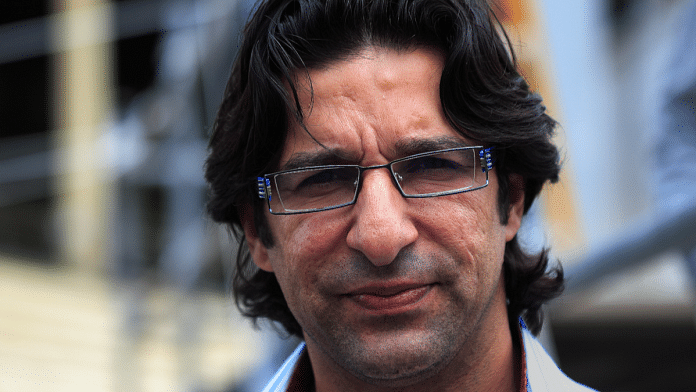

The recent incident in which former Pakistani cricketer Wasim Akram used a casteist slur on live television after the Pakistani cricket team’s shocking defeat against Afghanistan has put the spotlight on a deeper issue that plagues the country. It is a nation still struggling with a feudalistic social structure and a dearth of democracy. And Akram isn’t the first to have displayed blatant casteist bias — a popular Pakistani maulana, too, has done so in the past.

In all likelihood, there will be no action against Akram, as there is no law in the country that penalises citizens for making such remarks. The whole uproar is on this side of the border, where such derogatory language by popular figures is met with swift legal action. This disparity marks the foundational differences between the two nations in their approach to democracy and social justice.

The foundational divide

Pakistan’s political landscape is dominated by a single meta-narrative — the perennial conflict between the military and civilian government, with the former exerting significant influence over the latter. In an ideological sense, Pakistan evolved as the antithesis to India: All its internal challenges, especially social and gender issues, are subdued so that they do not threaten the religious foundation of the nation.

The power dynamics in Pakistan have perpetuated a system wherein feudalistic structures persist. Its rulers, media, and academics also dismiss any allegations of caste atrocities. But the truth remains that Pakistan is a caste-divided society like India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

Shaista Abdul Aziz Patel, assistant professor of Critical Muslim Studies at the University of California, San Diego, has written in Al Jazeera that out of approximately 40 castes in Pakistan, 32 were officially designated as scheduled castes under the November 1957 presidential ordinance. She further writes that a significant portion of the Christian population in Pakistan is the Dalit community, often derogatorily referred to as ‘chamaar’.

She cites a recent article in The New York Times highlighting the plight of Dalit Christians in Pakistan. “In July 2020, the Pakistani military placed newspaper advertisements for sewer sweepers with the caveat that only Christians should apply,” the report reads. The 1998 census revealed that while Christians constituted merely 1.6 per cent of the total population, they disproportionately filled 80 per cent of the sweeper positions.

Also read: 2 reasons why SC, ST, OBC do not reach the top in civil services—UPA…

Contrasting Indian experience

It’s not that India has freed itself of caste-based discrimination. Manual scavengers are still choking to death in sewers and Dalits have been victims of caste atrocities to this day. But things here are way different than in Pakistan. India has a legal and constitutional structure in place that protects Dalits against caste-based discrimination and violence.

Its diverse Constituent Assembly, under the visionary guidance of BR Ambedkar, laid the bedrock for a liberal democratic foundation of the country. The Constitution, with equality enshrined in its Preamble, abolished untouchability through Article 17 and instituted social justice and reservation through Articles 15, 16, 330, 332, 340, 341, and 342. We have various special Acts like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act of 1989 to protect depressed classes. The National Commission for Scheduled Caste is a constitutional body that acts as a redressal forum.

When former cricketer Yuvraj Singh used a casteist term in a conversation on Instagram, he faced severe backlash. Legal proceedings were initiated against him, and he was arrested. The cricketer later issued a formal apology. Similarly, actress Munmun Dutta faced serious repercussions after using an inappropriate term in a video. The incident prompted immediate action from law enforcement authorities, which initiated an investigation into the matter. She is now on bail. Actress Yuvika Chaudhary, too, issued an apology for using a casteist slur on a public platform.

These incidents underscore India’s commitment to ensuring that derogatory language, especially of casteist nature, is met with stern consequences.

Also read: Modi’s Women’s Reservation Bill has an OBC-sized oversight. Undermines inclusivity, fairness

Catalysts for change

Political mobilisation and democratic upsurge also played a crucial role in battling caste in India. Due to his poor health and differences with the Congress, Ambedkar couldn’t do more in his quest to eradicate caste-based inequality. But the baton was successfully taken up by a young scientist in Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), popularly known as Kanshi Ram. His political heir Mayawati’s ascent to the position of chief minister of Uttar Pradesh marked a watershed moment in India’s pursuit of social justice and equality. As a self-made Dalit leader, her journey was a testament to the power of resilience, determination, and steadfast commitment to the upliftment of marginalised communities.

The largest state in India with a significant population of ‘lower’ castes, UP presented an enormous platform for Mayawati to enact meaningful change. Her term in office not only shattered traditional power dynamics but also redefined the narrative surrounding caste discourse in India. Mayawati’s leadership served as a powerful symbol of hope and empowerment for Dalits and other groups that had long been relegated to the fringes of society. By occupying the highest political office in the state, Mayawati demonstrated that political wit and competence could beat caste-based biases.

More importantly, her administration implemented a series of policies aimed at addressing the historical injustices faced by marginalised communities. Mayawati inspired a new generation of activists and leaders, including Chandrashekhar Azad of Bhim Army, encouraging them to believe in their agency and potential to effect change.

Mayawati continues to serve as a beacon of hope and a powerful reminder of the progress that can be achieved through visionary leadership.

No Ambedkars and Mayawatis in Pakistan

Regrettably, Pakistan’s political landscape lacks such inspirational figures. Instead, it is dominated by military generals who are more or less like feudal lords presiding over a stagnant social and political system that breeds casteist individuals like Akram.

The historical context of the treatment of depressed classes in Pakistan is a stark picture of systemic discrimination. This reality was glaringly evident during the Round Table conferences of 1930-32 when Muslim leaders, who later played instrumental roles in the formation of Pakistan, chose to align with ‘upper’ caste Hindus.

Moreover, the grassroots struggle against caste discrimination in India was strong enough to effect policies such as the Poona Pact, which was a compromised yet significant achievement for marginalised groups. Lower castes were promised reserved constituencies and jobs. This happened only because the struggle was sustained by the depressed sections.

In the erstwhile West Pakistan, there was no leader advocating for the rights of these communities like Ambedkar did in India. To bolster their Muslim identity and strengthen their bargaining power, Muslim depressed classes often suppressed their caste identities. This choice, while potentially advantageous to the Muslim cause at a macro level, ultimately came at the cost of the interests and well-being of the depressed sections.

Meanwhile, the plight of Hindus (predominantly Dalits) in East Pakistan after 1947 exemplified the dire situation. Realising that it was far from a safe haven for them, millions of Dalit Hindus underwent painful migration to India in search of a more inclusive and tolerant society. Jogendra Nath Mandal, the first law minister of Pakistan, was one such individual who made this difficult choice. His resignation from the Pakistan cabinet and migration to India later on served as a poignant testament to the harsh realities faced by marginalised communities in the neighbouring country.

Ambedkar had even anticipated such a predicament for Dalit Hindus in Pakistan. He had advised them not to convert to Islam and instead, return to India. With respect to forced conversion, he said: “We Scheduled Castes must look upon it as a last resort forced upon them by violence. And even to those who are converted by force and violence, I say that they must not regard themselves as lost to the fold forever. I pledge my word that if they wish to come back, I shall see that they are received back into the fold and treated as brethren in the same manner in which they were treated before their conversion.”

Today, Wasim Akram’s use of a casteist slur only serves to affirm Ambedkar’s prescient counsel.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. He tweets @Profdilipmandal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)