Parvati Sharma in her book Jahangir writes about the Mughal emperor’s long tryst with alcohol and Akbar’s dismay over it.

(Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir was known as Prince Salim before his accession.)

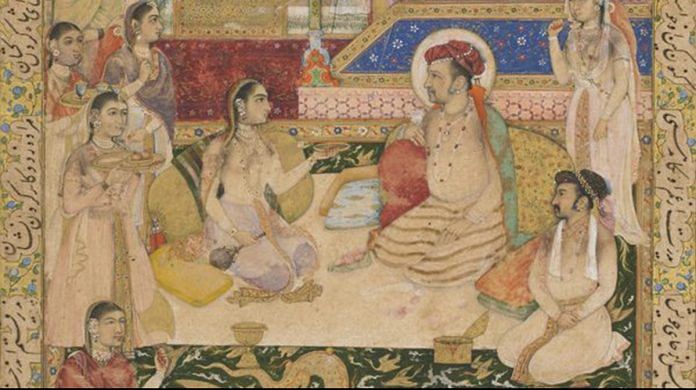

Salim had his first drink at the age emblematic of young love, eighteen, and he tells the story with fitting nostalgia (and neglects, incidentally, to relate how his first son, Khusro, was born this year, too). Ironically enough, it happened during a campaign: while the rest of Akbar’s army was busy besieging a fortress in Attock, trying to bring down some troublesome Afghans, the prince rode off on a hunt. At the end of a long day, that wonderful gunner Ustad Shah-Quli suggested wine might relieve Salim’s exhaustion. ‘Since I was young and inclined to do these things,’ Salim remembers, ‘I ordered Mahmud the water-carrier to go to Hakim Ali’s house and bring some alcoholic syrup. The physician sent a phial and a half [about 120 ml] of yellow-coloured, sweet-tasting wine in a small bottle. I drank it and I liked the feeling I got.’

‘Liked’ is not the word for it: in nine years, by his own meticulous measure, Salim had progressed from these two gulps of sweet wine to ‘twenty phials of double-distilled spirits, fourteen during the day and rest at night.’ To clarify, he goes on, that is ‘six Hindustani seers, which is equivalent to one-and-a-half Iranian maunds’.

These are the kinds of statistics that don’t really need translation. Whatever the measure, Salim was obviously drinking too much, and given the dizzyingly steep gradient of his addiction it’s very unlikely that Akbar didn’t notice. Maybe he even expected it. The Mughals were no strangers to alcoholism. Not just Salim, both his younger brothers, too, would drink excessively. The famous story of their great-grandfather Babur breaking all his wine cups in order to induce in his reluctant Central Asian amirs a righteous urge to rule the infidel – and dusty – plains of Hindustan is incomplete without the coda that he regretted it deeply, even composing a wry little rhyme on the matter: ‘While others repent and make vow to abstain / I have vowed to abstain and repentant am. However, in Babur’s case, as also in Akbar’s, the urge to drink was accompanied by an equally strong ambition to thrive. Or perhaps it was the other way around: Babur and Akbar both became kings when they were little more than children, twelve and fourteen; they knew what it was to have a precarious grip on power. And they would know that wine, while it might soothe their souls, could easily wreck their hard-earned fortunes. At every lovely sip they would have been wary of seeing their gains dissolve in their cups.

Not so the fourth-generation Mughal princes. Brought up with every luxury and comfort, all Salim had to do to helm an empire was wait – and what better way to pass the time than with a jug or six of wine?

It may be that when Akbar noticed his son’s growing addiction, he looked for an equal and counterbalancing increase in, say, his administrative zeal; but, just as Salim loved to hunt but not to battle, so he seemed to prefer the high of drink to the intoxication of rule. Or it may be that Akbar, like highly successful parents across time, was impatient for his son, the pearl he had laboured to bring to the world, to match him – and disappointed when he wouldn’t.

Whatever it was that Akbar was thinking and feeling, a kind of inchoate resentment began to corrupt the relationship between father and son during these years, and it first erupted (as such resentments often do) in the course of a family holiday.

This excerpt from Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal by Parvati Sharma has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books

This excerpt from Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal by Parvati Sharma has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books