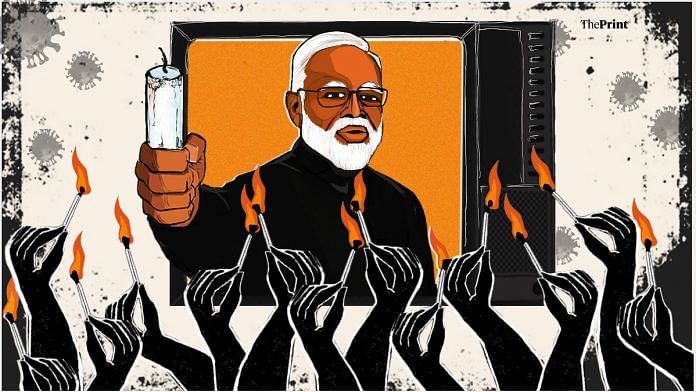

In the 2024 Lok Sabha election campaign, one of the arguments of the BJP has been that Narendra Modi is a strong leader who will make muscular and decisive policies as Prime Minister, while the opposition is a collection of regional parties with a relatively weak national party at the core, which will not be able to act with conviction and make strong-willed decisions.

Two important questions arise out of this claim: firstly, is that true? And secondly, even if it were true, is that desirable? The first question of who is stronger is one of political judgment. Partisans will offer their prejudice as judgment, which isn’t useful anywhere outside a TV studio. The second question is more interesting and instructive. What does strong leadership offer? Do decisions made with strength, which sounds like a euphemism for unilateral decision-making that lacks humility and consensus-building, have a place in a democracy? Even if they do, is that effective?

In the last 10 years, the decisions that stemmed from such decisive political leadership — demonetisation, GST implementation, abrogation of Article 370, the three farm laws that were subsequently revoked, as well as the overnight imposition of a nationwide lockdown — have ranged from disastrous to being a mixed bag at best. With hindsight, even Prime Minister Modi would probably agree he would not rush these decisions through if he had to do it again. Their utilitarian impact has been blighted by the lack of consensus afterward and a lingering suspicion that these decisions will be rolled back when the politics changes.

Which is why the question really is: what do we want in a democracy? Quick and decisive action that may not have political consensus or frustratingly slow decision-making that endures long after the decision is made?

Also read: Why the Modi government gets away with lies, and how the opposition could change that

Strong leader—anti-democracy

The basic purpose of a democracy, if one were to take a step back, is clear: it is the slow-moving consensus because democracy’s purpose is not the correctness of outcome but system stability. It doesn’t matter how good, enlightened, or exalted the Prime Minister is or made out to be. The entire reason we have a parliamentary system is to ensure we do not let the Prime Minister become a Philosopher King that Plato imagined, or for that matter, a king of any other kind. If strong leaders worked better than slow-moving consensus building, we would still have had a Soviet Union!

In the modern context, we see the parliamentary system as both more just and more effective compared to an enlightened philosopher king or a Stalinist dictator. It’s useful to restate why we think that, as a society, if we want to break the myth of a strong leader. It is just in the sense that we do not like the concept of a king, philosopher or otherwise, because we imagine a society in which all (wo)men are created equal and want our government to represent and respond to us. And it yields better results because we have come to understand that the wisdom of crowds generates better outcomes over the long term for things that aren’t an exact science. It is counter-intuitive but crowds beat experts, be they philosopher kings or overpaid fund managers, almost every single time. Our financial system, the backbone of our modern capitalist order, is built on that assumption.

Even if the wisdom of crowds weren’t a true result, we would still settle for a system where we do not have a philosopher king. We now think of it as a problem worth having, even if the solutions to side-step it are not easy or elegant. We would like our governments to be a reasonable reflection of who we are as a people because we think of all humans as equal. If that reflection ends up as less than ideal, we wish to change ourselves and not the reflection. And we certainly don’t do that through an enlightened philosopher king sitting “above” us. We, therefore, have a Westminster system where Parliament is supreme; not the Prime Minister. And we elect our Members of Parliament and therefore a government. We do not elect Prime Ministers directly. We do all this in the hope that our government is a just representation of us. A strong leader is the antithesis of that!

Also read: Who’s snatching your gold, mangalsutras? RBI data says it’s Modi

India has a wicked problem

Democracy is hard. There’s no good way to elect a government that perfectly reflects the will of the people. Even small countries with ethnically and linguistically homogeneous populations struggle with it. The scale of that problem tests the limits of credulity in a country that is as large, as diverse, and as populous as India is. Governments in post-colonial states have an added problem, given their boundaries are often not natural units of civilisation but contain in them the limits of empire, bureaucracy, and ambition.

India, with a population of 1.3 billion that has multiple ethnic, religious, linguistic, and developmental divides, with histories of conflict among stakeholders, has a wicked problem on its hands. The structure of administrative power for such a large and diverse population cannot be unitary; but as a corollary, the absence of that unitary structure will raise questions on the country’s raison d’etre. This is exactly where self-declared strong leaders come in. They offer themselves as a solution to the complicated status quo; and the frustration over the status quo, which is slow by design, makes the strongman sound like he has a point.

However, it’s always useful to remind ourselves of the basics. The purpose of a government is to be a tool of convenience for the people who elect it and not be a thing unto itself. Unitary power structures, especially in large and diverse countries with significant minorities, often end up being that. These then neither reflect the will of the people nor do they actually achieve what they claimed they will achieve — better utilitarian results. It’s like we make a bargain with the devil for nothing.

A classic example is India’s complex, complicated, and intractable problems in health, education, and agriculture. Kerala, for example, has health metrics that are comparable to OECD countries. What it needs now is a focus on output metrics and improved high-end care. Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and much of the Indo-Gangetic plains have health metrics comparable to sub-Saharan Africa. What they need is a focus on input metrics. A strong leader who offers a single solution — by virtue of heading a strong government in Delhi that usurps states’ rights — to both these sets of states is claiming to achieve what’s mathematically impossible.

In education, again, the Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) of Kerala and Tamil Nadu are far ahead; meaning these states should now focus on quality of education. Whereas states in the Indo-Gangetic plains, with low GER, have to get kids into school first. They can focus on quality later! A strong leader who comes up with the same policy for both sets of states, in the name of ‘one nation, one policy’, is being unjust to both sets of states.

A necessary condition to achieve a responsive government in such a situation is: make governments that are farther away from people less impactful and less decisive compared to governments that are closer to people. In other words, strengthen state and local governments and moderate the influence and ability of the Union government.

A ‘strong’ Prime Minister is a hurdle in that.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

Good article! There is a need for a federal structure of governance than a strong leader!!

Mr data scientist, you have a hidden superiority complex of south India. In most of the article you went in length about how we strive to be equal. Then all of a sudden u started showing your disdain about North India and its people and how south deserves ‘special’ treatment.

What do u think south Indians are superior to North Indians because south is more developed. And your word like “unnatural units” definitely implies that. Historically, We have pushed dravidians to the south of the Indian subcontinent. We have seen largest empires of India. We have also protected the south from other foreign invasions from the North.

South India is more developed because of your long coastline and natural resources. Coastal regions are economically more favourable compared to land locked regions. These geographical regions are more conducive to trade and Industry and exchange of knowledge. This geo-economical advantages have provided the south with more access to foreign trade and foreign ideas including foreign languages. Southern peninsula act as a stop point for historic trade routes of west and south east Asia and china. This geographical advantage is even more pronounced for Sri Lanka, so they are doing even better than south India. So if you think that south is more prosperous because dravidians are wiser, then u r a fool.

Democracy main role is that, we need an unbiased governing body for capitalism to thrive like in America. No other type of govt seems fit for that. However China has been able to do that, without being democratic. Diversity is an impediment not a blessing. Most people confuse between variety and diversity. The former is desirable the latter is an obstacle.