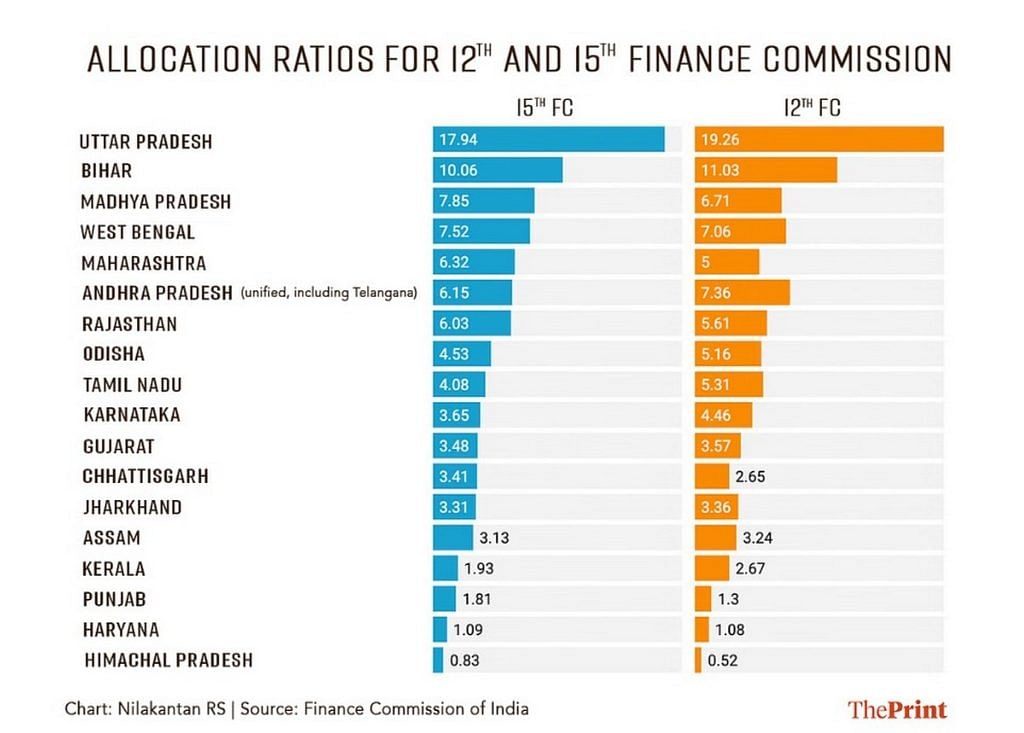

One of India’s most pressing problems is that its federal structure is facing increasing strain, with the southern states complaining for a while now about unfair treatment in resource allocation. The allocation ratio— the proportion of tax revenues devolved back to each state from the Union has steadily dropped for these states in the last 30 years. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka have all lost their allocation significantly from the 12th Finance Commission onwards.

The complaints have only become louder with the 14th and 15th Finance Commissions adopting 2011 Census data as the basis for population, as opposed to 1971 Census data as was the case previously. States in the Indo-Gangetic plains have had a much higher rate of population growth owing to higher fertility rates, while southern India had stabilised its population in line with policy demands. This makes their grumbling even more legitimate, given the negative correlation between falling fertility rates and female literacy.

The issue that states like Rajasthan, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh face is genuine as well. They are generally much poorer and more developmentally backward than their southern counterparts. Naturally, they need greater assistance. After all, we need to build more schools and hospitals in parts that lag behind in health and education, not less.

People in southern India, except those with extreme views, aren’t going to complain about some of their money being routed to these states for improving their basic health and education. They may have a philosophical issue if that money is spent in ways they don’t approve of, especially when they don’t even have a say in how their tax money is spent. But these are secondary concerns. The main grievance of most southern states is the quantum of funds.

The most glaring problem in the federal structure and its resource allocation problems becomes apparent when one looks at the data — it is that Uttar Pradesh is too big and corners resources by virtue of its size, which seems unfair to other states.

Also Read: States with English-medium schools have higher wages. Look at Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab

UP’s monopoly of resources

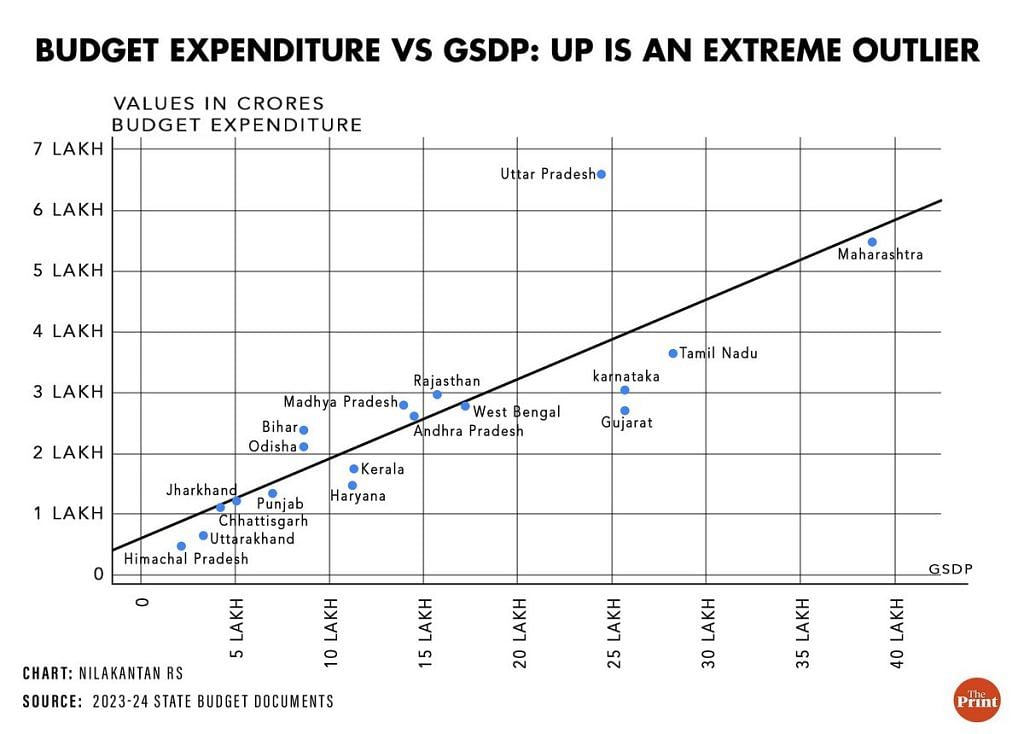

Uttar Pradesh’s disproportionate allocation of resources can be seen in a simple chart comparing the Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of each state with its actual budget expense. Uttar Pradesh is an extreme outlier.

Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Bihar are similar to Uttar Pradesh in most metrics. Their budgets, however, only slightly exceed those of other states compared to what their GSDP would permit. This is explained by the slight positive residual for these states in the chart above.

Essentially, these states— represented by dots above the regression line— draw funds from states below the line. The wealthier states draw less from the Union for their own budgets than what they contribute. This seems fair in the spirit of helping those in need of help.

Uttar Pradesh is nothing like its peers, though. It enjoys a budget that far exceeds its economic size.

Even after considering Uttar Pradesh’s population — which is significantly larger than Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh — the degree to which it is an outlier is anomalous.

Uttar Pradesh’s population is roughly twice that of Bihar. A reasonable expectation, therefore, would be to have its positive residual—the perpendicular distance of the state from the regression line—to be twice that of Bihar.

However, a quick look at the chart tells us Uttar Pradesh’s positive residual is much larger. Additionally, Uttar Pradesh is economically better off than Bihar, which means that its positive residual, if anything, should be less than twice that of Bihar.

What’s the reason for the anomaly?

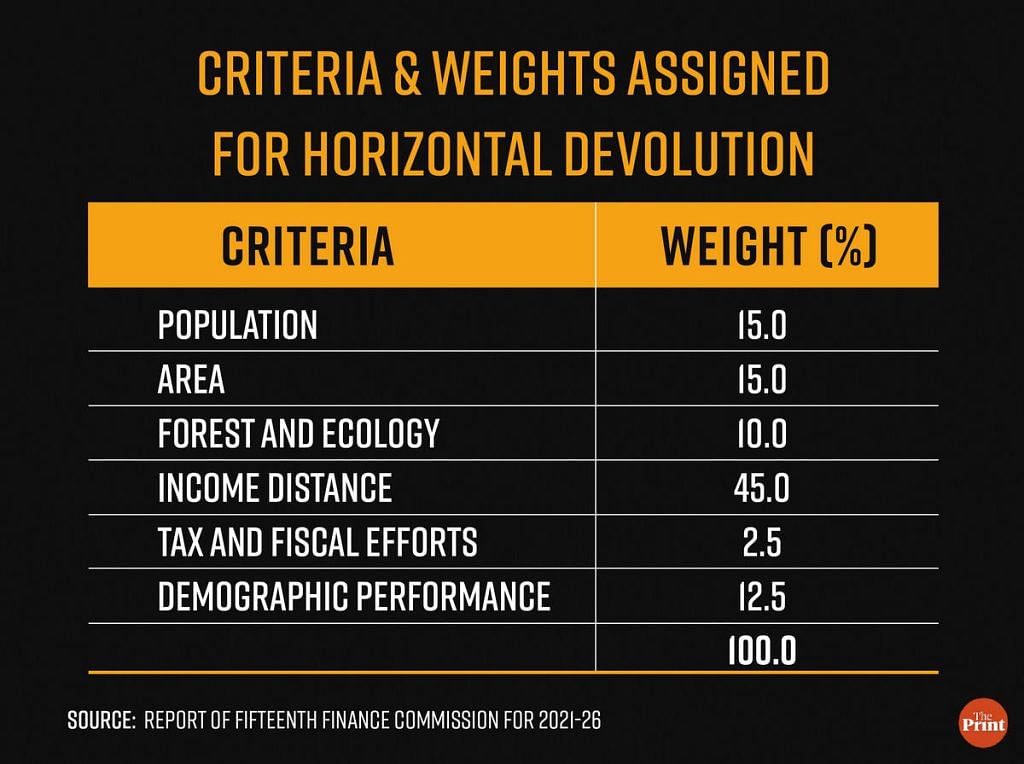

To understand why this anomaly happens, let us look at how the allocation ratio is calculated. The factors and their weights that contribute to deriving the allocation ratio in the 15th Finance Commission are given in the table below.

A cursory look at the factors would make them seem fair. But a closer examination of how the eventual allocation ratio is arrived at explains why population has a non-linear effect. The factors above are calculated for each state and then scaled again by that state’s population to arrive at the final allocation share.

For example, consider income distance. It is the biggest criterion for deciding the overall allocation ratio in the 15th Finance Commission’s report. One may agree or disagree on the merit of having 45 per cent of the total weightage assigned to income distance. But what’s strange is that though the criterion is income distance, it ends up as a proxy for population in the way in which it has been calculated.

The income distance of a state is determined by comparing its average per capita GSDP, taken over three years, to that of Haryana (which is used as a benchmark by the Finance Commission for its relatively high per capita GSDP).

So far, it seems reasonable. Except, then, this distance is scaled by the 2011 population of each state! The end result renders income distance as a metric that is heavily correlated to the population of 2011.

In other words, since multiple factors are scaled by population, its impact on the end ratio becomes almost exponential. This means that the state with the highest population ends up getting an outsized share in resource allocation, irrespective of other metrics.

A useful way to understand this problem is to look at the allocation ratios of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand — states carved out of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh respectively.

In the cases of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, their economic output and other development metrics are either at par or worse than the states they originated from. This suggests that they should have higher or at least comparable positive residuals compared to their parent states. Except, the opposite is true.

Large states corner resources even when compared to other states with similar development metrics. It is perplexing that the Indian Union deems Uttar Pradesh in need of almost three times the additional assistance— in relative terms— of Bihar even though it is better off in economic terms.

Another state that benefits significantly from this exponential effect of population on allocation ratios is Maharashtra. As the second-largest state in population terms, Maharashtra has avoided the fate of other industrialised and advanced states like Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, which have experienced a significant reduction in their share of devolution, resulting in large negative residuals. Maharashtra, being the second-largest state, ended up with a relatively small negative residual.

Also Read: ‘India a superpower or not’ debate can wait, first answer this—how many new mothers live here?

Population cap could solve the problem

An obvious truth emerges from the data — the current formula, which uses population as a scaling factor for variables that are unrelated to population, gives an unfair advantage to states with more than 10 crore people.

This comes at the expense of both prosperous and poor states. Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have been crying foul over resource allocation, but states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh should be raising an alarm too.

The solution is also pretty obvious — imposing a cap on the population size of states. A simple rule could be that no state can have a population greater than 10 crore. Carving smaller states out of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, for example, will solve India’s wicked resource allocation problem to a large extent. This way, Uttar Pradesh, or the new states it spawns, would stop monopolising resources. Maharashtra, or the prosperous little states it begets, would have to contribute more to other states.

The new smaller states will naturally move closer to the regression line in the chart above.

This will work in both directions. Some of the resources that Uttar Pradesh has been cornering will be sent to states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. And states that currently contribute a lot of their resources will give up a little less, as Maharashtra will share their burden a bit more.

Overall, the cap will mean that the population factor won’t zing states so badly either way.

The answer to Karnataka’s questions on resource allocation rests on Uttar Pradesh not being bigger than most countries.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)