Central Asian lords in tunics and boots, paying obeisance to Iranian, Greek, and Indian gods; stupas surrounded by image shrines, resounding to the chanting of verses in the now-extinct Gandhari language. The historical Buddha—who was active in just a small part of the Gangetic Plains—might not even have recognised the “Buddhism” being practised in the northwest of the subcontinent in the 1st-2nd century CE. But compared to our modern notion of a unitary “classical” India, which influenced the world, it was really from the highly diverse region of Gandhara that Buddhism, or to be precise Gandharan—not “Indian”— Buddhism, embarked on its global conquest.

Innovations in stupa worship

As we saw in the previous edition of Thinking Medieval, by the 1st century CE, the northwest of the subcontinent (Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwestern India) was in a state of cultural churn. “Shakastan”, a confederation of Indo-Scythian or Shaka families who intermarried with local powers, stretched from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in present-day Pakistan to Mathura in present-day India. Inscriptions reveal that many Shaka royals—including one queen Ayasia in Mathura—donated to the SarvastivadaBuddhists. Around the same time, her distant relative Senavarma, a ruler of the Odi kingdom in the Swat Valley, made a significant decision: He would dedicate a Buddhist reliquary to a stupa that he had renovated and expanded.

While stupa worship and the veneration of relics are integral to Buddhism today, it went through many evolutionary stages. On the Andhra coast, for example, it dovetailed with earlier practices of venerating the dead who were buried in megalithic structures. In the northwest, where waves of migration had created multicentric, multiethnic political systems, enterprising monasteries seem to have developed another approach.

By the 1st century CE, as epigraphist Professor Richard Salomon suggests in his paper The Inscription of Senavarma, King of Odi, that the stupa cult had become quite popular with elites. Here, Buddhist rituals allowed “merit” to be generated until the “end and completion of samsara”, the mortal universe, through the enshrining of relics in large stupas. And the patrons of such relics—usually wealthy political grandees—could then distribute merit to practically anyone they chose. “Merit,” thus, became one among many commodities exchanged as a tribute between vassals and overlords, which was perfect for the region’s politics. Indeed, this may well have been one of the reasons why Central Asian rulers in India took to Buddhism with such fervour.

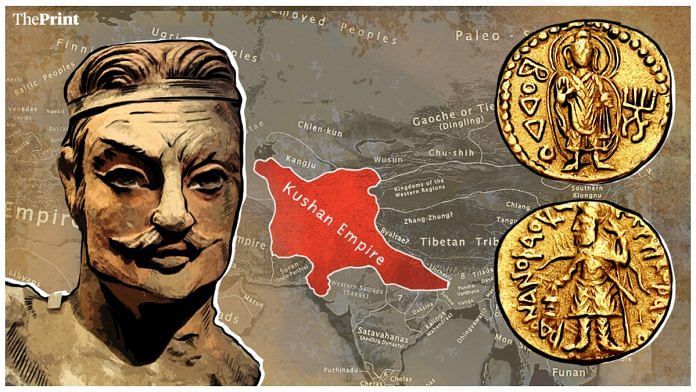

This makes the aforementioned donation of Senavarma, king of Odi, all the more fascinating. Though his family married extensively with the Shakas and, on occasion,paid them tribute, there is little mention of them in his donative inscription. Instead, the primary recipient of merit (outside his family) is one Sadakshana, “the son of the Gods, son of the Great King, King over Kings, Kuyula Kataphsa”. This was a sign of things to come, for the predominance of the Shakas was waning. Kataphsa was none other than Kujula Kadphises, known in Chinese as Qiujiuque, the founder of what would come to be known as the Kushan Empire: A new confederation that would transform Asian history.

Also read: India’s Buddhist nuns you don’t hear about: Landladies, loan sharks, merchants

The most important ancient empire?

The Kushans were the culmination of the many waves of migratory peoples who had settled and ruled in the northwest of the subcontinent over the previous centuries. By the 1st century CE, writes historian Jason Neelis in Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks, they had been united under the banner of Kujula, who adopted the title of “Kushana Yabgu [Confederation] steadfast in Dharma” and began to pressure the Shaka confederations in present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, corresponding to the edges of Gandhara, then known as Shakastan.

Within another century, Kujula’s grandson Kanishka had conquered most of Shakastan, made Mathura his primary centre of power, and subjugated all the mahajanapadas or “great countries” of the Gangetic Plains.

“By administering a network from the Oxus basin to the Ganges delta, the Kushanas effectively unified major nodes of the northern [trade] routes known as the Uttarapatha. Kushana administration of this artery of commercial and cultural exchanges facilitated long-distance movement of merchants and missionaries between South Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia,” writes Neelis.

This Kushan Empire was nothing like a modern nation-state, but that did not make it any less of a historical force. As American art historian John M. Rosenfield writes in his prologue to Gandharan Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, Texts, it controlled a few major strongholds, including Kapisha (near present-day Kabul), Purushapura/Kanishkapura (present-day Peshawar), and Mathura.

Trade arteries connected major strongholds, and the pressure of Kushan military power brought into its fold cities stretching “deep into present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It was probably also linked with the mountain kingdom of Kashmir and the city-state of Khotan in the western Tarim Basin [in China’s Xinjiang],” writes Rosenfield. Within this extraordinarily diverse network of peoples and polities, Rosenfield adds, “lived astronomers, mathematicians, theologians, playwrights, poets, grammarians, logicians, and physicians.”

It was Kushan domination, more than any Gangetic power, that truly led to Buddhism spreading out of South Asia into Central Asia in a great wave.

Also read: What we know as Indian Buddhism today was shaped by Central Asians and Greeks

Gandhari: Ancient Asia’s lingua franca

Kanishka issued coins marked with the Buddha (written in Greek script as ΒΟΔΔΟ), a clear sign that he wished to be associated with Buddhists. He and other Kushan rulers spread their patronage widely, encouraging the melding of diverse gods worshipped in their domains. There is little evidence that he was a Buddhist, though Buddhists went out of their way to claim him in later texts.

What there is archaeological evidence of is that Buddhism exploded in popularity, taking advantage of the stability offered by the Kushan Empire. Monasteries and stupas, once concentrated in the centre of the Gandhara region, now began to be established further and further out from the great node of Purushapura. A vast number of Kushan nobles and officers enshrined relics for merit (much of which was granted, ritually, to their overlord Kanishka). Clearly, the innovations developed by Buddhists a little earlier were well-suited for the new socio-political conditions of the Kushan superstate.

Over the last few decades, archaeological excavations in China, Afghanistan and Pakistan have also turned up caches of Buddhist scrolls written in the Gandhari language, discussed by Professor Salomon in his paper Gāndhārī in the Worlds of India, Iran, and Central Asia. Thanks to the predominance of the Kushans, Gandhari spread as a language of ritual, sacred knowledge, commerce and administration through much of Central Asia, an area known as ‘Greater Gandhara’. “Gandhari rose to this eminent if transitory rank by the time-honoured method: it had an army,” notes Salomon, rather drily.

It was Gandharan elites, Gandharan texts, Gandharan translators, and Gandharan Buddhist experts who transformed the region into an eclectic cultural powerhouse with the resources and the cultural institutions required to act (as Neelis puts it) as “a springboard” for the transmission of Buddhism into Asia at large. As noted earlier, the Buddhism that spread from Gandhara, with its emphasis on the stupa cult and completely new texts, would have been unrecognisable to the historical Buddha. It was a completely different cultural complex, with its only similarity to ancient Buddhism being the use of some basic conceptual terms. It was as distinct from the Buddha’s Buddhism as Eastern ‘Orthodox’ Christianity of the Byzantine Empire was from Jesus Christ’s Christianity, adapted to the needs of a diverse, cosmopolitan imperial elite.

When Chinese pilgrims began to travel back to South Asia many centuries later in search of original texts, Gandhara was seen as one of the religion’s central hubs, very much at par with the ancient sites deep in the Gangetic Plains. By the 2nd century CE, the Gandhari language had even begun to exchange words with various Iranian tongues native to Central Asia, indicating that it was spoken bilingually across a swathe of the continent.

Great changes were afoot. As we will see in future editions of Thinking Medieval, Gandhara, the most diverse part of the ancient world that completely confounds our modern notions of monolithic national pride, would go on to influence everything: From the new Mahayana Buddhism and emerging Indic notions of kingship to even Hindu gods and goddesses like Skanda and Durga.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)