When bacteria, virus, or other pathogens attack our bodies, we produce vast quantities of antibodies.

Secreted by blood, these proteins stick to the invaders and aid their destruction. This is our primary defence mechanism. Insects, however, lack antibodies, but they don’t keel over and die at the first symptom of a disease.

Social insects such as honeybees live in densely packed hives and ought to be prone to infection. Queen bees rarely, if ever, leave the colony. Hard-working worker bees range far and wide to gather pollen and nectar. While they go about their business, they pick up germs. Back at the hive, they use the contaminated pollen to create royal jelly to feed the queen. These pathogens could blaze through the nest and destroy it. How do insects survive disease?

Scientists thought if insects didn’t have antibodies, they must have a primitive immune system. Crystal cells in the hemolymph (or insect blood) immobilize the invading microbes, and plasmocytes (like our white blood cells) swallow them. But that’s not the only defence.

After the researchers injected bacteria into fruit flies, the hemolymph ignited with antibacterial activity. A fat body (similar to our liver) within the circulatory system produced quantities of infection-fighting peptides. Even dead bacteria triggered this reaction.

Some insects, like mealworm beetles, red flour beetles, and cabbage leaf hoppers, don’t stop with putting up a fight against pathogens. They confer the resistance they develop to their brood, similar to children inheriting antibodies from the mother. What is the mechanism of this antibody-free immunity?

Scientists led by Dalial Freitak, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki, found the key is vitellogenin, a hormone-like protein found in egg yolk and the hemolymph of insects.

Within the egg, it is a nutrient for developing embryos. But it is vital in healing inflammation and injury. It also dictates lifespan – the hemolymph of short-lived worker bees has concentrations of up to 40 per cent of vitellogenin while longer-lived queens have up to 70 per cent.

Freitak met Heli Salmela, who was working on vitellogenin for her doctoral thesis, at a group meeting at Helsinki University, Finland. ‘She presented her data on the capacity of vitellogenin to bind with bacterial pieces,’ says Freitak.

Since it is also an egg protein, could vitellogenin transmit immunity to the next generation? Together with Gro Amdam, at the Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences, they designed an experiment to test that theory.

They applied vitellogenin to some dissected ovaries of queen bees but not others, and then introduced fluorescent fragments of Escherichia coli to all of them. The ones that didn’t get the protein didn’t absorb the microbial pieces. When the researchers saw the vitellogenin-treated ovaries sucking up the fragments, they grew excited.

‘I felt like I had won the lottery!’ says Freitak. ‘I don’t think I have ever been as happy as when I saw the images of ovaries, full with fluorescent bacterial pieces in the vitellogenin treatment. We danced in the lab with Heli.’

The researchers also proved vitellogenin, and not any of the other proteins in the hemolymph, played the leading role in triggering an immune response.

‘What we found is that it’s as simple as eating,’ Gro Amdam said in a statement. When honeybee workers bring pathogens back to the hive and feed the contaminated jelly to the queen, she digests and stores them in the fat body. Her hemolymph carries the protein-wrapped microbial strands to the developing eggs in the ovaries, priming the immunity of the next generation. Bees are born vaccinated and ready to fight diseases in their environment. These insects had evolved a vaccination system millions of years ago. The mystery of how insects inherit immunity that had vexed scientists for a long time had been solved.

Vitellogenin bonded more strongly with gram-positive bacteria like American and European foulbrood diseases than with gram-negative bacteria like E.coli. Spores of the bacteria that causes American foul brood disease spread quickly through hives, wiping out entire colonies. The researchers suggest the intense reaction to these gram-positive microbes may reflect the severity of threat they pose to honey bee larvae.

This inherited immunity probably doesn’t last long in the bloodline and may be replaced by specific antidotes to other diseases as they occur in the bees’ environment.

Bees and other pollinating insects are crucial for agriculture, fertilizing the flowers of fruit and nut trees and vegetable crops. The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that 90 per cent of food in 146 countries is supplied by more than 100 crop species, most of which are pollinated by insects.

Now that the researchers have figured out how this defence mechanism works, they can develop an edible vaccine to deadly diseases like the foulbrood and feed it to honeybees. Conversely, they can also interfere with this acquired defence to control pest insects and their damage to crops.

Freitak says her team is testing and patenting a harmless vaccine against American foulbrood disease that can be introduced into bee hives in an edible cocktail. ‘They would then be able to stave off disease,’ she says. This would not only shore up honeybee immunity but also reduce the threat to human food security.

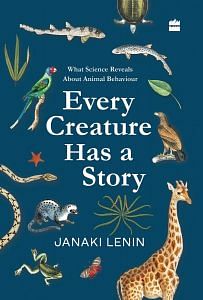

This excerpt from Every Creature Has A Story by Janaki Lenin has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.