Located in the heart of New York City, Barnard College has a long history of advancing higher education for women. It was founded in 1889 in response to Columbia University’s policy of not admitting women students. Columbia’s position against women was not unusual at the time—most of the other elite Ivy League universities considered women unworthy of admission too. What was more unusual was that Frederick Barnard, then President of Columbia, was a supporter of equal rights to education for women. He advocated for coeducational programs at the university but was unsuccessful in convincing the Board of Trustees to go where no other Ivy League school had gone before. Nevertheless, he did succeed in creating the Columbia Collegiate Course for Women, a program of study that allowed women to obtain an undergraduate degree despite not being allowed to take classes at his own institution.

One of the women who enrolled in the program, Annie Nathan Meyer, was so frustrated at being barred from attending lectures and working in the labs at Columbia that she took up the cause of creating the first women’s college in New York City. Meyer was just the right person to lead the effort, realizing the need for public support, substantial funding, as well as university backing to make her dream a reality. In an article published in the Nation, she shrewdly argued that a city like New York must have a women’s college to maintain its reputation in the world. At the same time, she invited powerful and wealthy New Yorkers to join a committee to support the funding of the College. And in another smart move, she gained the support of Columbia University’s board of trustees by proposing to name the new college after Barnard, who had recently died.

Annie Meyer saw her vision come to fruition in 1889 when Barnard College threw open its doors just down the road from Columbia. Initially operating from a rented building, generous gifts from wealthy women quickly led to the building of a new campus and an increase in enrollment and courses offered. Barnard soon earned its place among six other distinguished American women’s colleges. (Mount Holyoke was the first of these to be founded in 1837, followed by Vassar, Wellesley, Smith, Radcliffe, and Bryn Mawr.) With the addition of Barnard, the Seven Sisters, as they were nicknamed after the stars in Pleiades, collectively became a shining constellation of hope and education for women across the country.

By 1904, the physics department at Barnard, which consisted of a single faculty member, Professor Margaret Maltby, was looking to expand. Qualified women professors in physics were not so easy to find, but Barnard hit the jackpot with the person they hired. Harriet Brooks had obtained a master’s degree in mathematics and physics at McGill University in Canada in 1901, under the supervision of the future Nobel Prize winner Ernest Rutherford. Brooks came highly recommended by Rutherford and the President of McGill, and she more than lived up to expectations. The following year, Barnard renewed her contract with a 10 percent raise in her salary of $1,000. In 1906, Brooks once again received a contract renewal, but her circumstances were about to change. She wrote to the Dean of the College, Laura Gill, to say that she was going to be married in the summer of 1907 and asking if this would affect her employment. Brooks had already spoken to her colleague Margaret Maltby, who did not think the marriage was an issue. Dean Gill had a different opinion. Marriage would “end your official relationship with the college,” she informed Brooks. So much for the vaunted feminism of the Seven Sisters.

Brooks wrote a fiery response to the Dean, arguing that her new relationship would help rather than hinder her performance and that she would resign if at any point her marriage interfered with her duties. She felt that it was her responsibility to show that “a woman has a right to the practice of her profession and cannot be condemned to abandon it merely because she marries.” Furthermore, she called out the hypocrisy of women’s colleges for supporting women’s education but not their right to a professional career after marriage. “I cannot conceive how women’s colleges, inviting and encouraging women to enter professions can be justly founded or maintained denying such a principle.”

While it was common at that time to expect women to give up their careers after marriage, Barnard was after all an institution that was founded with the specific goal of advancing women’s rights. How could a reputed school for women be so unyielding and still hope to maintain its reputation? In fact, it was the school’s reputation that the Dean and the Board of Trustees believed was put at risk by the impending marriage. In her response to Brooks’s objections, Dean Gill noted that the trustees (many of whom were men) assumed that a woman’s primary focus is and should be homemaking. Balancing the burden of two full-time professions was not possible, and hence not good for the College. Gill concluded that maintaining the “dignity of the woman’s place in the home” as well as the reputation of the College required Brooks to resign her position.

Balancing the full-time demands of homemaking and the rigors of an academic career in physics (or any field, for that matter) was a binary problem for which Dean Gill and the trustees could see only one, unchangeable solution. Ironically, the leaders of an institution built to promote innovative thinking seemed unable to think outside the box of their times. Brooks’s colleague, Professor Maltby, wrote to Dean Gill, pleading for an exception to be made, noting that Brooks was an excellent physicist and teacher and that she knew of no other woman qualified enough to take her place. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, although Maltby was right about Brooks’s excellence and the loss to Barnard College. In firing her, Barnard was letting go of a woman described by Rutherford as second only to the legendary Marie Curie. Even before she arrived at Barnard, Harriet Brooks had already transformed physics.

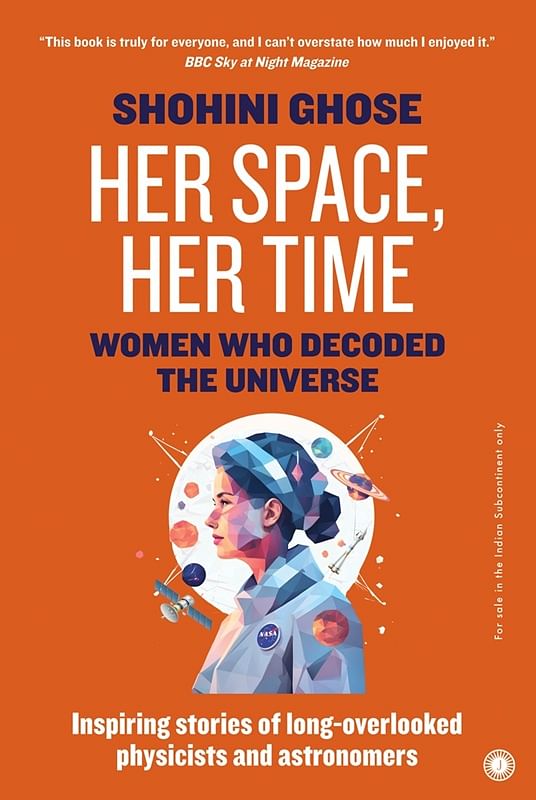

This excerpt from Her Space, Her Time: Women Who Decoded The Universe by Shohini Ghose has been published with permission from Jaico Books.

This excerpt from Her Space, Her Time: Women Who Decoded The Universe by Shohini Ghose has been published with permission from Jaico Books.