There are at least two areas of economic regulation in agricultural markets in which the Narendra Modi government agrees with the Manmohan Singh government. First is the frequent use of the Essential Commodities Act to check inflationary trends in the food economy. The second is the distrust of future markets for price discovery of agricultural commodities.

The table below shows the suspensions imposed on future trading by various governments in India.

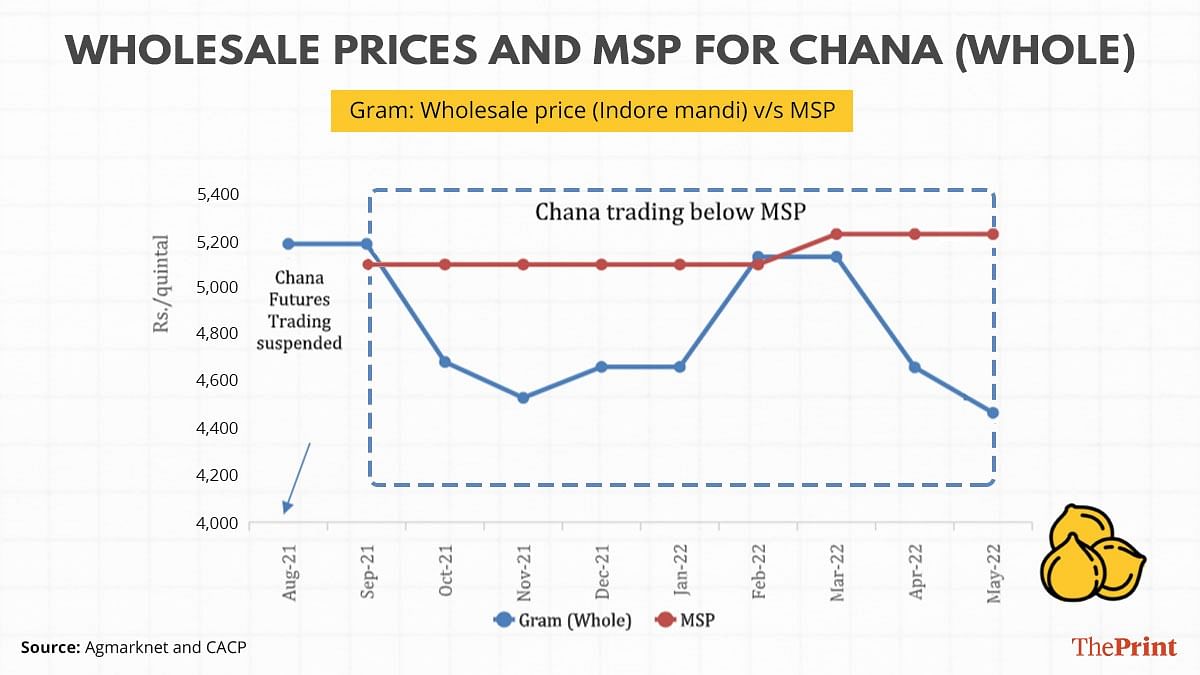

On 16 August, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) decided to suspend, till further order, the launch of any new contract of chana and mustard seed on commodity exchanges. The decision was not due to high inflation in chana. In fact, the market price of chana in Madhya Pradesh, a major producing state, was about Rs 4,500 to Rs 4,800 per quintal against the MSP of Rs 5,100 per quintal. In the past one year of the ban on future trading in chana, the prices have mostly remained below MSP.

Figure 1

The bigger hammer on futures trading, however, had come in December 2021 when the SEBI barred the commodity exchanges from launching futures contracts of seven agricultural commodities for one year – paddy (non-basmati), wheat, chana, mustard seeds and its derivatives, soya bean and its derivatives, crude palm oil and moong. Even in the running contracts, new positions were not allowed and only the squaring-off of existing contracts was permitted.

In the cases of wheat, moong and paddy (non-basmati), the trading volumes were insignificant even if these contracts were available on the exchanges.

Also read: India has a dal problem – open import policy is hurting prices and farmers

What bans have done to Indian future trading

It must be noted that in December 2021, the lower size of the wheat crop was not anticipated and in fact, India was expecting to harvest a bumper crop. As late as April-May 2022, senior functionaries of the government were not only encouraging the export of wheat from India but also believed that the country can fill up the gap in the global supply of wheat created due to the Russian war on Ukraine, which resulted in complete stoppage of Ukrainian wheat.

During the peak sowing period of the kharif crop (June-July 2022), farmers had no clue about the expected prices of their crops at the time of harvest. Despite the non-availability of price signals, the farmers have maintained the area under soybean at last year’s level while the area under tur, moong and urad has come down (as of 19 August 2022).

As a result of the ban on future trading, the processors of commodities—for example, the soybean oil manufacturing units—are not able to hedge their supplies against the fluctuation in prices. Moreover, they have to depend on mandis (spot markets) for supplies. Another result of frequent restrictions and bans on future trading in commodities is that the commodity exchanges have not been able to develop to their full potential, even though India and China have similar commodities on future exchanges. For example, sugar, soybean, palm oil, and rapeseed are major commodities on Chinese future exchanges too.

Globally, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) is the largest commodity exchange in terms of quantities traded. In case of corn, as of March 2022, open interest on CBOT (number of active or outstanding contracts) was about 56 per cent of the 348 million tonne of corn produced in the US. In case of soybean and its products, open interest was 33 per cent of production. China’s Dalian Commodity Exchange has about 18 per cent open interest in corn. For soybean meal, it was 25.8 per cent.

Due to frequent bans and restrictions, the Indian futures market has not developed to its full potential and, in 2022-23, due to suspension of contracts till December 2022, the turnover of agricultural commodities on exchanges has drastically reduced.

Also read: Inflation pinching your pocket? There is more in the pipeline. But god can help

Time to lift the ban

Media reports suggest that the Modi government is considering a reduction in import duty on wheat (currently 40 per cent) so that private flour mills of south India can replenish their stocks. Wheat inflation is in double digits at both wholesale and retail levels. It is quite ironic that the importers will use the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and other exchanges to hedge their supplies.

In the last few years, the Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) have also taken to using commodity exchanges for hedging and selling their produce. Even though the number of such FPOs is very small and the quantity traded is negligible, there is a need to empower them so that they can also take the benefit of modern instruments of price discovery and trading in commodities.

From time to time, by using the Essential Commodities Act, the government makes it mandatory to declare the stock of essential commodities (such as pulses and oilseeds in recent years) with traders, wholesalers and even retailers. If the registration of warehouses with the Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA) becomes compulsory, this cumbersome procedure for declaration of stocks will not be required.

One hopes that a considered decision will soon be taken by the Modi government and SEBI to lift the ban on future trading of agricultural commodities. The ecosystem envisaged by Warehousing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2007 has not developed to the desired level as registration of warehouses with WDRA is still not compulsory. Trading in agricultural commodities stored in the warehouses can also be formalised by using electronic negotiable warehousing receipts (NWRs) rather than the physical receipts issued by warehouses.

Hussain is former Agriculture Secretary to the Government of India. Saini is an economist. They have promoted Arcus Policy Research, a think tank on economy. Views are personal.