In 1976, there was another upheaval in the lives of workers. Under Sanjay Gandhi’s leadership, the Congress government decided to ‘beautify’ Delhi by clearing jhuggis. The demolition drive was presided over by Jagmohan, who was then vice chairman of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). Residents of the colonies that were demolished by the DDA found themselves hurled to the edges of the city.

Today, the scale of that brutal ‘relocation’ has been forgotten. In fact, hundreds of thousands of workers were forcibly evicted from their dwellings, which were demolished, and the land levelled. I’m not sure if there’s been a mass eviction on this scale anywhere in India or even the world. Underlying Sanjay Gandhi’s violent beautification drive was a brute reality — the value of land — real estate — far outweighed the value of poor workers’ lives. This was decades before the advent of economic reform — the misleading term used for the set of policies of aggressive neoliberalism which normalised such actions.

Take the case of Turkman Gate at the edge of the Walled City of Delhi. Many of the families had stayed in the area since Mughal times. Relocation would have meant a complete uprooting of economic and social ties that went back centuries. On 18 April 1976, the police swooped in, arresting several protestors and, when that was not enough to break the resistance, firing at them. The residents of that colony bravely resisted the bulldozers. There had been no official acknowledgement of how many people were killed in this firing, and the press censorship meant that journalists could not report either. But it is generally believed that at least six were killed, maybe more.

‘Turkman Gate’ became a sort of shorthand to refer to the terrible repression that was unleashed across Delhi on the poor. Industrial workers, domestic workers, street vendors, manual labourers, daily wagers — anybody living in the targeted jhuggi colonies found their dwellings, their meagre belongings, bulldozed. They were given slips that told them where they were to be relocated. A large number were forced to shift east across the river to what was called Yamuna-paar (trans-Yamuna) ‘resettlement colonies’, far away from their places of work.

Also read: The theft nobody talks about—Modern science uses Indian medical knowledge systems without credit

Jagmohan’s career is a telling example of the complete unanimity among India’s bourgeois political parties vis-à-vis attitudes towards the poor. He was handsomely rewarded by three separate — and ideologically mutually-opposed — dispensations for his hatchet job on the poor. During the Emergency, he was part of the inner coterie of Sanjay Gandhi. The Congress rewarded him with the lieutenant governorship of first Goa and then Delhi. He was awarded the Padma Shri as well as the Padma Bhushan. When the Janata Dal-led United Front government replaced the Congress, he became governor of Jammu and Kashmir. He subsequently joined the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 1995, thrice representing that party in parliament and serving as minister in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government.

The Modi government rewarded him for his vociferous support of the abrogation of Article 370, that had conferred special status to Jammu and Kashmir, with the Padma Vibhushan in 2016. Honest officers who work to protect the rights of the poor backed by constitutional and legal frameworks very rarely, if ever, get such rewards. They are more likely to be at the receiving end of punishment postings. I have met many officers in the IAS (Indian Administrative Services) who join the services to be of some help to the poor but often end up disillusioned. In today’s India, it is much worse. The ‘iron framework’ of governance has melted, and officers are suborned to serve the interests of the ruling BJP.

In areas where I worked in north Delhi, too, thousands of houses were razed to rubble. We got desperate messages for help from the workers. The first ‘resettlement colony’ I went to was Nand Nagri in north east Delhi, near Shahdara. If you went to the crowded and bustling colony of Nand Nagri today, it would be hard for you to imagine the sight I saw back in 1976. It was a vast, barren plain with not a tree in sight. The scalding wind of the brutal Delhi summer whipped up dust from which there was no escape. Our faces and clothes, and the meagre belongings of the desolate families, would all be full of dust. Thirsty children howled as desperate mothers hunted for non-existent water sources. It was a nightmare.

At the other end of the city, in north Delhi, was Jahangirpuri, another ‘resettlement colony’. The situation here was like the one in Nand Nagri. Thousands of workers and jhuggi dwellers were simply dumped here. Many of them were poor Muslims who had migrated to Delhi from Bengal. Almost all were daily wage earners who had set up their jhuggis on the banks of the Yamuna, from where they were shifted to Block C of Jahangirpuri. Their condition was absolutely appalling. They had no savings.

Also read: India needs a party like CPI(M). But it finds no takers outside Kolkata colleges now

No one was prepared to give them loans. They were treated in an extremely callous manner by officials. Decades later, in April 2022, poor Muslim residents of Jahangirpuri again faced the wrath of bulldozers, this time under the BJP government and administration, giving no heed even to a Supreme Court order. My Party and I had to physically intervene by standing in front of the bulldozers, waving the court order, which was being violated with complete impunity by the administration. There was a difference, though, a crucial one. In 1976, when the eviction drive started, it was not targeting citizens on the basis of their religion — and secondly, those evicted did get alternative land. Today, the evictions and the bulldozers are almost always targeted at minority community citizens in a blatantly communal manner.

Back in 1976, Delhi’s poor faced the savage brutality and inhumanity of capitalist development as best they could. Almost everybody I met had to take loans at exorbitant rates of interest just to be able to shift to the barren landscape that was to be their new home. They had to hire vans to shift their belongings; they had to build temporary jhuggis to have a roof over their heads; children had to find admission in new schools or drop out of education altogether; women had to find work as domestic labour near the resettlement colonies; men had to commute to their places of work, often twenty or thirty kilometres away. Hundreds of thousands of people, already poor, were pushed deeper into poverty. Factory and mill owners benefited, though, because workers were now totally preoccupied with the cruel fallout of evictions, diverting their attention from the union and the collective struggle.

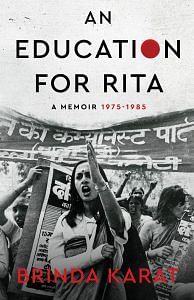

This excerpt from Brinda Karat’s ‘An Education for Rita’ was published with permission from LeftWord Books.

This excerpt from Brinda Karat’s ‘An Education for Rita’ was published with permission from LeftWord Books.