Depending on who you ask, I am either fiercely feminist or incredibly toxic. There seems to be a very thin line between fierce and toxic in feminist circles these days (I have been called both at various points, and honestly neither ever seemed to quite fit), but one of the things I have noticed about the term fierce is that it carries its own highly specialized baggage. The women most likely to be called fierce are also those most likely to be facing the greatest social risks.

The same tired tropes always end up being trotted out. The Angry Black Woman, the Sassy Latina, and so on. What we ignore is that those narratives inform how we view the women we claim to venerate. We think of Beyoncé’s feminism as fierce right up until she turns out to be a human being who loves her spouse more than the idea of the Strong Independent Woman Who Doesn’t Need a Man. We adore Serena Williams until she’s visibly angry while challenging a system that continually harasses her with drug tests and questionable calls from line judges. Then we think she’s too angry and needs to calm down. They’re warriors, but apparently not the right kind of warriors.

Yet their careers and their lives are amazing examples of the power to succeed as women in male-dominated industries. There’s something so wonderful about having the power to come from working-class roots to acquire not just fame and fortune, but the power to shape the culture. They give young Black women the power to delight in beauty and sexuality by having the kinds of careers that dominate mainstream media while still championing feminism as a powerful force for the good of girls. Yet when they have the audacity to not only claim feminism, but feel like they get to dictate and direct the way that they engage with it, there’s some sense that suddenly they are less qualified because they used their bodies— much-maligned, much-analyzed bodies— to achieve those careers. Critics still question their idea of female empowerment.

Also read: Feminism hasn’t sold-out, it’s only using corporate spaces to mobilise support

They want them to wear more clothes, to not be so strong or so sexy, or to not be so cheerfully, enthusiastically unconcerned with hitting a checklist of “appropriate” feminist milestones. But fiercely fighting your way past the boundaries that white supremacy might set isn’t for the faint of heart. We know, after all, that well-behaved women don’t make history.

Still, as the criticism of both Beyoncé and Serena ramped up, as the backlash for them choosing to go their own way spread out to criticism not just of their careers, but of their personal lives, even of their children, it was clear that being so fierce had consequences. And while those two women have the resources and the networks required to insulate themselves, the average woman fighting against the patriarchy is more likely to be far less privileged. Yet the demands that the risks be taken by those without the insulation of racial privilege never abate. Instead the narrative is one that lauds the courage of those who do take the risks, with very little discussion of the possible aftermath. Whether it is being outspoken about police brutality, harassment, and sexual assault in politics, entertainment, tech, or other industries, too often those who speak out are positioned more as sacrifices than saviors. When the seemingly inevitable backlash complete with harassment and death threats starts, some feminists will speak up; many will simply suggest contacting the police or the FBI, but they won’t offer anything else. And if anyone brings up the lack of meaningful support for victims, the conversation is quickly shifted to center on those who didn’t take the risk.

In my experience, when I have been targeted or other Black women have been the primary targets of harassment, Black women have had to back each other up on social media.

Also read: One year after India’s big #MeToo wave, a reality check

Whether the reason for the harassment is being pro-choice, a critique of the political choices of a GOP spokesperson, or something like what has happened to professors like Anthea Butler, Eve Ewing, and other Black academics, they are at best lauded for their fierceness from a distance by white feminist writers. More often they are ignored, or as has been the case with House representative Ilhan Omar, they are targets of white feminists like Chelsea Clinton, until the rhetoric spills over into actual physical violence. Suddenly the same women who adore fierceness, who celebrate ideals like speaking truth to power, are all about their own personal fragility. After all, being fierce has its consequences. And besides, it’s not like they’re the police. They aren’t responsible for protecting anyone, for helping anyone access safety, or for connecting anyone with resources. Well, not anyone inconvenient, anyway. Not when there was a carceral solution that they could rely on at their fingertips.

We know that carceral feminism (a reliance on policing, prosecution, and imprisonment to resolve gendered or sexual violence) is most likely to be used against women who fight back. Particularly women of color. The state responds to public concerns around sexual violence by re-traumatizing victims. It rarely offers them anything approaching justice. The carceral impulse also informs how feminism responds to victims before, during, and after they attempt to press charges or otherwise combat the patriarchy.

What has arisen repeatedly in feminism is a tendency to assume that once victims have gone to the state, their needs are all met. This is especially obvious in the responses to online harassment. While many feminists have no problem arguing for criminalizing the behavior, they are light on ways to safeguard those experiencing it. Because of the impact of a carceral approach, we see a framework that restricts feminist horizons to structures that expect the individual to fight rather than the collective.

This form of individualist feminism relies on the idea that an empowered woman can do anything. It ignores the economic and racial realities that some face. What does individualist feminism look like in practice? While we stand on the sidelines cheering women on, largely there has been minimal collective efforts to fight oppression across multiple identities. We ignore the fact that the same structures affect us all (albeit differently), and we rely on the myths of strength rather than on any understanding of what it means to work together. It doesn’t help that when welfare reform was enacted, politicians ignored the fact that victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and so on might not be able to go back to work immediately or at all. Without funding for public housing and other social safety nets, low-income survivors in particular found themselves “helped” right out of any measure of stability.

Also read: Acknowledge your privilege, but don’t discount your struggle, says rapper Sofia Ashraf

While we laud the strength of those who fight back, this sometimes leads to victims being arrested for defending themselves. This is especially true in the case of sex workers, victims of domestic violence, and others who find themselves squeezed by the system that prioritizes imprisoning them over protecting them.

Equality is great, but equity is better precisely because the emotional validation someone with financial security and the insulation of privilege might need is nearly useless for someone without those things. It’s the Strong Black Woman problem writ large enough to include other communities, though still most likely to impact Black and Brown women. We expect marginalized voices to ring out no matter what obstacles they face, and then we penalize them for not saying the right thing in the right way.

We need to understand that sometimes the fiercest warriors need care and kindness. We can’t be afraid of their anger or their willingness to shout. We love that fierce energy in the moment, but we need to embrace it across time. We need to shift our ideas of who deserves support and move away from the idea that after the case everything is fixed.

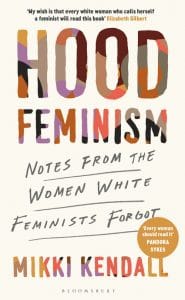

The Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women White Feminists Forgot by Mikki Kendall has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

The Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women White Feminists Forgot by Mikki Kendall has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

The same Muslim women never come on the street against triple talaq and halala marriage which is rampant among Muslims. But they do come against CAA which does not affect Indian Muslims. These demonstrations are sponsored ones.