Gujarat is a model state, if one were to take Prime Minister Narendra Modi at his word. In the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha election, the ‘Gujarat model’ was cited as the template for India.

Evaluating models of growth is difficult. A simpler and manageable question is: How does the state perform in terms of sending children to school and retaining them there? After all, educating children is the biggest long-term growth hack for any society. A more educated population invariably ends up being more prosperous. Educated people hold jobs better, incentivising businesses to set up shop in their society. They can innovate better and move to higher-value work. All of these factors contribute to the gross state domestic product (GSDP). Education is good on its own; but even if people want to put a material angle to it, it still is a necessary metric of future growth.

The data on Gujarat tells a different story than what PM Modi’s claims suggest. The state is performing worse than not just Maharashtra, its equally prosperous neighbour to the south, but also Rajasthan — the far poorer neighbour to the north. And shockingly, only about as well as Madhya Pradesh, another very poor neighbour to the east.

Difficulty of comparing states

Comparing states in any one area of governance is often difficult and counterproductive. States have different starting points. So, comparing one absolute metric at any given point tells us very little. What we want, if we are to measure states in one area of governance, is an ability to measure how well a given state has done relative to its own base and benchmark, and then compare that growth with that of other states with similar bases.

Another problem is that policies have long gestation periods; they come to fruition without regard to election cycles. This makes the measurement of the success or failure of any one government difficult. It’s very likely that one government, under its tenure, is seeing the effects of policy implemented by a previous government. So, one needs to be careful in attributing success or failure to governments, and therefore, political parties.

Economic policymaking, even more notoriously, is dependent on factors beyond the span of control of state governments. They depend on the investment climate, which, in turn, is decided by global business cycles. Worse, they are bound by trade policies that the Union government controls. A state government can, at best, offer good governance in all other areas and hope that it translates into economic activity.

Also read: Does BJP’s double-engine sarkar achieve its basic claim of better growth? Data says no

A better metric

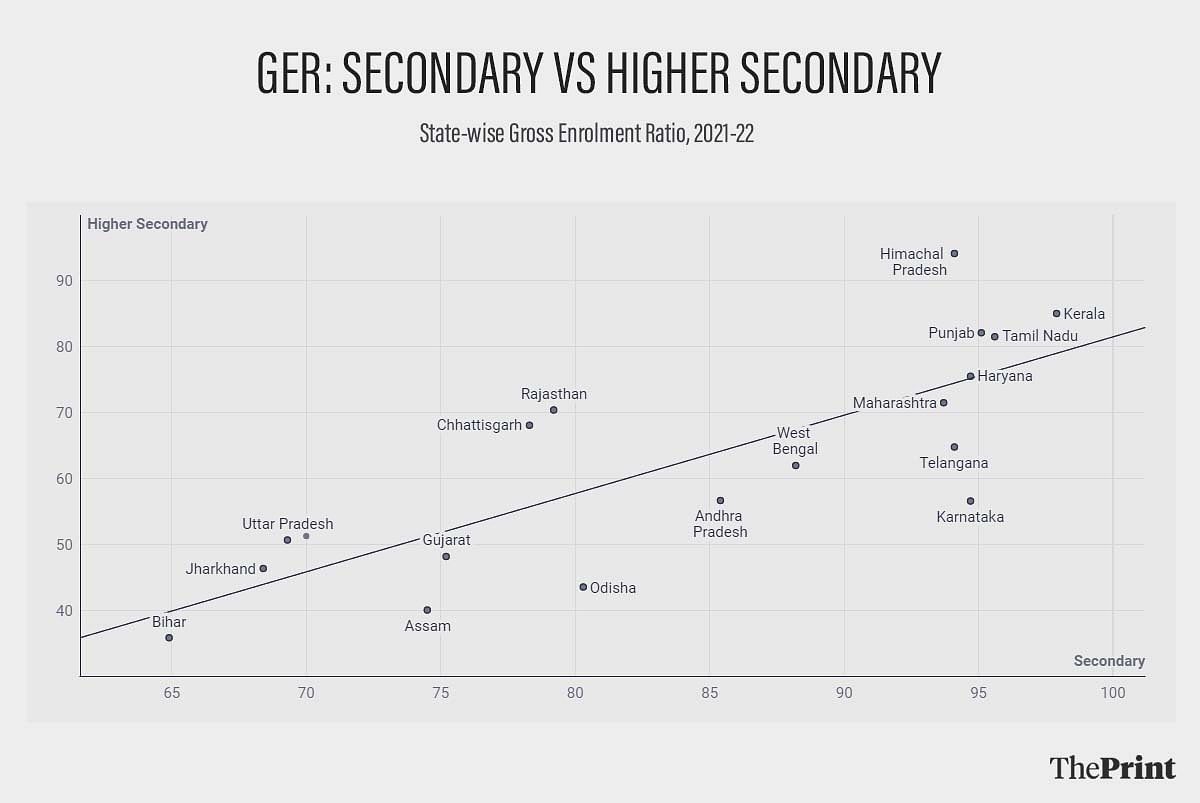

In this regard, education offers a relatively easy data set to work with. Children who went to secondary school, ideally, should continue with higher secondary education. That retention is good governance in general. The secondary school level’s gross enrollment ratio (GER), thus, forms a base, which is the result of long-term policy and the relative levels of a state’s overall development. Conveniently for us, graduation from secondary to higher secondary school happens within two years. So, it happens within the tenure of an elected government and does not run into long gestation periods.

One would, therefore, expect relatively prosperous states to cluster together for their base. And maybe vary in terms of their retention rate. Similarly, one would expect poor and underdeveloped states to cluster at the lower end of the base.

The chart above is somewhat predictable for some states while entirely shocking for others. States like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana, Punjab, Haryana, Maharashtra, and Himachal Pradesh have indeed clustered together in terms of their base while showing significant deviations in their relative retention. While Himachal Pradesh has done the best — by having the highest positive residual — in retaining children in higher secondary school, states like Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Kerala have also done better than the rest of the country relative to their current status. They have a positive residual despite having a high base. Maharashtra and Haryana are near the trend line and are doing about as well as one would expect them to. Telangana and Karnataka, though, are doing significantly worse than their peer states. Their high bases offer them a cushion, but they should be worried.

States that are poor and generally backward, such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand have predictably clustered at the opposite end. Bihar seems to be doing worse in retaining children in higher secondary school, even relative to its already terrible status. While Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh are doing better than their relative base would suggest, it will take them a while to catch up with developed states in terms of absolute GER.

Also read: India’s wicked resource allocation problem has an answer— break UP into smaller states

Surprises and a tragic tale

The real surprises among states are Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh. These are poor states that have had poor development metrics for a long time. They both belonged to the infamous acronym BIMARU, a group of poor and backward states (Chhattisgarh was carved out of Madhya Pradesh in 2000). But Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, as their position in the chart shows, have broken out of their BIMARU peer group. Not only do they have a better base compared to their BIMARU peers, but their current performance in keeping children in school is also very good as their large positive residual shows.

On the contrary, Gujarat is a tragic tale. For a state that’s one of the richest in India, it’s lagging far behind Rajasthan both in terms of its base and its more recent efforts.

How has Rajasthan zoomed past Gujarat? More importantly, why is Gujarat closer to the BIMARU club rather than its economic peers like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu? The budgets of Rajasthan and Gujarat offer one clue. For the past 10 years, Gujarat has consistently had a lower than national average allocation for education as a ratio to its overall expenditure. Rajasthan has had a significantly higher allocation compared to the national average.

Of course, having a higher allocation for education is not a sufficient condition for achieving a higher gross enrolment ratio in higher secondary education. It is, at best, a necessary condition. Children have to be reasonably healthy in the first place to show up at school. They must feel safe, and their parents have to perceive value in sending them to school. Parents feel that way only if the society is relatively equal, and all educated kids have a shot at prosperity, not just the rich ones. All these aspects of basic governance are reflected in the GER.

That a wealthy state like Gujarat has a large segment of its people who do not feel the effect of basic governance is shocking. But the fact that Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh punch well above their weight is a lesson for poor states: There is light at the end of the tunnel, and effort bears fruit.

This is also a lesson for the Union government: states are complex and complicated. What the top-performing states need is vastly different and often orthogonal to what the bottom-performing states require. For example, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Punjab can now focus on output metrics. They don’t need to build more schools or incentivise students to attend school. Whereas Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and Bihar face a significant hurdle in getting kids to stay in school, which warrants entirely different policy choices. These states would do well to learn from Rajasthan’s success story and emulate it.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

👍