For many years since, I have been baffled by two apparently conflicting sides to Advani. In music, cinema, and books, his taste is remarkably refined. An admirer of Satyajit Ray’s movies, he is fond of watching art films. His campaign kit for the 1989 elections included Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock. I got to know Advani better while travelling with him to different parts of the country. Flying to Aurangabad on the home ministry’s special plane, he showed me a book a Brazilian writer had signed for him. ‘He has signed his other books for me also,’ he said, with a tinge of pride in his voice. Soon after my book An Escape into Silence was published, a left MP I met in the Parliament library said, ‘The home minister of India was seen reading your book.’

I was one of the journalists most critical of his use of religion in politics. But that never strained our personal relations. The day after the Vajpayee government was sworn in, the Times of India editor, Dileep Padgaonkar, walked into the political bureau in the evening. ‘Ask Advani what he has to say about Rushdie,’ he told me. A man of fine literary sensibilities, Paddy, when he was not around, preferred such stories. I called Deepak Chopra, Advani’s man Friday.

‘He’s in a meeting,’ Deepak said. After half an hour, he connected me to his boss. ‘Salman Rushdie is welcome home,’ Advani said. Asked about the Rushdie books he had read, Advani mentioned Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses. That was on the paper’s front page the next morning.

It was a favourite media game to pit Vajpayee and Advani against each other. I too did that to some extent. However, I made an effort to study their comparative strengths and weaknesses as well. Advani was essentially a strategist whose decision making would be based on hard analysis of past events. Vajpayee, on the other hand, was spontaneous in his political reflexes, a man with a fabulous common touch. His politics was rooted in his culture, which was plural and therefore expansive. Though raised on a heavy diet of Hindu nationalism, he seemed to have somehow accepted the essential centrism of Indian politics and tried to make adjustments to the country’s plural environs.

Advani too was guided by a syncretic tradition, but that was supplanted by his personal experience. As a student at St Patrick’s High School, Karachi, he was impressed by the liberal Catholic values. Though an RSS activist even as a teenager, the milieu he grew up in was multicultural. The pre-Partition Karachi he fondly remembers had a sizable Parsi community, also Christians, Jews and a small number of Anglo-Indians, apart from Hindus and Muslims. Hardline Hindutva would be alien to someone from such a background. But the trauma of Partition—the flight he took on 12 September 1947 all alone to Delhi, the recent bomb blast in Karachi attributed to the RSS and subsequent arrests, the uprooting from what he had so far known as home to cross over to India as a refugee—all this must have left scars on the impressionable young man.24

In fact, Advani gained prominence in Jan Sangh politics because of his good command of English. He was, perhaps, the only senior party leader in those days who could expertly handle the English media and represent his party on forums outside their Hindu nationalist milieu. His doctrine of Hindu domination was hewn by displacement, massacres, and the extremities of Partition. A born-again Hindu, he wanted to see India as the land of his people, dispensing with the effete constitutional niceties of a secular democracy. Despite his strident political position, memories of St Patrick’s must have lingered on, as did his love for books, cricket and good movies. As home minister, when his movement got restricted, he would go to the small government auditorium near Gole Dak Khana to see movies specially screened for him. He almost broke down while watching Aamir Khan’s Taare Zameen Par, a deeply moving film about the suffering and final triumph of a dyslexic child.

A year after I left mainstream journalism, I met Advani at a book launch at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. After the programme, we talked over tea. I told him I had moved into publishing.

‘Do come over, it will be nice knowing about your work.’ ‘I would love to come with a couple of our books.’

‘Books are always welcome.’

He was still in the same Prithviraj Road bungalow, which used to be one of political Delhi’s most prominent addresses during his years as deputy prime minister. Now it was a ghost house, with hardly a visitor around. In the parking space outside, mine was the only car. The security paraphernalia had remained intact, but there was barely any activity. When I was ushered into the bungalow, there was just another visitor who had come from somewhere in Maharashtra. ‘Aap Dada se milne aye hai?’ he asked me, perhaps comforted that there was another man who had not forgotten Advani.

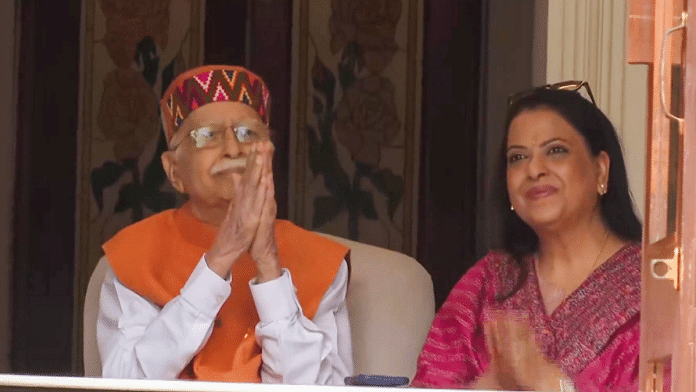

Advani sat there as always—erect, agile, remarkably fit for someone above ninety. The sculpture in one corner of his office represented his idea of India—tough, muscular, strong. We talked for a long time about the changing face of the media. He recalled some of his journalist colleagues from the days he had worked for the Organiser. At one point, he let personal memories wash over him. ‘We got married in Mumbai. A pracharak, I had decided to go for the ceremonies in my usual dhoti-kurta. Sensing that, Kamla had sent word that she would not marry a man in dhoti-kurta.’ He laughed.

‘So, what dress did you finally choose?’ I asked. ‘I went in a suit.’ Nostalgia had set in.

This excerpt has been taken from Bhaskar Roy’s ‘Fifty Year Road’ with permission from Jaico Publishing House.

This excerpt has been taken from Bhaskar Roy’s ‘Fifty Year Road’ with permission from Jaico Publishing House.