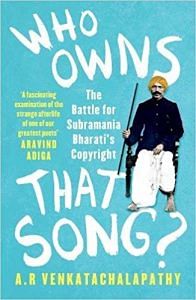

A.R. Venkatachalapathy’s book Who Owns That Song? The Battle for Subramania Bharati’s Copyright traces the journey of Bharati, the first poet whose works were nationalised.

Bharati’s interest in Tagore and his consequent attempt at translating him is a remarkable story, where a great poet unbeknown to another great poet followed his work and paid generous tribute.

Bharati was born twenty-one years after Rabindranath Tagore and predeceased Tagore by exactly twenty years. During his short life, Bharati demonstrated a remarkable engagement with Tagore and his writings – not only did he comment on Tagore’s works frequently but also translated a considerable number of his essays and short stories.

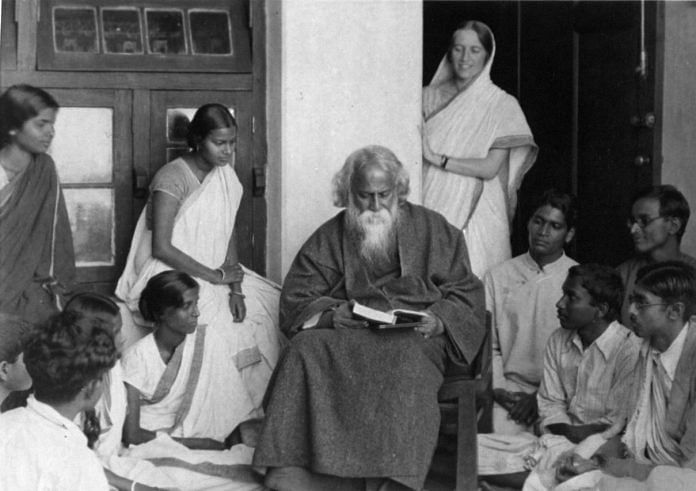

The two poets never met. Bharati visited Calcutta in December 1906 for the annual session of the Congress but did not run into Tagore. Did he even know of Tagore and his writings at this point in time? Unlikely. More than a decade later, in early 1919, Tagore travelled to the south – to Madurai, Tiruchy, Thanjavur, Kumbakonam and Chennai. Bharati had been released from prison only a few months earlier; a broken man, he was still trying to find his feet in British India. By this time, Bharati had become more than familiar with Tagore’s works. He was probably in Chennai when Tagore gave a talk at Gokhale Hall on 10 March, for Bharati himself had lectured not too far from there at the Victoria Public Hall about a week earlier. Tagore had come on a fundraising tour for Visva- Bharati at the instance of the Irish poet J.H. Cousins, who could claim some familiarity with Bharati’s writings and had even translated a couple of Bharati’s poems into English. The press gave Tagore’s visit extensive coverage and it is impossible that Bharati could have missed it, but there is no record of him having had even a glimpse of Tagore. Given that Bharati was at this point being pre-censored by the police and was being shadowed, he might be condoned for having given Tagore a miss. If the two had met, it would have been worthy of record. Did Tagore, later in his life, come to know of Bharati’s existence? That too remains unknown.

Between these two moments – Bharati’s Calcutta visit in 1906 and Tagore’s Chennai visit in 1919 – much water had flown under the bridge. This period, coinciding with Bharati’s writing career, was marked by his engagement with the writings and reputation of Tagore.

A product of the Swadeshi Movement, Bharati was its perceptive chronicler and commentator, though unlike Tagore, he was not its critic. Bharati was up to his ears with the happenings in Bengal, commenting on and excerpting from Bengal journals. He translated Bankim’s ‘Bande Mataram’ into Tamil (twice, actually). But, surprisingly and interestingly, there’s no reference to Tagore at all during this time, between 1905 and 1911. One wonders what Bharati might have thought of Tagore’s ambivalence towards the Swadeshi Movement after the Jamalpur riots (1907), considering that Bharati never saw the underbelly of nationalism. (We also don’t know if Bharati had read and had an opinion on The Home and the World, a novel that illustrates Tagore’s ambivalence about the movement.)

Bharati’s first reference to Tagore is after the latter won the Nobel Prize in 1913. He invoked Tagore to express his opinion on Annie Besant’s involvement in the freedom struggle. In response to an essay criticizing the nationalists for accepting Annie Besant’s interventions in politics, Bharati wrote in The Hindu that this was fine so long as she did not involve herself in religious affairs and did not expect to become a leader of Indians in any regard. ‘Intellectually and morally we have men in our land, and women, too, who cannot in the nature of things be dominated by her personality.’ And what was the evidence on which Bharati asserted this? ‘We produce men like Tagore and Bose nowadays.’

A correspondent of The Hindu who met Bharati in Pondicherry observed that given ‘his manner of speaking emphasised as it is by tremendous thumping, sudden getting-up and sudden collapses’ he ‘remember[ed] nothing out of all his tirade, except his classification of Tilak as the first Indian statesman of the ages, of Prof. J.C. [ Jagadish Chandra] Bose as the first scientist, and Rabindranath Tagore as the first Indian poet’.

Bharati’s first real reference to Tagore comes in an essay written in November 1915. Narrating the now-familiar tale of ancient glory and medieval decline, Bharati saw the first rays of an Indian awakening during his time. ‘We now see the signs of resurgence in everything. The Indian nation has been born anew. The whole world now acknowledges that Ravindranath is one of the mahakavis of our times.’ The global acknowledgement of Tagore was a recurrent theme in Bharati’s comments on Tagore.

Bharati translated into Tamil extracts from The Crescent Moon, a collection of poems and stories, and his joy in translating them is more than apparent. While these were prose translations, a year later he translated a Tagore poem on the glory of national education in four stanzas, from the same collection.

Bharati commented at length on Tagore’s 1916 talk at the Imperial University of Tokyo and translated extensive passages from it. He saw Tagore’s message as the awakening of a sleeping Asia by Japan. In his view, Tagore was only continuing Vivekananda’s task. ‘Vivekananda only revealed the exercise of the spirit. Tagore has now been sent by Mother India to show to the world that worldly life, true poetry and spiritual knowledge are rooted in the same dharma.’ Assessing Tagore’s credentials for this task, Bharati continues: ‘Gitanjali and the other books that he has translated and published in English are short. They are not extended epics or big plays. He revealed just a few lines of his lyrics. But the world was amazed.’

Excerpted with permission from Juggernaut Books

Excerpted with permission from Juggernaut Books