Economic historians have tended to compare Asia’s descent into poverty with Europe’s acquisition of wealth. What this approach has tended to obscure is the ability of European imperialism to manipulate intra-Asian connections in bringing about this divergence. The acquiescence of China to unequal treaties imposed by European powers, for example, cannot be explained without reference to the British colonial conquest of India and the use of Indian opium to pay for China tea.

The trajectory of economic decline was accompanied from the mid-nineteenth century by a drastic transformation of imaginative precolonial concepts of layered sovereignty and overlapping political space to be replaced by imported ideas of unitary sovereignty and rigid borders into Europe’s Asian colonies. At the same time, colonial states monitored the movements of indentured and semi-indentured Asian labor across these borders to be set to work in mines and plantations after the formal end of slavery. Asian intermediary capital Howed into economic sectors that lay beyond the direct interest of Western colonial capitalists.

The new colonial spatiality undermined earlier forms of political accommodation of differences while enabling conditions for closer interactions among the colonized. By the 1880s, the shared sense of abjection elicited anguished intellectual critiques against Europe’s domination of an interconnected Asia from figures as diverse as the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, the Muslim anti-imperialist ideologue Jamaluddin Al-Afghani, and the Filipino patriot José Rizal.

“Eur-America had been challenging Asia for about a century,” wrote Benoy Kumar Sarkar in the preface to his 1922 book The Futurism of Young Asia. “It was not possible for Asia to accept that challenge for a long time. It is only so late as 1905 in the event at Port Arthur that Eur-America has learned how at last Asia intends to retaliate.”

In pinpointing the date marking the beginning of the Asian fightback, Sarkar considered not so much the fact of Japan’s spectacular victory over Russia as the enthusiastic celebration of this reversal of fortunes between east and west across the length and breadth of the vast continent. The intellectual fightback had preceded the politico-military one. Sarkar was on the mark, however, in calculating the European challenge to have lasted just about a hundred years. Fully aware of the historical significance of the defeat inflicted by Robert Clive on Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey way back in 1757, Sarkar was intuitively correct in seeing the decline and fall of Asia as primarily a nineteenth-century phenomenon.

The Great Divergence between Europe and Asia

The general prosperity of Asia prior to the European colonial conquest has been well documented by historians of the premodern and early modern eras. Before 1800, in Kenneth Pomeranz’s view, there was “a polycentric world with no dominant center.” In agriculture, commerce, and nonmechanized industry, the advanced regions of China and Japan compared favorably with their counterparts in England and France. Average life expectancy in the low to mid-thirties was similar in Asia and Europe around 1800, with Japan probably performing slightly better than others.

Pomeranz stresses the proximity of fossil fuel energy and the contingent availability of New World resources in explaining the European breakthrough. Prasannan Parthasarathi notes “profound similarities in political and economic institutions between the advanced regions of Europe and Asia” until the late eighteenth century. In his analysis, two pressures-the competitive challenge of Indian textiles and shortages of wood-generated the process of the British industrial leap forward. In the early nineteenth century, Latin America, especially Mexico, served as the source of silver.

The dislocations caused by the Latin American independence movements resulted in a reduction in silver and also gold production after 18il. Taking account of this global context, Man-houng Lin has claimed that “the British could not find enough silver to pay for tea and silk and ended up using opium as the medium of exchange for them.” Barring a few ex-ceptions, economic historians have typically reached consensus in identifying the decade of the 1810s as the beginning of the global economic divergence. The great divergence cannot be explained merely by reference to proximity of fossil fuel energy resources or the New World windfall for Europe. A connective history reveals the critical importance of the colonial conquest of India and the opium trail that led from India to China.

A close study of the deliberations in the British Parliament leading up to the revision of the East India Company’s charter in 1813 reveals that the decision not to pay in silver for Asian commodities was very much part of “the calculations, strategies, forms and practices of imperial rule.” Lisa Lowe has brilliantly brought to light the intimacies of four continents-America, Europe, Asia, and Africa-by showing the connections between African slave labor in the cotton fields of the US South, textile production and design in Asia, and the tea and opium trades of India and China in the making of British “free trade imperialism.”

Without political dominion over Indian territories, the English East India Company would not have been able to survive for half a century after the loss of its Indian trading monopoly in 1813. It had access to India’s land revenue, a process that had begun with its acquisition of the diwani of Bengal in 1765. Control over the land revenue of Bengal had obviated the need to bring in silver to pay for Indian textiles. From the second decade of the nineteenth century, Indian textiles lost out in world markets to the manufactures of England’s Industrial Revolution.

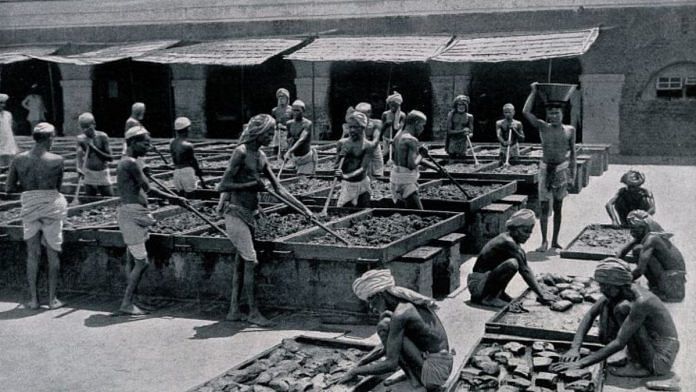

The era dominated by opium grays and indigo blues lasted in an interconnected Asia from the 1810s to the 1850s. The “indigo system” based on peasant cultivation of the blue dye under the aegis of mostly European planters provided the mechanism through which the colonial state funneled its remittances to the metropolitan center. The lucrative China tea trade was now funded by seeking to assert a government monopoly over opium cultivation in India. Despite attempts by the Qing state to restrict the influx of the deadly drug, huge illegal sales of Indian opium smuggled into China made it unnecessary for the company to bring in silver to finance their purchase of tea.

The number of chests of opium imported from India into China rose from about 4,570 in 1800-1801 to more than 40,000 chests in 1838-1839 on the eve of the outbreak of the First Opium War.” The East India Company had the dubious reputation of being by far the largest corporate drug dealer in the world during the first half of the nineteenth century. Its ruthless resort to cruelty and coercion was tempered by a search for complicity among the colonized. The company’s effective monopoly on opium cultivation did not extend beyond the Gangetic plain where the Patna and Benares varieties were processed in a factory at Ghazipur.

Private traders sourced the drug from Malwa in central India and initially exported the commodity from the Portuguese port of Daman. Not to be cut out of the profits from drug trafficking, the British allowed Malwa opium into Bombay, which soon acquired the appellation of “opium city.”

The formal abolition of slavery coincided with the extinguishing of the company’s monopoly to trade with China through the revision of the Charter Act in 1833. Several ships that transported slaves were now redeployed to carry opium. The schooner Psyche and the brigs Ann and Kelpie had been slavers but were in the late 1830s engaged in the opium trade. The connection stretched from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. The Boston merchant Bennet Forbes sent the Lintin out on opium runs from 1830 and then commissioned the clipper Rose to work on the China coast with Russell and Company.

The Qing Empire observed these developments with increasing disquiet. Once the local Chinese authorities led by the special high commissioner in Canton, Lin Zexu, took the drastic step in June 1839 of dumping more than 20,000 chests of illegal opium into the sea, war became inevi-table. With some $6 million or 2.5 million pounds sterling worth of contraband sunk in saltwater, London decided to send an expeditionary force, which arrived in June 1840. By the time this war ended two years later, the British took possession of Hong Kong and won concessions in five more treaty ports on the east coast— the first major step in what they reckoned was the opening up of China.

This excerpt from ‘Asia after Europe: Imagining a Continent in the Long Twentieth Century’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘Asia after Europe: Imagining a Continent in the Long Twentieth Century’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

its well known in history that the british are known for their double standards, they can never be friends with anyone, especially Muslims.. at one side they support muslims in today’s middle east to fight against the Ottoman empire and Calipha, making so called kings in saudi and other nearby nations and behind the scenes bringing in zionist terrorists into palestinian lands… … 1757 war to kick out british by siraj ud dawla was 1st step towards the british cunningness wickedness