New Delhi: October 2018 wasn’t the country’s first brush with speaking up about sexual abuse. In 2017, a crowd-sourced list now called LoSHA (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia) created ripples in academic circles. And in the wake of the news about Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s sexual crimes, the words “Me Too” were all over social media, with women everywhere posting them in solidarity.

Those rumblings gave way to a powerful movement last year, when hundreds of survivors of alleged sexual assault and misconduct broke their silence. They took to social media and named names. Politicians, comedians, actors and directors, journalists, advertising professionals, award-winning authors and artists — skeletons were tumbling out.

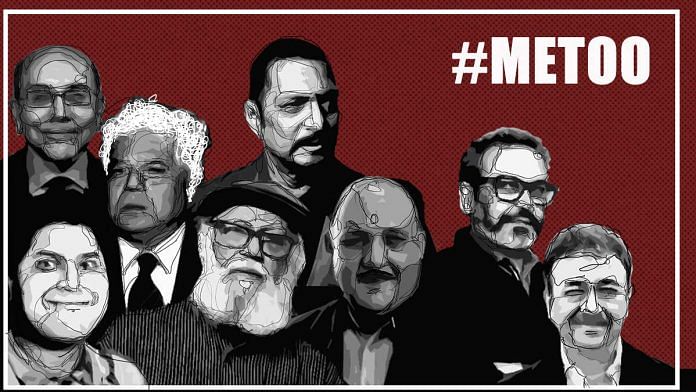

Nana Patekar. Alok Nath. M.J. Akbar. Suhel Seth. Jatin Das. Kiran Nagarkar. These are only some of the men who were named and shamed last year when the #MeToo movement swept across India. After decades of silence, sexual harassment at the workplace was acknowledged and talked about openly. The conversations that took place in whispers were suddenly loud and clear. It felt momentous and there was hope things would now change.

But, today, that hope seems to have dissipated for many who were at the forefront of #MeToo.

Several of the women and men who had spoken up last year told ThePrint that while the movement did stir things up, it did not lead to any meaningful and long-lasting change. Most of the accused, they said, have got away with a mere rap on the knuckles.

Others though say that change is creeping in, albeit very slowly – at workplaces, in movie and comedy show scripts and everyday interactions and conversations. Either way, the post-#MeToo India is one where talking about sexual harassment isn’t a taboo and that in itself is a beginning.

Powerful names named

In September 2018, former actor Tanushree Dutta alleged that actor Nana Patekar sexually harassed her on the sets of Horn Ok Pleassss in 2008.

A slew of powerful names followed, including actor Alok Nath, who was accused of rape by filmmaker Vinta Nanda. Multiple other women accused him of abuse as well, including actors Sandhya Mridul, Navneet Nishan and Amyra Dastur, and singer Sona Mohapatra.

According to reports, police might soon file a closure report in the Nanda case, citing a lack of evidence as the allegations go back to the 1990s. Meanwhile, Nath continues to do movies — including a film on sexual harassment, Main Bhi (Me Too), in which he’ll play a judge.

Casting director Tess Joseph says CINTAA (the Cine & TV Artists Association) was the only organisation that took a stand on Alok Nath.

“It banned him, even though Vinta wasn’t part of CINTAA, but what’s the point? CINTAA has no power as it’s not mandatory for an artiste to be a member, so Alok Nath can be banned but still get work,” adds Joseph, who had herself named Malayalam director and CPI (M) MLA Mukesh.

Director Rajkumar Hirani, accused of sexual assault, was invited as jury head for the Malaysia International Film Festival this May. He was also given a special award at the recently concluded IIFA ceremony, for 3 Idiots — a movie whose defining comic scene is a rape joke. Last year, Aamir Khan stepped away from Moghul as director Subhash Kapoor had been accused of molestation by actor Geetika Tyagi. But he’s now back on the project because “he felt guilty about taking away a man’s right to earn a living”.

“Everyone has empathy for the men who, in most cases, aren’t even losing their jobs, but what about empathy for the women?” asks Mohapatra.

It’s not just in the movies. Scene and Herd, an Instagram account that says it outs predators in the art world, named more than 60 artists, including Subodh Gupta, Riyas Komu and Binoy Varghese. The team behind the account says there might have been some initial kneejerk reactions but soon enough, all was back to normal. Artist Jatin Das, for example, was named by at least 13 women, but showed his work at two Delhi galleries this March.

Late novelist Kiran Nagarkar, accused by multiple women, had his last book published by Juggernaut Books, after Penguin Random House cancelled the contract.

Branding professional Suhel Seth was accused by at least six women of harassment and assault. A few days ago, Inkpot India Conclave announced that Seth would be one of their “literary torchbearers” at an event on 18 November. Following an uproar, the organisers announced his withdrawal “owing to his travel commitments and impending fatherhood”.

Oh! Suhel Seth is back. And back as a "literary torchbearer" now.#MeToo #Metooindia pic.twitter.com/5XWLv5Bpgx

— Abhishek Dey (@abhishekdey04) September 29, 2019

Owing to his travel commitments and his impending fatherhood @suhelseth would not be at any public speaking engagement and hence has expressed his inability to be at @InkpotConclave

— Inkpot India Conclave (@InkpotConclave) October 1, 2019

BJP MP and former editor M.J. Akbar, accused of harassment and assault by at least 20 women and rape by one, resigned as minister of state for external affairs last year. But just over a month later, a column by him was published in Hindustan Times. In a statement to ThePrint, Hindustan Times said, “We believe that allegations of that kind are different from journalistic competence of the person concerned.”

The Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi was accused of sexual harassment by a former employee of the Supreme Court in April, who stated she was fired when she objected. He was cleared of all allegations in an investigation that was seen as having failed due process.

Also read: #MeToo movement shook Bollywood status quo, hasn’t fizzled out yet: Tisca Chopra

Lawsuits and lack of work for survivors

Things haven’t been quite as smooth for those who spoke up. Less than a week after Nanda’s allegations surfaced, Nath filed a defamation case against her.

Just recently, Subodh Gupta too filed a defamation case, in which the Delhi High Court ordered Facebook, Instagram’s parent company, to reveal the identity of Scene and Herd’s administrator. Facebook and Google have also been told to take down the content against Gupta.

India Today journalist Gaurav Sawant, movie director Susi Ganeshan and actor Arjun Sarja have all filed defamation suits against those who named them. And singer Chinmayi Sripada claimed work opportunities started drying up after she named lyricist Vairamuthu and became a vocal supporter of the #MeToo movement.

Speaking about sexual misconduct, Delhi-based criminal lawyer Ajay Verma says a complainant has bleak chances of successfully proving charges from an incident that occurred years earlier.

“Section 468 of the Criminal Prosecution Code bars the magistrate from taking cognisance of an offence under Section 509 of IPC (word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman) beyond one year. Under the PoSH Act [Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013], there is a period of limitation of three months,” he explains. “It can be extended but not later than another three months.”

Advocate Geeta Luthra, Akbar’s lead counsel in his criminal defamation case against journalist Priya Ramani, says, “Suppose somebody says you were in Connaught Place on 20 December 1984. How do I answer this? I might not even remember it. The person being accused may not remember what happened decades ago, so how will they defend themselves? It is with this perspective that there is a statute of limitation in most cases and the court says that the cause of action should be in present.”

Kolkata-based lawyer Kaushik Gupta says as a lawyer, he’s “strongly against the witch-hunt that the due process of law is not being followed”.

The issue, he says, is many of us do not know the due process. He says that the judicial system is “not very friendly”, but adds that “it (#MeToo) shouldn’t have been done because it diluted the entire thing. Has it stopped sexual harassment? Has it even brought down sexual harassment?”

Seeing the mirror

Comedian Abhineet Mishra believes the #MeToo movement has helped the industry distinguish between genuine feminists and those who create “woke” content just for the sake of it.

“Many male comedians run their jokes past us (female comedians) now to ask if it’s funny or offensive,” comedian Neeti Palta says. “I am called to a lot of corporate shows where I am asked to talk about diversity policies and gender-sensitisation as part of my sketch.”

In the news media, the flood of allegations and urgency of the movement triggered several questions about the way the allegations were handled. Garusha Katoch, one of the women who named Jatin Das, recounts, “Some media houses didn’t even speak to you, but just reported on it. A couple of these channels even went to my Facebook without my permission, dug up all these images of me, and made really distasteful videos.”

Journalist Ankur Pathak of Huffington Post India, explains, “Covering sexual crimes in the way that we have is unprecedented.” The scale, speed and sensitivity required at the peak of #MeToo was not something Indian media had a blueprint for.

Sandhya Menon, a Bengaluru-based journalist who herself named two editors — K.R. Sreenivas and Gautam Adhikari — believes there was “a complete failure of the media to go beyond accusations and look at the cultural context”.

“This should have been a beat in this last year,” she adds.

In Bollywood, the backlash seems to be against those who spoke up, not the accused. Apart from the upcoming Main Bhi, there was Section 375, which focuses on a woman who files a false case of rape. Several critics pointed out that in a post #MeToo India, it seemed like a show of solidarity with Bollywood’s accused men.

And Kabir Singh, panned for glorifying violence and patriarchy, “may end up being the highest grossing film this year”, rues Nanda. “But you also wouldn’t have a mainstream actor like Deepika Padukone playing an acid attack victim [in the upcoming Chhapaak] two decades ago,” she says.

‘Not Beti Bachao, it should be Beton Ko Samjhao’

For many, a flaw of #MeToo is that it stops at social media outrage, when the goal should be changing a mindset and a culture that enable harassment. Aparna Jain, an author and leadership coach who conducts diversity and inclusivity workshops at workplaces, recounts that the men who attended often had no idea their behaviour was unacceptable.

“Women have been conditioned over centuries to not push back, to accept what men do. And men have been taught that everything is theirs for the taking,” she says. “Instead of ‘Beti Bachao (Save your Daughters)’, it should be ‘Beton Ko Samjhao (Counsel Your Sons)’.”

Many men, it appears, did not realise the magnitude of the problem until #MeToo. Delhi-based Prince Aditya and Saahil Kejriwal, both in their 20s, said it was because of the movement that they realised sexual harassment was “so pervasive”.

“So, at one level, a certain sensitisation did take place,” Aditya says. “But as the movement went on, triviality crept in… People started to equate allegations against a Nana Patekar and a Tanmay Bhat, and the public doled out the same punishment. Nuance was lost, which I don’t think is fair.”

At that time, Aditya says, “I started policing myself around women I was interested in. I avoided physical contact, and I developed the practice that ‘cute, romantic moments can wait, one must explicitly ask a girl before kissing her now’.” However, “in the long-term the movement was needed, and for those few innocent men who may have been accused due to personal, malicious reasons, that’s collateral damage I’m willing to accept for the greater good.”

Corporate lawyer Aparna Mittal, founder of Samāna Centre for Gender, Policy and Law, has noticed, over the last year, a significant increase in the seriousness with which corporates implement anti-sexual harassment laws. “For one, companies have started allocating clear budgets for workshops and training sessions. They have institutionalised processes, and they give much more importance to compliance to PoSH and related policies now.”

But Mumbai-based lawyer Rutuja Shinde, who offers pro bono services to survivors, says many women who did speak up ran into hurdles in structural procedures that were meant to help them. “Some ICs were conducting sham proceedings — not conducting hearings or taking any evidence on record.”

A common view is that the movement did nothing for people from smaller towns or financially weaker backgrounds. “It was largely a movement by the privileged, of the privileged, for the privileged,” says a 26-year-old woman who works at a textile export factory in Karur, Tamil Nadu. “Every time I tried to talk about it at work more seriously, it was dismissed as being all about ‘feminism’— which people there associate with trouble-making.”

Chandigarh-based lawyer Sagina Walyat agrees: The movement “amplified the voices of the media and fashion industry, but it did not talk about daily wage workers or domestic workers, because they aren’t on social media. It made an impact somewhere. But for me, it was just noise, especially when I talk about my region.”

Many members from across the LGBTQ spectrum also say the movement only recognised a heteronormative paradigm, and that even after the 377 judgment, social stigma and potential excommunication by family members kept the #MeToo movement inaccessible to them.

Also read: India’s #MeToo accused are back in action – with wedding bells & celebratory cake

Sensitisation not a one-time thing

For Menon, the only way forward is by holding institutions, including the government, accountable. “Men being asked to leave their jobs isn’t going to ensure a cultural change. Corporates need to be willing to pay for workshops, the media needs to help inform people about avenues like the LCCs and NGOs.”

Further, reforming the education system, mobilising more non-profit foundations to help with funding such projects, and perhaps even coming up with a safety ranking for corporates “will add incentives for people to really address the problem”.

Joseph reiterates that sensitisation isn’t a one-time thing. “Like a PUC (Pollution Under Control) card, gender sensitisation should be regular — like renew your ‘GS’ card every year.”

Speaking of her profession, Joseph says, “Every production house raves about how they’ve had no POSH complaints, but their real success should be measured by the number of complaints they get — it means survivors are confident of speaking up and dialogue is happening.”

“Silence is not a measure of how sensitised you are.”