown, and Indigenous immigrants. The casteist mindset informs a racist mindset that creates categories of “good, educated” immigrants versus “bad” immigrants who are undocumented or in working-class jobs.

The anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity within high-caste South Asian communities that pursue white adjacency is not a true route to dignity for our communities and ultimately leads to more discrimination for everybody. This history proves that when we don’t reflect on our own internal systems of oppression, we in turn often create harm for Black Americans, other communities of color, and Indigenous peoples.

Also read: Sindhis are not a caste-free society. My interviews show it is just a false claim

In 1965, thanks to the efforts of the civil rights movement, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act passed and the criteria for immigration were diversified. The 1970s and 1980s saw a new wave of immigrants. Those from South Asia were mostly well-educated, dominant-caste professionals; they became doctors, lawyers, accountants, and entrepreneurs. Smaller numbers of Dalit and other caste-oppressed immigrants, including my parents, who benefited from affirmative action programs in India also arrived in the US at this time. They found themselves caught between heavily casteist immigrant networks and hostile white-supremacist institutions. As a result, most Dalits hid their identity or stayed away from South Asian communities altogether. This led to the unfortunate development of many South Asian immigrant civic, religious, and political institutions being created mostly by dominant-caste immigrants who established dominant-caste Hindu culture as the norm for all South Asian Americans, while the culture, religion, and practices of caste-oppressed immigrants were sidelined.

More recently, the Immigration Act of 1990 created the H-1B visa program, which began a new wave of South Asian American migration comprising many IT professionals. The caste demographics have since shifted, as even larger caste-oppressed populations have arrived in significant numbers due to affirmative action policies for Dalits in our countries of origin.

Over the past thirty years, many different kinds of caste-discrimination cases and stories have since emerged. These cases emphasize that in the United States questions of caste are clearly new frontiers for civil, human, and workers’ rights.

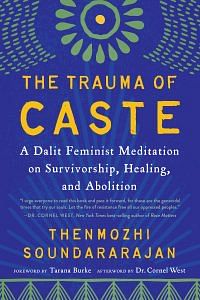

This excerpt from The Trauma of Caste by Thenmozhi Soundarajan has been published with permission from North Atlantic Books.

This excerpt from The Trauma of Caste by Thenmozhi Soundarajan has been published with permission from North Atlantic Books.