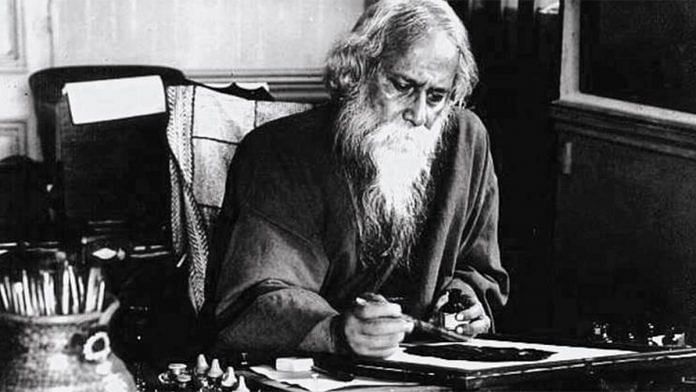

Rabindranath Tagore is highly revered as a renowned poet, essayist, musician, and artist from Calcutta. He is the founder of the university town Shankiniketan, and the author of India’s national anthem.

If the public sphere was underdeveloped and there were few public spokesmen, if the life of the mind was constrained by the colonial environment, the intellectuals had to play a multidimensional role. Tagore played a variety of roles. He was a poet, a preacher, a teacher, and a patriot, and, indeed, to some of his admirers almost a prophet. In an amusing letter to Andrews in 1921 he writes of the inner conflicts as a result of this multiplicity of roles:

Sometimes it amuses me to see the struggle for supremacy that is going on between different persons within me… When the call comes to me to take some part, in some manner or other, in some political affair, the Poet at once feels nervous, thinking that his claims are likely to be ignored, simply because he is the most useless member in the confederacy of my personality… I sit dumb and muse and sigh, when sheaves of newspaper cuttings are poured upon my table, and a leer is spread upon the face of the Practical man; he winks at the Patriotic man sitting solemnly by his side; and the man who is Good, thinks it is his painful duty to oppose the Poet, whom he is ready to treat with some indulgence within proper limits… I jump up from my judgement-seat and holding the Poet by hand, dance a jig and sing, ‘I shall join you, comrade, and be drunk and gloriously useless.’

In the letter that followed Tagore added that ‘I have a great deal of the patriot and politician in me, and therefore I am frightened of them; and I have an inner struggle against submitting myself to their sway’. And again:

when the touch of spring is in the air, I suddenly wake up from my nightmare of giving ‘messages’ and remember that I belong to the eternal band of good-for-nothings; I hasten to join their vagabond chorus… Is it not good for the world that a poet should forget all about resolutions carried in monster meetings.

And again: ‘Why should I be anything else but a poet? Was I not born a music-maker?’

The responsibility of being on a ‘mission’ was particularly irksome to Tagore when he took to lecturing, collecting funds for his school, meeting the media, etc. ‘I wish that I could be released from this mission. For such missions are like a mist that envelops our soul…’ He wrote this from America in 1921, one of his most successful trips. And laughing at himself he added: ‘I rouse myself, strain my mind, raise my voice for prophetic utterances… and to my utter dismay, discover I am not a leader, not a teacher, and farthest of all from being a prophet.’ Tagore perceived ‘conflicts within my nature.’ Among other causes the conflict between ‘absolute poetdom’ and doing-good-to-others was a major cause of internal conflict. The basic problem was that, ‘Poesy creates its own solitude’, whereas doing-good takes one into the crowd and dependence on organisation and ‘means and materials that are outside me’. Hence a role conflict.

The second problem was the quest for popularity. That is because ‘when a person has some mission of doing some kind of public good, his popularity becomes the best asset for him.’ Hence there develops a craving for popularity and for public honours. ‘The man who constantly receives honour from admiring crowds has the grave danger of developing a habit of mental parasitism upon such honour… I become frightened of such a possibility in me, for it is vulgar.’ On the other hand, the poet ‘is appointed to the perpetual comradeship of man—not as a guide, but as companion’, therefore the poet has no need for a following, a crowd of people. Therefore, Tagore felt that since his only true place in the world was that of the poet, ‘One day I shall have to fight my way out of my own reputation.’

There was a third source of internal conflict as Tagore perceived it. ‘Ever since the scheme of the international university [i.e., VisvaBharati at Santiniketan] has been made public, the conflict in my mind has been unceasing—the conflict between the vision of the ideal and the vision of success.’ There was, he felt, always the danger that the Truth or the values at the core of the ideal might be compromised for the sake of success in that endeavour. He was aware that ‘all over the world the prudent and the wise are in the habit of making a pact with Mephistopheles’, and thus to put in danger the real god. In a letter to Charles Andrews, Tagore writes in the middle of 1921: what ‘creates conflict within my nature’ is the fact that ‘I have to deal with and make use of men who have more faith in the material part [of setting up an institution] than in the creative ideal. My work is not for the success of the work itself, but for the realization of the ideal.’ The men whom he needed for building and running an institution were ‘ready for all kinds of compromise’ and ‘when you say that the result is not greater than the idea itself, then they laugh at you.’

Of all the three sources of ‘inner conflict’ Tagore mentions, the most recurrent one, mentioned most often is the conflict between his poetic self and other selves. Sometimes he felt that a via media was possible; for example, when he wrote to W.W. Pearson in 1918: ‘It is not by meticulous care in avoiding all contaminations that we can keep our spirit clean and give it grace, but by urging it to give vigorous expression to its inner life in the midst of all the dust and heat’ of life in the outer world. But probably Tagore found this difficult in course of time as the demands on him from the outer world multiplied. His private letters reveal that most of the time Tagore was torn between his loyalty to his Muse and his sense of responsibility to society.

My heart… is like a leaky boat, full of water, that can just keep itself afloat, but the least burden of responsibility becomes too much for it… I want to say ‘No’ emphatically to all the importunities of the world, to all the social and moral obligations.

The result of this conflict was that he felt ‘oppressed with a burden whose nature we hardly know.’

Beyond the conflicts between the different roles Tagore perceived at different times, there was one constancy: Tagore thought of himself essentially as a poet. He writes to Charles Andrews from Chicago in 1921: ‘Why should I be anything else but a poet?’ And again:

When I came to this world I had nothing but a reed given to me, which was to find its only value in producing music… But now came the schoolmaster in the midst of my dream-world… I left aside my reed… In a moment I became old and carried the burden of wisdom on my back, hawking truths from door to door. Why have I been made to carry this burden, I ask myself over and again, shouting myself hoarse in this noisy world where everybody is crying up his own wares? Pushing the wheelbarrow of propaganda from continent to continent—is this going to be the climax of the poet’s life? It seems to me like an evil dream, from which I occasionally wake up at the dead of night and grope about in the bed asking myself in consternation: ‘Where is my music?’ It is lost… You know that I have said somewhere that ‘God praises me when I do good, but God loves me when I sing.’… How I wish I could find my reed again… When I know for certain that I shall never be able to go back to that sweet obscurity which is the birthplace of flowers and songs, I feel homesick.

This excerpt was taken with permission from the book ‘Rabindranath Tagore: An Interpretation’ by Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, former professor of history at Jawaharlal Nehru University and ex-Chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research. It was published by Penguin Random House India in 2017.

This excerpt was taken with permission from the book ‘Rabindranath Tagore: An Interpretation’ by Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, former professor of history at Jawaharlal Nehru University and ex-Chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research. It was published by Penguin Random House India in 2017.

Also read: Tamil poet Subramania Bharati’s lesser-known love affair with Rabindranath Tagore’s work