Southern states raise issues about resource allocation problems. They do this often. They do this loudly. And they do it persistently. Finance ministers of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh have all pointed out the unfairness of the Finance Commission’s allocation to their respective states and southern states in general. They often argue that by virtue of being relatively prosperous and well-administered, they stand to lose. They make the case that the Union government uses a perverse system to incentivise bad governance.

The politics of the South, in effect, is also driven by this antagonism with the Union government in some ways. It has been a mainstay in the politics of Kerala and Tamil Nadu for a long time. Ironically, in Karnataka where the election was contested between two national parties, the issue featured prominently. Telangana’s incumbent chief minister had, in fact, proposed a national alliance based on these issues.

A question that ordinary people, political partisans and thoughtful people alike ask at this point is: what about Maharashtra?

It is a good question. Maharashtra is one of the richest states in India. It’s well administered. It has good social development metrics. It’s not in the Indo-Gangetic plains. So one set of partisans asks the above question assuming that if Maharashtra isn’t complaining, other states have no reason either. If those states still do, their reasoning goes, it must be because of petty politics. Another set of people ask it with genuine befuddlement: how is it that data suggests these resource allocation problems yield worse outcomes for southern states despite them being similar to Maharashtra in many ways?

Also read: Something ties UP to TN: their inability to spend allocated budget. And parties thrive on it

Breaking down allocation ratios

A simple place to begin is to look at the allocation ratios. The allocation ratio and how that metric has moved over a two-decade period is probably a good predictor of how a state’s politics has evolved in that time. It is the ratio in which central funds are transferred to each state, as decided by the Finance Commission. Therefore, it is the biggest driver of how well a state can be run relative to its own levels of prosperity. State governments and political parties may posture and say things that may or may not be true, but the truth of monies in their treasury is a truth whose physics they cannot escape. And as states get more and more prosperous, their citizens demand better and better services. That is a political reality leaders with hopes of getting re-elected must contend with.

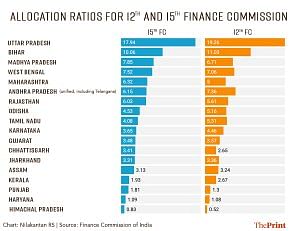

The change in allocation ratios from the 12th to the 15th Finance Commission, which covers the last two decades, shows that the southern states have all lost allocation significantly in relative terms. Thus, it makes sense for them and their politics to be agitational on this subject. Maharashtra, interestingly, has gained in allocation ratio in this period. In the 12th Finance Commission, the state had an allocation ratio of 5 per cent. In the current period, as dedicated by the 15th Finance Commission, it has an allocation ratio of 6.32 per cent. For comparison, Tamil Nadu, similar in terms of prosperity and development, went from 5.31 per cent to 4.08 per cent in the same period. It’s no wonder, therefore, that Maharashtra isn’t at the front of this line crying hoarse. Whereas Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka are.

Also read: West Bengal economy’s fall has been stunning. Too obsessed with agriculture

A skewed formula

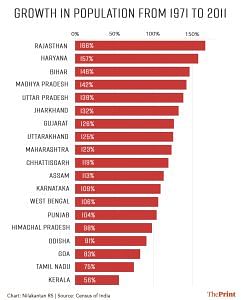

The question then becomes: why does this happen? The answer, as with every other question in India, rests in the data of demographic divergence. The allocation ratios are determined through a formula that uses population as its dominant factor. And in the 12th Finance Commission, 1971 Census data was used for population. In the 15th Finance Commission, 2011 Census data was used.

In the period between 1971 and 2011, the population of Maharashtra grew by 123 per cent. That puts the state in the middle when we rank states on population growth for the 40-year period. Rajasthan had the highest growth, with most states in the Indo-Gangetic plains for company. Kerala, with 56 per cent, and Tamil Nadu, with 75 per cent, had the lowest population growth among large states during that time.

The allocation ratio formula that the Finance Commission devised is extremely skewed. Nearly 75 per cent of the weightage, in the ultimate analysis, goes toward population. Given that, and given the use of the 2011 Census, where Maharashtra’s population grew by 123 per cent in the preceding 40 years, it is but natural that the state isn’t badly affected. It’s also obvious, therefore, that Kerala and Tamil Nadu are. Which also explains the political noise in the South and the absence thereof in Maharashtra.

One important aspect to note in all this is: it’s not as if Maharashtra is gaining money that isn’t commensurate with its size and economy. In fact, it’s now been merely restored to parity. The Indian Union was quite unfair to Maharashtra in the 12th Finance Commission as it got a lower allocation ratio then, compared to even Tamil Nadu, a much smaller state. But that return to parity likely makes resource allocation less of a political issue in Maharashtra, which is why politicians from that state aren’t vociferous about it like their southern peers.

So, the next time your friend from Mumbai asks “What about Maharashtra?” tell them that age-old adage: demography is destiny. But hopefully, you don’t sound like the fascist who most used that statement.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)