The National Education Policy 2020 seeks to move to a system where children learn in native Indian languages and not in English. After the explicit push for Hindi in the draft version of the policy was met with loud protests, the final version opted for an implicit push. The glorification and push for Sanskrit — a language that has been dead for centuries — survives in the final draft, though.

The Committee of Parliament on Official Language went one step further. Its deputy chairman, Bhartruhari Mahtab, said that “English is a foreign language and we should do away with this colonial practice” after submitting the committee’s 11th report to President Murmu.

This zeal for curbing English and batting for Hindi as not just a language to learn but as a medium of instruction in schools and colleges isn’t unique to the BJP. The Samajwadi Party has crusaded against English too, as have several other parties from various quarters over the years.

There are two distinct questions arising from this anti-English sentiment.

The first is, does it seek to eliminate English from emerging as a natural link language across India’s linguistically diverse states? Which is an implicit way of seeking or imposing, depending on whom one asks, that position for Hindi. States and people who don’t speak Hindi have legitimate political grievances about this, which has driven the politics of several states for decades.

The second and more pressing question for people living real lives far removed from the abstract ideas of political rights is: what are the material advantages of learning English or learning in English? And what are the disadvantages of not doing that?

The simple answer that does not require any fancy analysis is obvious — knowing English has a premium in India’s job market. But what is the extent of this advantage? And what are the implications for society? Is it true for a population as it is true for the individual?

Also Read: ‘India a superpower or not’ debate can wait, first answer this—how many new mothers live here?

English wage advantage

To examine the impact of learning English on a population, it can be useful to compare the wage rates and the use of English as a medium of instruction in that state or society.

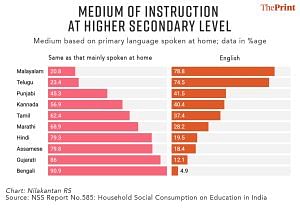

In states with the highest wage rates for non-agricultural labour —such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Punjab— children go to English-medium schools at a marginally higher rate.

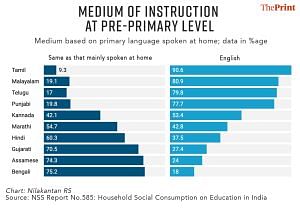

The data on the medium of instruction is drawn from the National Statistical Office’s survey on Household Social Consumption on Education in India, which considers the primary language spoken at home. We assume, therefore, that children speaking Malayalam, Tamil, and Punjabi are mainly in these respective states.

It’s also true that these three states are relatively wealthy, and so it is difficult to cite English as the sole contributing factor to their higher wage rates.

What makes a better case is the relatively poor wage rates in two prosperous states—Maharashtra and Gujarat— where the adoption of English as a medium of instruction lags behind these southern states and Punjab.

Only 28.2 per cent of Marathi-speaking children and a mere 12.1 per cent of Gujarati-speaking children attend English-medium schools at the higher secondary level. This percentage is lower than other states of equivalent educational and economic achievements.

And on cue, Maharashtra and Gujarat, despite being two of the three most industrialised states in the country, rank near the bottom in terms of wage rates.

There are exceptions, however. The Telugu-speaking population has one of the highest rates of English-medium education in the higher secondary level. Yet, the wage rates in Andhra Pradesh, for example, aren’t the highest.

This points to room for growth in the Telugu-speaking states, which may be due to a lack of industrialisation in Andhra Pradesh compared to its southern neighbours.

Similarly, Rajasthan, despite being considered a member of the infamous BIMARU club (an acronym for traditionally lagging states), has a relatively high wage rate. Karnataka, though, is a counter-example to the entire hypothesis. It’s an industrialised state with a high prevalence of English adoption, yet has poor wage rates.

Another way to look at this, is to examine how many pre-primary children are enrolling in English-medium schools, when compared to higher secondary students. This shows how the policy has been moving in more recent years.

Richer states, in general, have greater adoption of English. This, of course, does not mean that they got rich because they adopted English. But it seems that as they get richer, they do adopt English more.

This should tell policymakers that English is not only associated with material benefits, but also with the aspiration of populations to learn English and in English. The pre-primary and higher secondary data also show that all southern states are moving towards English-medium schools at a much higher rate.

Also Read: What FDI cheerleaders won’t tell you—UP has higher wage rates than Karnataka, Maharashtra

What do people want?

If the elite in a given society voluntarily opt out of learning in one language, it is but natural that the language in question will stagnate. If the best of cultural and scientific research output is not in that language, forcing ordinary people to learn it just to restore its lost glory is unfair. Worse, it affects their earning prospects in the process, as wage rates seem to suggest.

People learn new languages for a few reasons: economic value, assimilation, exploration of the lived experience of people who speak that language through literature, or because of cutting-edge research in that language.

Hindi doesn’t check all these boxes for everyone. Most other “Indian languages” listed by the NEP don’t, either. They don’t check any of the boxes for some people. What is the point then, of the NEP’s strange insistence on Sanskrit and Hindi? Or, as an afterthought, other “Indian languages”?

In a democracy, policymakers do not exist to impose their will on society, but to implement the will of the people. And the evidence suggests that people will generally choose a language that provides upward mobility. That language, it seems, is English. All of this makes the late Tamil Nadu chief minister CN Annadurai’s quote from the 1960s prescient:

Since every school in India teaches English, why can’t it be our link language? Why do Tamils have to study English for communication with the world and Hindi for communications within India? Do we need a big door for the big dog and a small door for the small dog? I say, let the small dog use the big door too! All that is needed is the big door. Both the big and the small dog could use it!

This quote is from an era when politicians were also scholars and spoke with a lot more colour. In today’s political climate, this quote will probably be branded as anti-national or anti-Hindi. But Annadurai’s sentiment is even more potent today, given his beloved Tamil people have come a long way since then, in economic terms, partly because they learned English at a higher rate than the national average. Maybe what the Marathis and Gujaratis need — even more than the Hindi-speaking population — is their own CN Annadurai.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)