In a subtle move, the prime minister was involving Finance Minister Manmohan Singh in the Kashmir affairs discussions. Perhaps this was intended to put before the people of Jammu and Kashmir a credible, non-political face as and when required. The sidelining of the Union home ministry did create some ripples and led to the exit of an upright and able home secretary, Madhav Godbole, who was also the secretary of the new Kashmir Affairs department. Rajesh Pilot was in some ways responsible for the exits of Godbole and Governor Gary Saxena. Gary Saxena was replaced by General Krishna Rao. Such reorganisation sent a much-needed strong signal all around that there was a fresh political approach to the problem.

The brick-by-brick approach largely went unnoticed by the media. In Jammu and Kashmir, the media was under attack by militants who wanted their cause and activities to get visibility. On the other hand, the state government had introduced a ban on local media for giving space to separatist voices. Facing this crossfire, many state newspapers chose to shut down. Newspapers from outside were airlifted but they could not be distributed widely. It took some effort by central government officials including me to convince the state government not to pounce on local newspapers when they published news and views favourable to the militants, so long as they also published news and views of the other side too. A special effort was launched to offer official advertising support to the Jammu and Kashmir newspapers that dared to publish. I was asked to undertake visits to Jammu and Kashmir to revive the state’s media. Many of the state newspapers were in dire straits. When they found it difficult to gain access to newsprint, arrangements were made to make it available. The state information department was ill-equipped to serve the state media. As a result, the governor would often call for my assistance in dealing with the media in Delhi.

At the time, there was a ban on foreign media visiting the valley. This deprived them from gaining first-hand knowledge of the situation on the ground. Many foreign outlets had appointed local stringers who worked below the radar and reported only sensational news. As there was no free flow of information and the government news outlets had lost credibility, the people of the valley mostly relied on BBC Radio, whose signals reached the remotest corners. The I&B ministry made its own efforts to install powerful TV and radio transmitters and revamp the programmes in Kashmiri language. The prime minister ensured that the ban on foreign media was lifted. No doubt there was an initial flood of stories adverse to the government, but this changed as the ground situation in the valley improved.

The union home ministry had, in a wooden-headed way, decided not to allow diplomats stationed in India to visit Jammu and Kashmir. There was apprehension that diplomats of some countries were in touch with the state’s separatist leaders. Sometime in 1994, the prime minister had this decision reversed. His reasoning was that the ground situation in the valley had changed, and diplomats should be facilitated to assess the situation for themselves and report back to their governments. This deft diplomatic measure changed the perception of foreign governments who had fallen prey to Pakistan’s propaganda. Once diplomats from the US undertook a visit to Jammu and Kashmir and returned convinced that the people of the valley were fed up with militancy and were ready to elect their own state government, there was a remarkable change in the news reporting about the valley, especially by the US media. This set the tone for other media outlets to see and report the change in the situation on the ground.

In the mid-1990s, during a conference in Delhi on reforms in the criminal justice system, Rao brought up the allegations of human rights abuse by the security forces and the necessity for India to deal with human rights issues in the broader context of democracy and the Constitution. He then swiftly moved to set up an independent Indian human rights commission. Once the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) began functioning, the separatists could no longer shoot from Amnesty International’s shoulder. Slowly, the NHRC managed to persuade the security forces to sensitise their personnel about the need to respect human rights while dealing with a civil conflict.

Another of Rao’s masterstrokes was the way he dealt with Pakistani attempts to use the UN to condemn India on its human rights record. Islamabad managed to bring up a resolution on the subject. Rao adroitly sent a powerful delegation under the opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee to argue India’s case opposing this resolution. The Vajpayee-led delegation succeeded in persuading the UN body not to take up the Pakistan resolution.

Despite continued provocations from Pakistan, Rao did not shun opportunities like international conferences where he could meet and hold talks with the prime minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif. In fact, he made serious attempts to resolve various issues between the two countries even while disagreements about terror in Jammu and Kashmir and its status continued. During more than one such meeting that took place between 1991 and 1993, India presented ‘non-papers’ (a diplomatic term meaning ‘not formal’ and not on record) to Pakistan on other bilateral issues for discussion and settlement.

One of the irritants between the valley’s separatist leaders and the union government was in regard to the former contacting Pakistan’s diplomats in India and political leaders in Islamabad. India’s foreign and home ministries had taken a hard-line position and frowned upon any such contacts. Almost every year around India’s and Pakistan’s Independence Days, there was a recurring echo of this irritant when Pakistan’s embassy in Delhi invited the valley’s separatist leaders to the Independence Day reception it hosted. When this matter was brought up to Rao, he reportedly showed no hostility to valley leaders meeting Pakistani representatives in India; his typical reaction was, ‘Let them. So what?’ Such level-headedness helped to cool things and expanded dialogues and trialogues.

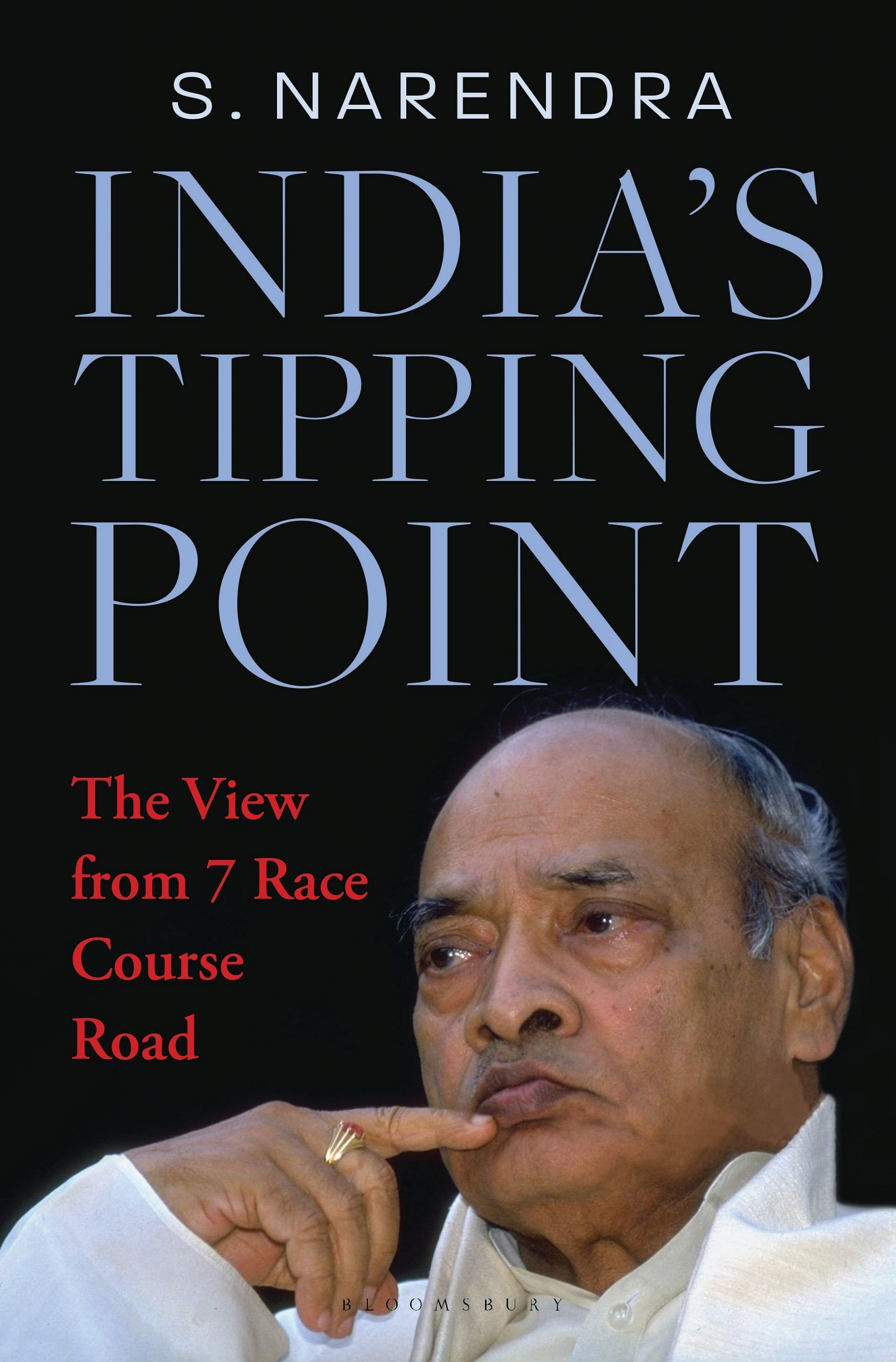

This excerpt from S. Narendra’s ‘India’s Tipping Point’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury Publications.

This excerpt from S. Narendra’s ‘India’s Tipping Point’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury Publications.