In his book, Duvvuri Subbarao discusses how he dealt with a sceptical press and unwelcoming colleagues when he was first appointed governor of the RBI.

There was broad endorsement in the media of the Reserve Bank’s policy response to the crisis although there were some outliers — some saying that the Reserve Bank was doing too much by way of crisis management and others saying that we were doing too little.

In all of this, there were two strands of criticism from the commentariat during those early months which had disturbed me. The first was that I was compromising the Reserve Bank’s already fragile autonomy by allowing the government to dictate policy, confirming what some people suspected at the time of my appointment. The second criticism was that the Reserve Bank remained largely uncommunicative even as it was hyperactive on the policy front. The general refrain was that the Reserve Bank’s silence was jarring, especially when set against the flurry of comments from almost everyone in Delhi — whether on the inside track or not — about what should be done and what would be done by way of policy response to the crisis.

There was not much I could do about the criticism on diluting the Reserve Bank’s autonomy, not in the short-term anyway. The crisis was a black swan event, and everywhere around the world, governments, central banks and regulators were acting in concert and synchronizing their policy responses. What we were doing in India was no different from the global practice during those anxious and turbulent times. But my credentials were suspect because of my background as finance secretary and so lent credence to this criticism.

I was more sensitive to the criticism on the ‘eloquent silence’ of the Reserve Bank. This was by no means deliberate. In normal course, it would take at least a couple of months for the media to take a measure of a new governor, for both sides to get to know each other and for a protocol of communication to get established. The crisis did not allow us the time to go through this familiarization process at the normal pace. In part because of the lack of familiarity, I tended to neglect the communication dimension of my job in those early months.

The criticism was a welcome call for corrective action. My first response was to establish a practice of a media conference following every major crisis-response package by the Reserve Bank.

The first of this series of media conferences was on 28 October 2008, following the first quarterly policy review on my watch. I was not a novice in dealing with the press; I had in the past taken questions from reporters as finance secretary, and also given brief interviews. But facing a media conference as governor was an altogether different proposition since so much seemed to hang on what you said and how you said it. I had gone through answers to possible questions with the staff but I was still nervous. After all, this wasn’t any old time; we were going through a period of acute anxiety and uncertainty, and the media was struggling to interpret my actions and understand my personality. I knew they would be more probing than usual, but would they also be adversarial?

As I entered the conference room with the four deputy governors in tow at 3 p.m., a strange calm suddenly descended upon me. The conference didn’t exactly go as per script; in fact, no media conference does. But I never felt cornered or lost. I believe I gave cogent and reasoned replies to all the questions, including why I had to resort to an unscheduled policy action, that too one as significant as a regime change in monetary policy, just four days ahead of a scheduled policy review. One question that came up several times and in several formulations was whether the government was driving the Reserve Bank’s agenda. Beyond a simple denial, I chose not to join issue since any elaboration would have seemed defensive and unconvincing. Time alone should establish my credibility.

The press conference lasted an hour, longer than the typical thirty–forty-five minutes of post-policy conferences under my predecessor, Governor Reddy. It seemed a success on several fronts. The explanation of the rationale for the slew of crisis response measures gave the media an appreciation of the context in which we were operating; the media got a full, good look at me, enough to size up the new governor; and at a personal level for me, it drove away the fear of the unknown. Most importantly, it set the tone for a very constructive and happy relationship that I enjoyed with the media through my five-year term.

The criticism that I was ceding control of the Reserve Bank’s crisis response to the government was weighing on my mind, but as I said, there was nothing much I could do to reverse what I thought was an ill-informed view. Time alone would have to neutralize that.

My bigger concern though was whether I was, even at this very beginning of my tenure, losing credibility with my own staff in the Reserve Bank. What if they too became prejudiced by all the talk of my inability or unwillingness to protect the Reserve Bank’s turf? Instead of looking up to me for my professional competence and intellectual integrity, they would be looking at me with suspicion, and worse, distrust. This would hurt my reputation in many ways, but even more importantly, it would compromise my effectiveness, something that the Reserve Bank could not afford, least of all in a crisis situation like this.

Hopping from job to job and organization to organization is standard fare in an IAS officer’s career trajectory. With thirty-five years of civil-servant experience under my belt, I was quite aware that the default relationship between a new boss and the organization that he comes into laterally is of distrust and suspicion. The new boss has to work hard early on in his tenure to tear down those barriers and establish his credentials to earn the respect of his staff. But here I was, forced to perform at peak level, under high-profile visibility even before the large majority of the senior staff of the Reserve Bank, let alone the thousands of subordinate staff, got to know me. Besides, here I was interacting with the government much more actively than the Reserve Bank staff had been used to seeing. Would they give me the benefit of the doubt and evaluate my actions in the context of the crisis? Or would they write me off as someone who couldn’t stand up to pressure from the government?

The senior officers’ retreat of the Reserve Bank in late November 2008 presented a much-needed opportunity for me to open up with the senior management and speak to them candidly about my concerns and anxieties, and also about my positions vis-à-vis the government. This retreat is a standard feature on the Reserve Bank’s annual calendar when all the senior staff, from the governor down to the chief general manager, maybe about one hundred in all, go offsite for a couple of days to learn, understand, bond and rejuvenate.

I spoke without any notes which — as the Reserve Bank’s staff would learn as they got to know me better — was very uncharacteristic of me. I also spoke without any specific narrative in my mind. I levelled with them on the process leading to my appointment, on the complexity of the crisis, and my journey up the learning curve. I drew their attention to what was happening everywhere around the world — governments and central banks were coordinating as never before to fight the crisis. What was happening in India, I told them, was in tune with that pattern. It was only the special circumstances surrounding me — my background in the government and my relative ‘unknownness’ — that were fuelling these misperceptions. While I could live with the negative press, I could not live with an institution that was suspicious of me. As I concluded, I requested them to help transmit this message to the entire staff of the Reserve Bank, not all of whom were able to fully appreciate the unusual circumstances brought on by the crisis.

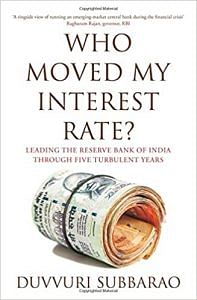

This excerpt from the book ‘Who Moved My Interest Rate?’ by Duvvuri Subbarao was published with permission from Penguin Random House.

This excerpt from the book ‘Who Moved My Interest Rate?’ by Duvvuri Subbarao was published with permission from Penguin Random House.

It is unwise to compare educational background of D Subbarao with saktikanta das. Subbarao did his B.Sc(Honours in Physics) from IIT Kgp and Masters in Physics from IIT Kanpur. Afterwards, did his Masters in Economics from Ohio State University Etc. Modern Economics speaks in Mathematics and Statistics for which skilled mathematical and statistical aptitude is necessary. For a Physicist it is very convenient to handle. P.C.Mahalonobis, the great economist and father of modern Statistics was also a Physicist.