State governments are terrible at providing budget estimates. The variance between budget estimates or the allocated amount and actual expenditure, which we often get only two years later, is so vast that the original estimate often makes no sense. It might as well have been a random number.

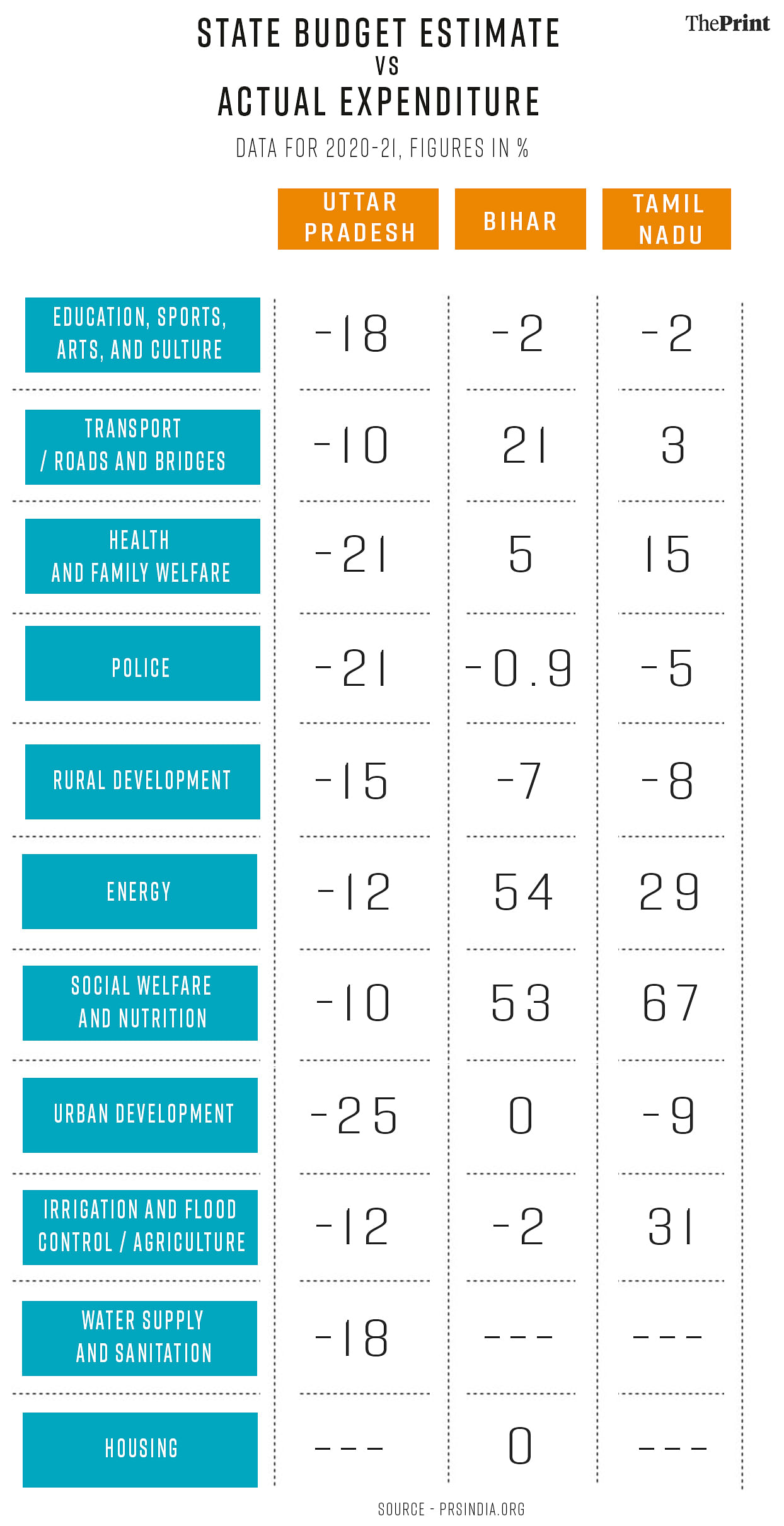

One can understand estimates of tax collection being volatile. That depends on economic activity, which is difficult to predict. But what is worth noting is that estimates of expenditure in core areas of large states vary vastly. The budget estimate for water and sanitation in Uttar Pradesh, for example, is 18 per cent higher than the actual expenditure in 2020-21. Similarly, the estimate for transportation — which includes roads and bridges — was 10 per cent higher than what the state actually spent. If the state isn’t able to spend the allocated money in a given sector and misses by such wide margins, it simply points to a lack of state capacity.

This problem is not unique to Uttar Pradesh. Bihar’s actual expenditure in agriculture, for example, is 2 per cent lower than the budget estimate for 2020-21. Most states in the Indo-Gangetic plains have a similar issue.

In the important areas of health and education, Uttar Pradesh missed the expenditure estimate in 2020-21 by 21 per cent and 18 per cent. Tamil Nadu, a relatively well-administered state, in contrast, overshot the health budget by 15 per cent while it fell short of the education budget by almost 1.8 per cent for the same year. Similarly, in social welfare, Uttar Pradesh missed the budget estimate by 10 per cent while Tamil Nadu overshot it by 67 per cent.

Fiscal deficit and state capacity

An interesting trend that the data reveals is that states with a lower variance between their estimates and their actual expenditure do better in terms of governance outcomes. That is, states with better capacity to spend the allocated money are better governed. In one sense, that’s tautological. In another, it points to a flaw in the most basic aspects of governance that no amount of additional funding for specific areas will solve.

If a society is under-educated and malnourished, for instance, additional funding for programmes in those areas won’t solve the problem if the government has no capacity to spend these funds.

Fiscal deficit is commonly used as a measure of a state government’s performance by the media and the Union government — the lower the better.

But what the fiscal deficit data shows is that states with better capacity to spend end up with a higher fiscal deficit than those that don’t. As a consequence, states with higher fiscal deficit and higher tax bases often have better governance outcomes than those with limited state capacity and lower fiscal deficit.

Improving state capacity includes cleaning up the recruiting process for government jobs, increasing fixed costs, giving up informal levers of power, and eliminating rent-seeking by political networks. All of these are politically inconvenient for parties that are used to the convenience of low state capacity.

Low state capacity allows party functionaries to benefit from the state’s reputation and leverage political patronage for favours. Giving that up in states where it’s a norm is near impossible. This is most visible when there is a natural disaster. Party functionaries distribute relief material that is paid for by the state but the state has limited capacity to reach the last mile. In normal times the way this works is less in the face but more problematic as welfare measures in the last mile are impacted significantly by party structures.

Large states where there is an absence of state capacity to such an extent that they cannot even spend the allocated money indicate serious problems. For example, a state which cannot spend the money allocated to education but has a high dropout rate is going to be incapable of solving that problem in the foreseeable future. If it cannot even spend the money allotted, going over and beyond that to make up for poor enrolment is two layers removed.

One theory is that these states are possibly too large for effective administration. Another is that they do not raise enough of their own revenue, depend on central transfers, and therefore have low ownership, which translates to low capacity.

Improving governance at the local level is dependent on improving the manner in which the will of the people is communicated and understood. The way to achieve that is by extreme decentralisation rather than increased centralisation. However, the instinct of both the state and central governments has been to centralise more as a solution.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)