All this was mere colonial-era speculation, but it would later be backed by evidence from geneticists Alan Redd and Mark Stoneking, who found a strong genetic connection between Australia and India. Their study of Indigenous Australian DNA suggested a migration from India to Australia about four thousand years ago, although their results are controversial and other genetic studies have reported different findings.

That genetic evidence may be complemented by features of the archaeological record. The earliest fossils of the dingo in Australia also date back a similar length of time, suggesting that it was an introduced species around the same period. Bulu Imam, from the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, believes the dingo is the direct descendant of the Indian Santal hounds, known as Pariahs, which Indian hunters and gatherers brought to Australia four thousand years ago.

The proposed timing of Indian migration also coincides with the use of more sophisticated tools across Australia. Around that time, flint and chert rock tools began to be used for tasks including hunting, butchering animals, working wood and preparing animal hides.

‘The date that we get for when this gene flow from India occurs – roughly around 4000 years ago – does coincide remarkably well with the first appearance of microliths – the small stone tool technology – in the archaeological record for Australia and with the first appearance of the dingo,’ Dr Stoneking said. ‘It does at least raise the suggestion that all of these events might all be connected.’

Anthropological observers have also perceived Indo–Australian connections in art and culture. The Gond people from the Gondwana region of India paint in a style of dots and dashes and use striking yellow, red, black and white hues in their art, which has been likened to the art of the first Australians. Other parallels in symbols, rituals and language have been identified. These similarities might be caused by a wave of prehistoric migration, or just be reflections of common geographic features and human characteristics. Perhaps they spring from some Jungian collective unconsciousness that throws up universal creative instincts and practices.

Australia’s connections with India were vital to the new British colony after the arrival of the First Fleet. India was Australia’s first trading partner. In the early years, emergency supplies from India saved the colony from calamity when its stores of food dwindled to just a few months’ worth, and its people were ‘nearly naked and [there were] great numbers without bed or blanket to lie upon’. In subsequent decades, more than a third of all ships arriving in New South Wales came from the Indian ports of Bombay, Madras and especially Calcutta. Garole sheep were imported into Australia from Bengal in 1792 and bred their wondrous fecundity gene into Australia’s wool industry. Much of the imported rum, which became a de facto currency in the colony, was Indian spirits made from molasses, cane sugar and palm sugar, shipped from Calcutta. By 1817, two out of every three ships that left Sydney went to India and goods from Bengal nourished the Australian colonies.

In the next century, Australian and Indian soldiers fought together on the battlefield as part of the British Empire. More than fifteen thousand Indians served beside Australians at Gallipoli. Some six-teen hundred of them lost their lives in actions at Gurkha Bluff, Gully Ravine and in the climactic attempt to seize the summit of Sari Bair. In total, more Indians than Australians died fighting for the Empire in World War I.

In World War II, Australian and Indian soldiers were brothers in arms once again, fighting together in defence of freedom in Italy, Singapore and Malaya. Towards the end of the war, in 1944, Australia became the first nation in the world to grant India diplomatic recognition. Emerging into the radically changed post-war world, our two countries had much in common. We were relatively new nations. We shared a region, we shared history and we shared a language, democratic values and even sporting passions.

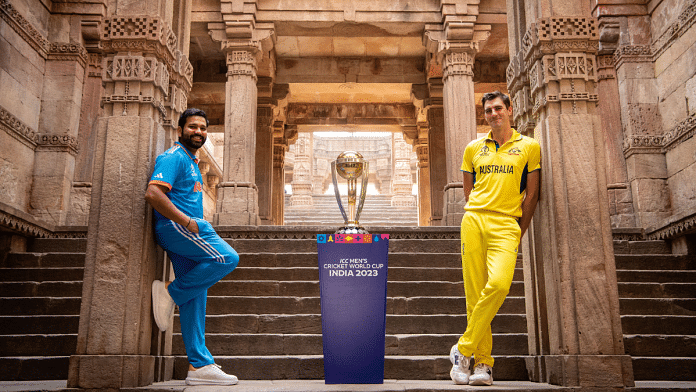

With so many similarities, Australia and India should have been close friends. But behind the well-worn diplomatic platitudes about ‘Commonwealth, cricket and curry’, the truth is that Australia’s relationship with India has been poor for most of the past seventy-five years. For two countries with so much in common, our trade was too low, our investment was practically negligible and our cooperation in defence and global politics produced few achievements of substance.

As India is on the cusp of becoming a global superpower, and Indian Australians head towards becoming Australia’s largest migrant group, the purpose of this book is to analyse Australia’s modern relationship with India in the period since its independence. Australia’s Pivot to India isn’t a hagiography of the bilateral relationship, and it isn’t a starry-eyed attempt at painting a rosy picture of the future.

This excerpt from Andrew Charlton’s ‘Australia’s Pivot to India’ has been published with permission from PanMacmillan.

This excerpt from Andrew Charlton’s ‘Australia’s Pivot to India’ has been published with permission from PanMacmillan.