A phone rang around 9 p.m. in New York City’s Upper East Side neighborhood.

“Namaste, is guru-ji there?” enquired a quiet, measured voice. “Father, I believe India’s next Prime Minister is on the line for you,” came the instinctive reply. There had been rumors, after all.

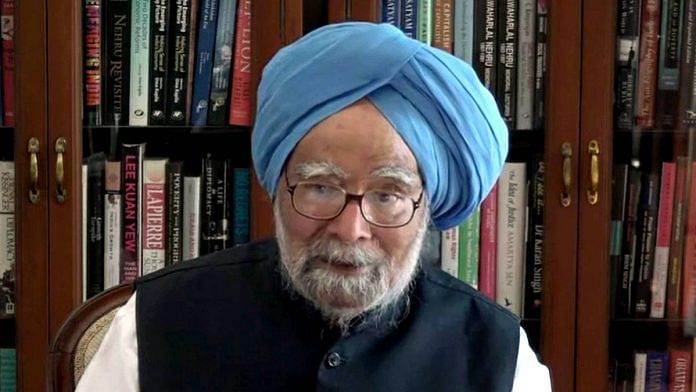

“I have been expecting your call, Manmohan.” The elderly voice of a teacher or guru, a fellow technocrat who had dependably served Mrs. Indira Gandhi 30 years earlier, came calmingly through the phone in Delhi.

“What is your counsel, guru-ji? This game is not for me. We are not supposed to be politicians. I’m an economist.”

There was a pause. And then a response. “The first thing you must do, Manmohan, is sit down and write your resignation letter. Place it in your pocket and take it into work every single day. You have no idea the compromises you will have to make and the battles you will have to fight.”

May 13, 2004, was a momentous day for the Indian National Congress. Against the predictions of pollsters, the party rose to power at the federal level, or center, in a coalition government. It was the return of India’s “Grand Old Party” after eight years of political exile on the opposition benches. Just a week later, a different coalition was born, this time unprecedented in the history of Indian politics. On May 22, 2004, India’s technocrat prime minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, walked into Parliament’s Ashoka Hall for his swearing-in ceremony. After taking his oath, he approached Mrs. Sonia Gandhi and gave a slight bow of respect. Although Mrs. Gandhi’s ability to build a left-leaning coalition, premised on constructing a government for the “common man” (aam aadmi), had won Congress the highest office in India, it would be the former finance minister and chief architect of the 1991 neoliberal reforms, Dr. Singh, who had been anointed by the Gandhi family to sit in that most coveted seat.

Bringing ideas back in

How do ideas shape government decision-making? Comparativist scholarship conventionally gives unbridled primacy to external, material interests—such as votes and rents—as proximately shaping political behavior. These logics tend to explicate elite decision-making around elections and pork barrel politics but fall short in explaining political conduct during credibility crises, such as democratic governments facing anti-corruption movements. In these instances of high political uncertainty, I argue in this book, elite ideas, for example concepts of the nation or technical diagnoses of socioeconomic development, dominate policymaking. Scholars leverage these arguments in the fields of international relations, American politics, and the political economy of development. But an account of ideas activating or constraining executive action in developing democracies, where material pressures are high, is found wanting.

The purpose of this book is to trace where ideas come from, how they are chosen, and, above all, when they can be the most salient for political behavior in developing democracies. The study focuses on India, with similar settings, including Brazil, Turkey, and Indonesia, among others, explored in the concluding section.

In most developing democracies, state institutions are not neutral arenas, but rather reflect government decision-makers’ preferences and power. Rather than consider Indian politics as a contest among competing figures with clear and stable interests who develop strategies to pursue those objective interests, this book develops a vision of Indian politics as a struggle for power and control among decision-making elites who are motivated by a myriad of ideas.

Fundamentally, this requires us to understand decision-making elites, and the subset of political leaders specifically, and how they develop and deploy their preferences to structure institutions. Therefore, we will consider the questions explored in this book through a constructivist approach in which advances in historical institutionalist studies allow theorization of the interactions between ideas, human agents, and political and state structures. After all, when actors interpret their interests and preferences using an ideational framework, they are also deeply conscious of power. Elites in this book are denoted as decision-makers within the executive arena, chiefly the prime minister, and include the cabinet and other offices, party officials, and institutions that interact regularly

with the executive and maintain key political economy powers. The specific set of ideas identified and reduced in this book revolve around concepts of the nation as well as technical ideas around social and economic development.

Also read: To understand Vajpayee’s economic worldview, look at his first choice for finance minister

Research puzzle

The puzzle animating this book began to take shape in the summer of 2012. That July, I witnessed thousands of citizens from across India take to the streets in her capital, New Delhi. The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition government of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh faced its biggest civic challenge in an anti-corruption movement led by supporters of the activist Anna Hazare, a veteran social justice campaigner who had undertaken a hunger strike in New Delhi. The India Against Corruption (IAC) movement reached a crescendo due to deteriorating economic conditions and a sequence of high-profile corruption scandals that implicated senior officials all the way up to the prime minister. The government found itself in the midst of a credibility crisis. Fast forward to the smoldering summer months of 2013, when the cries of citizens across developing world democracies—from Chile, Brazil, and Mexico to Turkey and Indonesia—raised the global volume of movements calling for better central governance through the eradication of corruption, which would reverberate throughout that decade. Each government faced mounting pressure, and several closed in on re-election campaigns. Some, such as in Turkey, arbitrarily crushed the anti-corruption groundswell, while others, such as Brazil, were compelled into negotiated concessions. These fascinating trends piqued my interest in these movements, the credibility crisis environment in which they swelled, and, more intriguingly, the determinants of government responses to anti-corruption movements—the motivating empirical question explored in this book.

A nationwide anti-corruption movement creates a credibility crisis environment where political uncertainty obfuscates state elites’ understanding of predictable interests, such as votes and rents. The full range of alternative strategies and their relative costs become narrowed. Such situations are hardly uncommon in matters of political interest, and are especially frequent in the messy political realities of India and plausibly other developing country contexts. Given the volatility of uncertain political situations, decision-makers are unsure about what their objective interests are, let alone how to maximize the utility of these interests. This book argues that in such distinctive moments, or critical junctures that disrupt the existing social, political, and economic balance, the waters of statistical prediction are muddied. Instead, decision-makers seek to reconstitute interests, and establish narratives regarding the causation behind the crisis and functions of the respective anti-corruption movements. In this scenario, ideas serve as “weapons” between decision-making elites in the struggle to diagnose the overall crisis, and re-establish credibility to reduce uncertainty.

This excerpt from ‘When Ideas Matter’ by Bilal A. Baloch has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.

This excerpt from ‘When Ideas Matter’ by Bilal A. Baloch has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.