Lahore, with a long history of communal harmony and accommodation, escaped the brunt of this cycle of bloodshed; but the poison seed had been sown. As the uncertainty, initially, of the political terms of Independence, and subsequently of the territorial award to the two new entities, sharpened, daily demonstrations in the city by political formations, drawn one against the other on communal lines, raised tensions to a pitch. Low grade violence was a quotidian event, though it was yet to spill over into a mass conflagration.

In February 1947, however, all this was far away from the tranquil milieu of Model Town, a fresh, sprawling, ‘garden city’ developed across nearly 2,000 acres some ten kilometres south of the old city, in the early 1940s. This was a genteel, upper class suburb, populated by the educated elite – judges, bureaucrats, professors, politicians, engineers – and the wealthy of Lahore. In one of the colonnaded bungalows, surrounded by rambling lawns and gardens, lived Rachpal Singh Gill, an alumnus of King’s College, London, a civil engineer in the Irrigation Branch, who would go on to distinguish himself as one of Independent India’s great Dam builders, working on key projects including the Bhakra Nangal Hydro Power Complex.

His twelve-year old son, Kanwar Pal Singh Gill was home, on his long winter vacation from boarding school at St. Vincent School, Mussoorie. At this blissful age in the quiet, plush, but rather isolated environment of Model Town, Kanwar Pal had little interest in the tumultuous, potentially calamitous, politics that was shaping up in the Old City. His greatest challenge was to find sufficiently amusing ways to pass his time – not an easy task for a boy without any companions of his own age in the neighbourhood. His cycle was his best mate, and he spent many hours tearing around the empty roads of the sparsely housed colony. Climbing and falling out of trees was another useful diversion, given the added excitement of a mild and unsympathetic cuffing from his mother, Amrit Kaur, if he managed to hurt himself in the process.

Back home at Model Town, some little amusement could also be extracted out of teasing his five- year old sister, Nina, for whom he had the contemptuous, protective, affection of a twelve-year old for a younger sibling. His elder sister, Guddi, was back at her hostel at the Sir Ganga Ram School in Lahore, since her shorter winter vacations were over by this time. There were also, always, books to be read – Kanwar Pal’s lifelong friends. In all, it was a pleasant, mildly soporific, time of innocence.

It was a chilly winter evening when Kanwar Pal was summoned by his mother. Amrit Kaur, no more than 29 years old at this time, was a strong, self-possessed woman, deeply religious, something of a disciplinarian, and not very tolerant of the harmless mischief Kanwar Pal often wrought. The boy entered the room with trepidation, half-resentful at having a good read interrupted, at the same time, raking his memory over what may have got him into trouble this time around. He could think of no proximate cause, particularly when he saw his mother’s sombre countenance. This is bad, he thought, still worrying about what he could have done to provoke his mother’s apparently extraordinary ire.

Also read: How former Punjab DGP KPS Gill approached & hit back at terror, recalls new book

He noticed, then, two swords lying on the table before her. She drew him close and explained, quietly, that difficult times were around them; there was violence and bloodshed, and more would likely come; that the villages that lay beyond Model Town – Kanwar Pal was aware of these only as a source of a regular supply of milk to the house, and the occasional odd-job men who were called in to work – were ‘Muslim’; and that it was possible that there would be an attack from this quarter on the overwhelmingly Hindu and Sikh Model Town. She handed the two swords over to the boy. You must keep these beside you all the time, even when you sleep, she said. If they come, you will fight. If you think they will prevail, you must first kill your younger sister so that she does not fall into their hands, and then you must return and fight to the end.

“Suddenly,” K.P.S. Gill recalled, more than six-and-a-half decades later, “my mind became clear. What I was being told was not an appeal or exhortation; it was a command; and I accepted it as such. When I think back, I am surprised at the matter-of-fact way in which I accepted the situation. There was no doubt in my mind of what I would have to do… what I would do… if the attackers came.”

Over the coming weeks, the swords were always with the young Kanwar Pal, and his mind raced over the many images of the dread duty that had been conferred on him. He held the swords aloft, touched the cold steel of the blade, imagined the fight that was to come, and felt no fear. It was, however, the thought of taking his young sister’s life that troubled him greatly. Abruptly, his nebulous feelings towards the younger child crystallised, and he became aware of his deep fondness for her. But he knew he would have to steel himself for the terrible task when the time came.

On the face of it, in the weeks that followed, little changed. His father would go to office every day and return to his routines each evening. The quotidian rituals of the household continued as before. But Kanwar Pal’s games were dampened; the cycle lay neglected, leaning against a veranda wall; the tree-climbing was forgotten; the books failed to hold his attention. Around him, much that he had missed over the past months acquired new significance. The quiet conversations, away from the children’s earshot, between the elders – his parents, visitors, servants; the occasional words he picked up – riots, stabbing, Jinnah, Muslim League, Hindu Mahasabha, Nehru, Gandhi, Noakhali, Naara-e- Takbeer, Har Har Mahadev… the spectral tonality of faraway events that were changing their lives.

Through all this, there was a sense of rising anger at the sheer injustice of the threatened violence. What could justify the murder of children, of women, of innocents? How could the lives of entire communities be forfeit, merely because they were a minority in a particular area? How could vast numbers of people be forced to live under such intolerable peril, merely by the fact of their religious identity?

The Partition and the disorders that preceded it were a monstrous time, and they inflicted a monstrous choice on a twelve-year old – among millions of others – to possibly have to kill his own five year old sister, and then himself embrace death. That age, and that awful dilemma, passed quickly for Kanwar Pal; but the ages that followed were to be, for him, no less afflicted by dreadful choices. Indeed, for Gill, these choices have been far more numerous than for most people. “I have,” he recalled gravely, “seen more death in my life than anyone I know.” Through all this, however, the memory of Partition, his intense sense of outrage at the appalling task he was asked to perform, and an enduring sense of the vulnerabilities of minorities and of the weak, guided K.P.S. Gill through much of his life. “It taught me,” he said, “that no human being should be subjected to this sort of choice, to such fears of mob attack without any protection from any quarter. This is a feeling that reasserts itself whenever a minority was brought under attack anywhere in my jurisdiction. Through my service career I have believed that minorities, the weak, the vulnerable, have to be protected at all costs, irrespective of their identities or the circumstances of their misfortune.”

Eventually, the young Kanwar Pal’s swords were never put to use. He was sent back to school at the end of his vacations, just days before the carnage of Partition commenced. Lahore was to be devastated, cleansed of almost all its Hindus. In Model Town, of 1,300 bungalows, 1,100 that were occupied by Hindus and Sikhs were vacated, their residents forced across a new and bloody border, into a truncated India. Given the sheer ferocity of the butchery in Lahore, however, Rachpal Singh and his family were fortunate. It was his Muslim friends who formed a protective convoy and escorted the family – with many relatives, near and distant, and others who joined the motorcade – to the border, and to safety.

Also read: Why Partap Singh Kairon, man behind Punjab’s industrial and agricultural growth, was killed

That moment in Lahore was a coming of age for the young Kanwar Pal. It shaped his entire future, not only in the sense of his worldview, but at many and often subtle levels. The calm courage of his mother made her the most significant influence of his life, though he was to lose the protective embrace of her sheer presence just a few years later. The closeness and interdependence and understanding that permeates the family unit was brought home in those long hours, when each one in that Bungalow in Model Town, Lahore, went about his or her own pursuits and activities, but all were bound together under the threatening pall of an imminent attack, forced to an unspoken acknowledgement of the strength of their sentiments, each for the other.

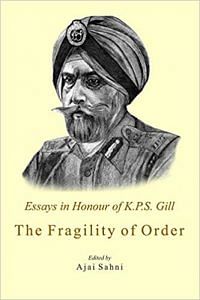

This excerpt from The Fragility of Order: Essays in Honour of K.P.S. Gill by Ajai Sahni has been published with permission from Kautilya Books.

This excerpt from The Fragility of Order: Essays in Honour of K.P.S. Gill by Ajai Sahni has been published with permission from Kautilya Books.

Father figure for me . Lucky enough to met Gill Saab in person over tea.

We as nation and specially Hindus of Punjab are always indebted to Gill Saab

My regards

Have a tremendous amount of respect for K.P.S Gill! He always took the bull by the horn and never shirked duty! Definitely the svior of Punjab and India!

Mr K.P.S. Gill Without Doubt A Towering Figure and One Of The Finest Personalitys Of the 20th Century.

Great son of India, KPG Gill. A thorough professional, courageous, clever and gritty. Savior of the Punjab, pulled it out of the depths of despair. A true leader. They ought to have honored him with the Bharat Ratna, not the political stooges and toadies who usually seem to beget that honor.