Today in India, the Arab conquests of the 7th to the 8th centuries CE are confidently proclaimed as proof of “Islam’s” iconoclastic savagery. These, along with the later careers of Mahmud Ghazni and Muhammad Ghori, are generally believed to have destroyed the older cultures and religions that they came in contact with.

But the medieval world isn’t that simple, especially once we look beyond political and religious invective.

In fact, for a few decades in the 8th century, as the Abbasid Caliphate was being consolidated, a dynasty of former Buddhists from Balkh (present-day Afghanistan) ranked among the most powerful in the empire. They helped establish the Caliphate’s model for centuries and commissioned Sanskrit translations as well that spread from Kashmir to Spain. Their illustrious careers help us better understand the nature of medieval conquest—and how we should think about it today.

Iranian Buddhism

Just like the term “India”, “Iran” generally evokes the monolithic modern nation-state. But ancient India and Iran were both sprawling, diverse landmasses, home to many language groups, religions, cultures. In his excellent chapter, “The Bactrian Background of the Barmakids”, historian Kevin van Bladel brings this point across by examining the eastern portion of the Iranian world: Bactria.

We’ve visited Bactria before in Thinking Medieval, though not in the detail that it deserves. Defined by the upper Amu Darya river valley, encircled by mountains, Bactria (also known as Tokharistan) was at the most important crossroads in Central Asia, with connections into China, India, and Iran. Balkh, at the southern extremity, was its premier city.

Bactria had a distinctive political and religious culture and its peoples spoke Bactrian, an Iranian language. It was once the seat of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, and one of the major centres of the Kushan Empire in the 1st to 3rd centuries CE.

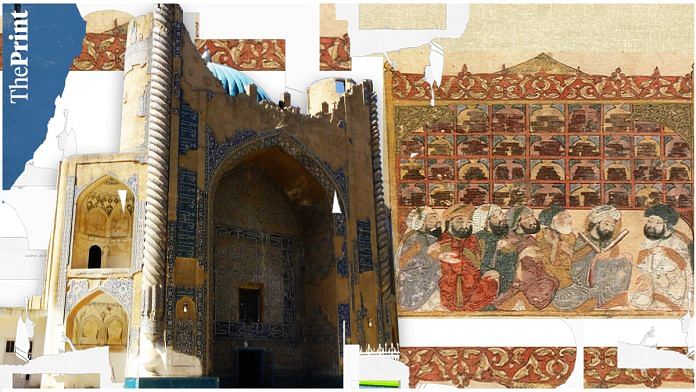

Buddhism flourished under the Kushan power, and networks of monasteries and stupas spread along the overland trade routes to China. Balkh itself hosted a colossal stupa and monastery called the Nava-Vihara, or the new monastery, adorned with gems and silk.

Intriguingly, as suggested by anthropologist Mostafa Vaziri in Buddhism in Iran: An Anthropological Approach to Traces and Influences, some of these networks may have extended toward the West. Many villages in present-day Iran bear the name Nawbahar–derived from Nava-Vihara–as well as Buddhan, Buddhiyan, and so on.

It’s not clear when this transmission happened. In the 3rd century at least, the Zoroastrian high priesthood of Iran’s Sasanian Empire was fairly inimical to Buddhism. Though the Sasanians eventually seized Bactria from the Kushans, it remained a frontier region, and Buddhism continued to thrive under subsequent waves of Hunnic and Turkic rulers.

From the 7th century onwards, the Sasanians were conquered by the Arabs in western Iran. By the 8th century, Arab armies had reached Bactria, and warred with its rulers for a few decades. The ensuing political chaos was advantageous to other invading powers, such as the Kashmiri king Lalitaditya Muktapida, who forced local rulers to pay him tribute. The king of Balkh fled as the Arabs moved in.

Bladel, analysing Bactrian documents, found that even with Arab governors present, most locals remained Buddhist and swore allegiance to local gods. Some of them converted to Islam and adopted Arabised names, but there’s no indication in Bactrian documents that they were doing so at sword-point. Bactria had seen many conquerors come and go; it was by no means inevitable that the Arabs would stay.

Also read: Manichaeism worshipped Jesus, Buddha. This Silk Road religion’s strength became its weakness

The Barmakid viziers

The Nava-Vihara at Balkh was an enormous establishment, drawing patronage from local rulers and the more distant Kabul Shahs. Its chief officials bore the Sanskrit title of pramukha, Arabised to barmak.

The barmaks were not monks—they were aristocrats, intermarried with important families.

As the region’s political fabric frayed during the wars of the 8th century, the Nava-Vihara’s wealth made it a target. A petty king massacred the barmak’s family, and one of his sons escaped to Kashmir. Here, the Karkota dynasty—flush with the wealth of conquest—patronised Buddhism, while keeping it subordinate to Vaishnavism.

Bactrians and Turks were part of the Karkota court. And, as Bladel writes, a young barmak studied medicine there before returning to the Nava-Vihara. With the Muslim name of Khalid, he joined the Caliph’s court as a healer, and an Arab garrison was established in Balkh.

Meanwhile, transformations were afoot in the Arab world. The vast Iranian plateau resented the supremacy of Arabs. Supported by an influential preacher from the region, a new dynasty, the Abbasid, came to power in the Caliphate. They would need a more cosmopolitan elite to rule their unwieldy empire. They needed men like Khalid, the barmak.

In the span of decades, the barmak’s family catapulted to the highest ranks of Caliphate nobility. According to the Encyclopaedia Iranica, as governors and generals, they put down rebellions and oversaw Abbasid campaigns against the Byzantine Empire. Barmakid men tutored the caliph’s sons; Barmakid women were their wet nurses.

The Barmakids even commissioned a history of their family, the Akhbār al-Barāmika wa-faḍāʾiluhum. Through this, they claimed that the Nava-Vihara had been built on the model of the Ka’aba in Mecca and that the name “Barmak” actually meant “in charge of Mecca” (abar Makka). Such claims helped the Barmakids legitimise their previous careers as powerful Buddhists. They justified their ownership of vast tracts of land around Balkh, and established themselves as the Eastern equals to the Western Quraysh tribe—the custodians of Mecca, to whom the Abbasid Caliphs were related, Bladel writes.

The reinvention worked. The barmakids were tremendously wealthy, and powerful, and maintained an active interest in their Bactrian heritage—and its connections to the Sanskritic world of Kashmir and beyond.

Yahya ibn Khalid, the vizier of the entire Caliphate, sent missions to India to collect texts and materials, and commissioned translations of medical treatises. He was the patron of many Indian scholars well-trained in Sanskrit literary theory. Scholars in Baghdad interacted with them, and fragments of translated texts travelled as far as Spain. Even Chanakya—rendered into Arabic as “Shanaq the great Indian”—was translated, for his expertise on poisons.

Also read: How a minor medieval war inspired a Telugu ‘Katha’, Tollywood movies

Muslims and Buddhists, or Arabs and Bactrians?

The Barmakids’ success was also their downfall. By 803, concerned about their overweening influence, the fifth Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid turned against the family and stripped them of their properties.

Some Arab poets claimed that this was because of the Barmakids’ interest in polytheism; others said it was because they attempted to marry an Abbasid princess. We have no way of knowing what happened. At the very least, we can say that the poets and historians who attacked the Barmakids had a job to do, just like the poets and historians they once patronised. And the end of the Barmakids did not mean the end of non-Muslims and non-Arabs in the halls of Caliphate power.

As Bladel writes, Greco-Roman scientific ideas had been popular before the Barmakids, and grew even more popular thereafter. While the eastern Iranian elites were no longer as prominent, Christians and Jews from Syria remained influential bureaucrats and doctors. Within a century, western Iranian warlords had assumed control of the Caliphate.

But what does this say about the interaction between Islam and Buddhism? Did the rise of the Barmakids indicate religious tolerance, and their fall intolerance? These categories don’t do justice to the complex power negotiations of the 8th century—the countless personal and public decisions that left little trace in the public record.

Intransigent religious categories don’t fit the nuance of the Bactrian documents, which show a gradual adoption of Arab ideas. Instead of talking about monolithic “Muslims” and “Buddhists”, it would be better to discuss Arabs and Bactrians, the interactions between complex groups. Blobs of colour on maps don’t capture the reality of medieval empires. Then, as now, empires were made of people—some more powerful than others.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)