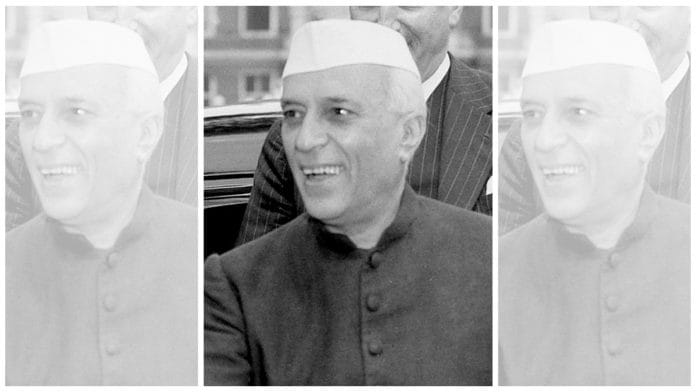

The horrors of partition were a wake-up call for Nehru. Some of his self-righteous certitudes were shaken by the violence of partition. He was appalled by the riots in Delhi, which he witnessed with his own eyes. Mass killings in September 1947 drove more than 300,000 Muslims out of the Old City of Shahjahanabad onto trains to Pakistan, or into makeshift refugee camps and shelters in the city itself. To Nehru’s distress, the Delhi administration seemed powerless, or unwilling, to stamp out the violence.

By 1951, Delhi’s demography was transformed. The city’s Muslim numbers had declined from almost a third (in 1941) to just under six per cent. Thousands of Muslim refugees fled to the mausoleum of Humayun, the second Mughal emperor, which lies a few miles south of the Old City. Perhaps its high sandstone walls gave them a sense of protection. Perhaps a sense of Mughal authority still attached itself to these proud relics of a bygone era, and perhaps they took comfort in this. Rehabilitation for displaced Muslims was appalling. Attia Hosain’s novel Sunlight on a Broken Column evokes their horrors.

That their plight moved Nehru is plain: he wandered round Delhi like a man in shock (rather like the Mahatma had done in Noakhali in East Bengal), seeking to quell the lynchings himself. He admonished Vallabhbhai Patel, with whom his relationship was now worsening by the day. He confronted his home minister about the slackness and communal bias of the Delhi administration:

I realise that the situation was too big for almost any person to handle satisfactorily and it came with some suddenness . . . [But] as far as I can make out, we have had to face a very definite and well-organised attempt of certain Hindu and Sikh fascist elements to overturn the Government, or at least to break up its present character. It has been something much more than a communal disturbance. Many of these people have been brutal and callous in the extreme. They have functioned as pure terrorists . . . Last night’s incidents when four Muslims in Safdarjung Hospital were killed in their wards is a horrible reminder of the type of persons we have to deal with.

Patel demurred, and this was one of many points on which the two men fell apart.

After the Delhi riots, Nehru began to recognise that minorities indeed required protections over and above the rights that all citizens of the free nation should enjoy – Jinnah had been right after all. Gingerly, and not always with courage, he began to take up the mantle of what would come to be deemed the ‘secular’ and ‘Nehruvian’ approach to nationhood, and began to speak about an India in which everyone had a place, in which the culture and faith of minorities would be guaranteed protection, and where ‘unity in diversity’ would be celebrated. This was a very particular sort of secularism, which mixed elements of the ‘composite nationalism’ of old with new discourses of citizenship, economic uplift and development.

In developing this vision, Nehru drew on the thinking of Muslim intellectuals and ‘nationalists’ who had stayed on in India – Muhammad Mujeeb and Zakir Hussain in particular, but also Maulana Azad, who served as India’s first minister of education. French-style laïcité this was not: it did not seek to deny religion or drive it totally out of the public domain. (That would have been fruitless anywhere in South Asia.) It was a vernacular secularism evolved in the particular context of India after partition, designed to enable religious minorities and their rich cultures to survive, perhaps even to thrive.

In 1947, however, it was not at all clear that this vision of India would triumph, because others drew a different lesson from the carnage. Those on the Hindu right veered further to the extreme, finding proof in partition’s violence that all Muslims were murderous – a danger to all Hindus. In their uncompromising view, the thirty-five million Muslims who remained in India should be disarmed and cowed. India should be declared a Hindu nation forthwith. Muslims should be denied all citizenship rights, and forced to leave for the Pakistan ‘they’ had demanded. Those who stayed on in India should know that they did so on sufferance, provided that ‘they behaved’. On 28 July 1947, eighteen days before independence and partition, an all-India conference of Hindu Congressmen resolved that they

must exert their influence to see that this partition becomes real and those who clamoured for a ‘homeland’ of Pakistan for themselves leave this country and make themselves comfortable in their homeland, so that this partition plan may become a real and lasting solution of the Hindu–Muslim problem once and for all. All Muslim members of the constituent assembly should be debarred from the membership of the assembly, as they have ceased to be the nationals of Hindustan.

Muslims had to assimilate into the Hindu way: they must stop eating beef and stop publicly performing go-korbaani (cow sacrifice) during Eid. That many Muslims accepted these terms without protest did not appease the extremists. The Hindu Mahasabha (the Hindu nationalist political party), whose leader Dr Syama Prasad Mookerji by this time had joined the cabinet, pushed for a war with Pakistan to grab more territory from it on which to house Hindu refugees. In October 1947, a brief and contained war had already begun in Kashmir, but the Hindu hawks wanted to go further still. They also bitterly opposed giving Pakistan its due in the division of assets and liabilities inherited from the British Raj.

Gandhi, in contrast, was vocal about the need to be fair to Pakistan in these negotiations. Long a bogeyman in the eyes of the extreme right, they now attacked the old man for ‘selling out’ to Pakistan.

In late January 1948, the Mahatma was staying at the mansion belonging to wealthy industrialists, the Birlas, in Lutyens’ New Delhi. My husband Anil (then a child) happened to be staying with a family friend next door. On 29 January Gandhi, who delighted in children – often interrupting serious political business to join in their games – joined the ‘tennis ball’ cricket match that was underway. Anil was at the crease. Using a slow, wily, underarm technique, the Mahatma bowled him out with his first ball.

The next evening Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, shot Gandhi three times in the chest at point-blank range. The Mahatma, then seventy-eight years old, was at one of his daily prayer meetings. In the last months of his life he had been a Lear-like figure, refusing to participate in the independence celebrations, rushing hither and yon trying to quell the communal fires, whether in the Punjab, Calcutta or Noakhali in Bengal.

This excerpt from Joya Chatterji’s ‘Shadows at Noon- The South Asian Twentieth Century’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Joya Chatterji’s ‘Shadows at Noon- The South Asian Twentieth Century’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.