After the 2014 general election and the installation of the NDA government, the question of successfully piloting government-sponsored legislation through the Rajya Sabha and obtaining for it the concurrence of the opposition parties became a matter of high priority. In that context, a suggestion emanated from the Leader of the House that an Indian equivalent of what is known as the Salisbury Doctrine in British parliamentary practice should be instituted. This emerged from the working arrangements reached during the Labour Government of 1945–51, when the fifth Marquess of Salisbury was the Leader of the Conservative Opposition in the Lords. The Convention ensures that major government bills can get through the Lords when the government of the day has no majority in the Lords. In practice, it meant that the House of Lords does not try to vote down a government bill mentioned in an election manifesto.

This was strongly opposed by different sections of the House. It was pointed out that unlike the House of Lords, the Rajya Sabha is an elected House, integral to the federal and basic structure of the Constitution. In the discussion on the suggestion, some members even felt that the suggestion constituted a Breach of Privilege. I examined the matter carefully and accepted Arun Jaitley’s contention that his observation was ‘purely academic in nature’ and was not intended to show disrespect to the members. I concluded that since the Rajya Sabha is an elected House, the Salisbury Doctrine or any variant of it has no relevance to it.

During 2014–15, a demand was raised by the government floor managers that a bill may be allowed to be passed in the din in the Rajya Sabha. It was pointed out to them that while there were instances in the past when bills were indeed passed in the din, that happened with a necessary precondition that the government had a majority in the House. With a paper majority, the bills at times were cleared with voice vote, provided no one asked for the division of votes. However, in the current case, the ruling NDA did not have the majority. So, it was technically, procedurally and morally impossible to pass the bills in din, assuming the majority for the government.

Also read: Ansari gets bouquets from Modi, brickbats from PM’s supporters on last day as VP

Furthermore and during the UPA period, I had taken a position that no bills will be passed in the din. This was appreciated by the principal Opposition leaders. This principle of ‘no bill to be passed in din’ was steadfastly observed throughout my tenure. It did bring discomfiture to both the governments, but the UPA took cognizance of my principled stand and compensated it by floor management and adjustments with the Opposition. The NDA, on the other hand, felt that its majority in the Lok Sabha gave it the ‘moral’ right to prevail over procedural impediments in the Rajya Sabha. An expression of this was conveyed to me authoritatively, and somewhat unusually, when one day PM Modi walked into my Rajya Sabha office unscheduled. After I got over my surprise, I made the customary gestures of hospitality. He said that ‘there are expectations of higher responsibilities for you but you are not helping me’. I said that my work in the Rajya Sabha, and outside, is public knowledge. ‘Why are bills not being passed in the din?’ he asked. I replied that the Leader of the House and his colleagues, when in Opposition, had appreciated the ruling that no bills will be passed in the din and that normal procedures of obtaining consent will be observed.

He then said that the Rajya Sabha TV was not favourable to the government. My response was that while I had a role in the establishment of the channel, I had no control over the editorial content and that a committee of Rajya Sabha members, in which the BJP was represented, provided broad guidance to the channel, adding that from all accounts, the channel’s programmes and discussions were appreciated by the viewers.

Also read: Do Muslims matter for Modi-Shah BJP, or India?

A variant of this view, more troublesome for the Rajya Sabha, was the emergence of a practice of using the provisions of Articles 109 and 110 of the Constitution relating to money bills and to designate legislation having incidental financial implications as money bills on the strength of the certification of the Speaker of the House of the People in terms of Article 110(3). Such proposals, in the view of many members, would be within the ambit of Article 110(2) but made no headway in view of the absolute authority bestowed on the Speaker’s certification. It came to the fore in the context of the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016 and was even challenged, unsuccessfully, by a member in the Supreme Court of India. However, the majority bench agreed that the Speaker’s discretion in declaring a bill as a money bill can, henceforth, be subject to judicial review. On 13 November 2019, the Court, however, decided to refer the matter to a larger constitutional bench.

The use of this procedural detour became evident when in 2017 (up to 10 August) out of the 31 bills passed/returned/deemed to be returned by the Rajya Sabha, 16 were money bills.

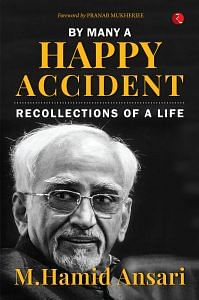

This excerpt from ‘By Many A Happy Accident: Recollections Of A Life’ by M. Hamid Ansari has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from ‘By Many A Happy Accident: Recollections Of A Life’ by M. Hamid Ansari has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

Fake gandhis who controlled this blatant traitor and jihadi are the most corrupt despicable and hated traitorous criminals in India.

A Muslim who never could become an Indian despite being showered with choicest of office which he didn’t deserve.

Only acted as a servant of the Italian Gandhi and was happy doing her bidding and scuttling Rajya sabha or any other voice for her.

An High IQ person who occupied high position with low trust credit on National interests as noted by RAW officials suring his middle east stay as an ambassodor and the way he commneted after demiting the highest office

Hamid Ansari should thank Congress that he isn’t tried for Treason.

thePrint should do a analysis of Hamid Ansari stint as diplomat in middle East.

he will only talk about what modi did or said. he will not have the spine to talk about either the gandhi family or the congress govt.

Only cut throat businessmen expect to win & have upper hand in every transaction

Rajya Sabha was not envisaged as a forum of election loosers who don’t have public support, to veto and oppose everything the government does. It is supposed to handle situation where the government is doing completely wrong things. If it will always stop bills using anarchy, then why have elections at all, just let the election loosers detect how the country will be run ?