At Chengdu, we put up at a homestay. The owner cautioned us, saying, ‘The entrance door to the apartment complex closes at 11 in the night. If you want to enter after that, you have to knock and the doorman will come. You pay him 2 yuan. Then he will open the door.’

A unique Chinese solution!

I always enjoy the first day of a trip—settling into another rhythm, another life, missing my toothbrush at its familiar place. Our window overlooked the People’s Park, which was bordered by one of the busiest thoroughfares in Chengdu. As Lobo caught up on her sleep, I spent the first morning just watching this street. An old couple was crossing the street and when the man attempted to hold the lady’s hand, she angrily snatched it away. A sharp-suited man was walking with a large broom he had just bought. Children hopped around in padded clothing. Migrant men from Xinjiang, obvious from their appearance, lazily manoeuvred their carts loaded with memories from their arid land, colourful small mounds of dried fruits.

That day, we decided to relax since our high-altitude hardship was soon to follow.

We visited a tea-house, a famed Chengdu institution where patrons could leisurely spend a whole day with a cup of decent tea for 15 to 20 yuan. As expected, half the floor in the tea-house had been covered in spit, spitting being a great Chinese pastime. Ear-cleaners in traditional uniforms moved around clinking their tongs, displaying an array of fine-pointed equipment held like chopsticks between their fingers. To give Lobo a nice photo-op, I engaged Mr Chin. Why not have clean ears before an adventure?

Mr Chin congratulated me on my decision, ‘You are a smart man. You are going for a long adventure to a tough area. Cleaning your ears helps clear up your mind before that.’

Pleased with the advice, I enquired more about Mr Chin’s career. ‘I have been doing this for over 20 years,’ Mr Chin said. ‘At this same tea-house! We are like shareholders here because if we don’t work here, no one will come to this tea-house.’

He charged 20 yuan for ear-cleaning while offering top-up services.‘On a bad day, I get five customers. On my best day, I get 10.’

He convinced Lobo too to add up to his numbers for the day. As he started cleaning her ears, he said, ‘Girls rarely ask for our service because they are too shy to be seen in public like this. But you are a good person.’As Mr Chin departed, he said, ‘The strangest thing I have picked from someone’s ears is a silkworm.’

Also read: Indian tourists are finally out. But there’s a bigger headache than coronavirus — red tape

Soon, I was hungry and what better place to find vegetarian food than at the Manjushri temple, one of the oldest in Chengdu, also famed for its vegetarian buffet? The approach to the temple was lined with beggars, the disabled and the mentally unsound, hoping for alms, some shouting out their grievances and blessings to patrons over loudspeakers. Ignoring their pleas, I went straight for the vegetarian buffet where a notice said that there was a 5-yuan refund if no food was wasted. That set my mind into a frenzy. How would I retrieve that 5 yuan? Instead of enjoying the food for which I had already spent 35 yuan, I conjured scheme after scheme to make my plate as well as Lobo’s look clean. Eventually, I played a trick, cleaning up our plates in the trash bin just when no one was looking. Tense, I walked up to the nun manning the cash counter, and once I got the 10 yuan back, I achieved nirvana.

Enlightened, I walked inside the temple to check if there was anything left to see. A signing-up booth for monks caught my attention. I looked through the register and noted that 10 people had already signed up for the initiation ceremony for the next day. A young woman asked the two elderly ladies at the counter, ‘If I sign up, will I never be able to marry?’

‘No problem at all,’ came the response in unison from the two ever-smiling ladies, ‘You can choose to be one of those monks who stay within the family.’ Our nun-wannabe was still not convinced, ‘Will this show in my documents?’ ‘Not at all,’ the duo replied in unison, ‘In China, every individual has the full freedom to practise religion.’

Just before she was about to put pen to paper, another question sprang up in her mind, ‘Hold on,’ she looked alarmed. ‘Will I have to pay?’

‘Not at all,’ came the synchronized reply, ‘Not only is it free, we will also give you a mantra book and a rosary for free.’

At that very moment, another name got added to the queue for a Buddhist heaven.

To make a soft landing into Tibetan culture, we spent the evening at Chengdu’s Tibetan quarters. Chengdu is the largest Tibetan city outside of the Qinghai–Tibetan plateau with more than 30,000 resident Tibetans and a floating Tibetan population of 150,000 to 200,000.1 The streets of ‘Little Lhasa’ had its fair share of ‘Chinese Dream’ posters. On both sides of this ‘Parkour Street’ were shops selling all things Tibetans need—incense sticks, prayer flags, thankha posters, monk robes and handheld prayer wheels. There were beads, beads and more beads hung up densely from the shop walls, spread out in heaps on the pavement by upstart sellers, attracting robed monks looking for a prayer counter and teenage girls looking for a cheap fashion fix. Some shops were galleries of bodhisattva statues. They came in all sizes—from palmtops to giants suitable for the most ambitious temple halls—all gilded, their eyes casting that piercing glance of Tibetan Buddhism.

As we walked along the Tibetan quarter, we spotted a nomad getting a haircut, with his locks covering the entire floor. A middle-aged Tibetan couple was sitting on the curb stones by the road, looking lovingly at each other although the man kept counting prayer beads all the while. At a Tibetan bookshop, the entrance was lined up with books on Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, and government brochures on how to obtain a passport, arguably a difficult endeavour for any Tibetan. The police presence in this area was heavy. With so many Tibetans around, the authorities perhaps feared that anything could happen anytime. But to keep calm, people set up impromptu stalls on the streets as soon as the sun set, selling yogurt made of yak milk.

Also read: India’s adventure tourism circuit with Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka can boost the sector

I prepared myself in another way for the trip, by getting my hair shaved off at a Chengdu salon. I attracted quite a crowd at the salon as the staff and some passers-by surrounded me to witness what surprises my scalp would reveal once it was denuded of hair. When nothing worthy of gossip appeared, I tried to compensate for their time by entertaining them with my wisdom.

‘I do two things every time I go for long trips,’ I said to the audience through Lobo, my translator. ‘Number one, I always shave off my hair and number two, I do not shave my face for the entire trip.’

‘Why so?’ asked the young hairdresser. ‘Shouldn’t you grow your hair long instead? It will be very cold where you are going.’

‘That doesn’t matter,’ I said. ‘It’s simple Yin and Yang. Shave the scalp, grow the beard.’ The cashier intervened, ‘It must be some kind of lucky charm for him.’

‘No,’ I objected. ‘It is a matter of principles. And what is a man without principles?’ ‘We don’t understand,’ said the people in the crowd as they dispersed, looking puzzled.

For dinner, we met Lobo’s friend and her partner at the Gesar Kitchen, an apt choice since we were soon going to tread where the legendary King Gesar once had. The king of the ancient Tibetan Ling kingdom, Gesar is the hero of the epic named after him, the greatest work of Tibetan literature, probably composed in A.D. 200. Lobo’s friends, a rather congenial couple, warned us about what to avoid during our trip.

They cautioned, ‘Don’t drink water from any of the streams—they contain a parasite that grows within the body and there is no cure for the condition it causes; don’t ask the price of any item unless you really want to buy it. You can negotiate and bargain, but walking out after asking about the price is considered very rude; beware of Tibetan dogs. Always carry some stones in your pockets and a stick. These dogs can chase you for up to 3 km, so always maintain a stock of 3 kg of stones. Stock up at Kangding, as you can get the right sizes there.’

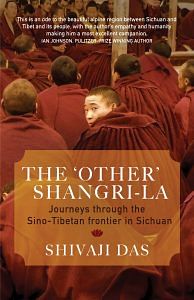

This excerpt from The Other Shangri-La: Journeys Through The Sino-Tibetan Frontier in Sichuan by Shivaji Das has been published with permission from Konark Publishers.

This excerpt from The Other Shangri-La: Journeys Through The Sino-Tibetan Frontier in Sichuan by Shivaji Das has been published with permission from Konark Publishers.

COMMENTS