Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s Europe’s India: Words, People, Empires 1500-1800 is a rich experience for its detailed source of information and analysis.

Browsing Europe’s India is much like strolling past a finely curated museum collection of canvases. Through the diverse agendas, travails, and adventures of Europeans both famous and less significant, the broad sweep of the centuries comes alive in all its complexity — a rich experience for the lay reader and a detailed source of information and analysis for contemporary historians.

Formidable erudition and a liberal approach to historical perspectives make Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s Europe’s India: Words, People, Empires 1500-1800 a valuable addition to the history lover’s bookshelf.

Straddling three centuries, the book explores how Europeans of varied stripes, from the first Portuguese sailors who sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in the late 15th century, to the English, Dutch, French, Italians, and Germans, perceived the subcontinent. The manuscripts, letters, artefacts, and paintings from India that these travellers – from seafarers, ambassadors, soldiers, and missionaries to artists, scholars, and adventurers – collected and took back with them, besides their personal observations and officially recorded chronicles, contributed to shaping Europe’s concepts of the subcontinent’s history, politics, religions, and social structures.

A central premise of the book is Subrahmanyam’s rejection of the competing notions of two Indias––the ‘real’ India versus the exoticised (and in recent times, much criticized) version beloved of Orientalists. Knowledge, says the historian, is imbibed according to the circumstances in which it is produced. In his words:

“…it appears to me perfectly legitimate to ask how the concrete and institutional conditions within which certain forms of knowledge were produced affected both the form and the content of the knowledge itself, rather than assuming –– in some falsely naive manner — that knowledge is by its very nature neutral and innocent, and just one of those things of which “more is better than less.”…”

Europe’s India portrays not only the multiple influences through which Europe viewed India but to how a subcontinental thought in turn shaped Europe in terms of culture, religion, and trade.

The Introduction sets the tone of what’s in store with a series of marvellously curated vignettes. Their purpose — to bring home the not-so-obvious truth that there existed among Europeans, even those from a single nation, a broad range of perspectives on India. The famed French traveller, philosopher, doctor, and astronomer Francois Bernier’s quote opens the Introduction with this gem:

“For the rest, beware of Mughal women…Almost all the Dutch and the English have their own [women], but even so they are often nicely trapped, and not only do they lose their souls, but also their goods and bodies. And this even more so if they begin to drink this bowl-of-punch [ce bouleponge] in quantity, as well as arrack; whereupon they become incontinent and rotten with the mal de l’Inde, and at any rate they shake all over…”

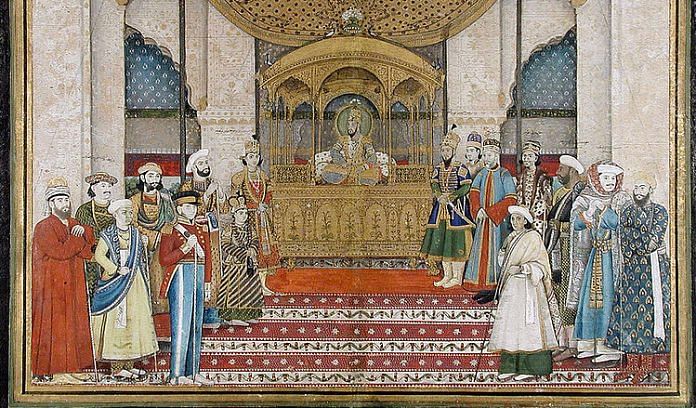

A survival guide to India, no less! Juxtaposed against this are French jeweller Augustin Herryard’s descriptions of his time at the court of Mughal Emperor Jehangir:

“I have been in this country neigh years. All the Frenchmen I had brought with me died in the first year and thereafter I took service with this King, the Great Mougoul.

I made a royal throne in which there are several millions of gold and silver and several other inventions such as cutting a diamond of 100 carats in ten days. It is impossible to believe in the magnificence of this King and I shall mention only three aspects of them’ his large diamonds; his large balas [rose-tinted] rubies of which he alone has more than all the men in the world; and when he marches through his kingdom, he takes with him fifteen hundred thousand human beings, horsemen, soldiers, officers, women, and children, with six thousand elephants and much artillery which serves no purpose but to show his magnificence..”

The first two chapters, set in the sixteenth century concern Portuguese observations of India through the divergent perspectives of official chroniclers and the more informal, personalized accounts of Christian missionaries. The second chapter examines 17th and 18th century texts that sought to understand the ‘Gentile religion’, Hinduism. A key focal point is the Portuguese interest in India’s caste system and its origins.

Sixteenth century Europe’s understanding of India was also influenced by the many collectibles brought back from the subcontinent. In Chapter 3, we encounter the relatively less known James Fraser, a Scotsman who lived and worked for several years in western India. During his longish stints in India during the early 1700s, Fraser accumulated a sizeable collection of written material — Persian manuscripts, letters written by nobles of the Mughal court, and royal portraits now housed in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University — that throw light on the political milieu of the times. The value of Fraser’s writings and his collections, says Subrahmanyam, lies in his appreciation of the worth and ‘scholarly integrity’ of western Indian thought, despite his unfamiliarity with these traditions, although it must be borne in mind that “such attitudes were also related to a particular political context, when Europeans still did not try to dominate the subcontinent.”

In the final chapter, Subrahmanyam walks us through the mid- 1700s and up to the early 19th century with a motley group of Europeans, “A French entrepreneur and military commander, a Portuguese ecclesiastic…, a Franco-Swiss adventurer who was also an avid collector of things South Asian, and finally a Scotsman who eventually participated as an East India Company administrator in South India and Gujarat.”

There are fascinating nuggets along the way such as the Frenchman Antoine Polier’s determined efforts to learn Sanskrit and take home with him what may have been the first translated version of the Vedas and the Scotsman Walker’s obsession with the cruelties heaped upon ‘Hindoos’ by Tipu Sultan.

Poornima Narayanan is a Delhi-based freelance writer and editor.