Madhya Pradesh is at the cusp of a change. Will the assembly election finally trigger it? Will a political change pave the way for a deeper and much delayed social turn in the state? Or are we in for another phase of political manoeuvring that serves to protect the dominant social and economic interests that have ruled the state since its formation? That is the real question to ask of the ongoing electoral contest in MP — which appears closer than warranted.

The change has been stalled for a very long time, confined to a few glimmers once in a while. The state’s northern neighbour Uttar Pradesh underwent a Dalit upsurge in the 1990s, which entered the northern belt of MP via the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) but subsided very soon. Its eastern neighbours — Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh — have witnessed the dominance of Adivasi politics. With a 21 per cent Adivasi population in MP, one should expect the same pattern in the state. But the rise of the Gondwana Ganatantra Party (GGP) was stymied and managed by bigger political forces.

MP has more than 50 per cent Other Backward Class (OBC) population but has not witnessed Mandal politics. The state is presented as the success story of agrarian transformation in the last couple of decades. However, farmers’ organisations have not left much imprint on state politics, despite their agitation following the firing in Mandsaur in 2017.

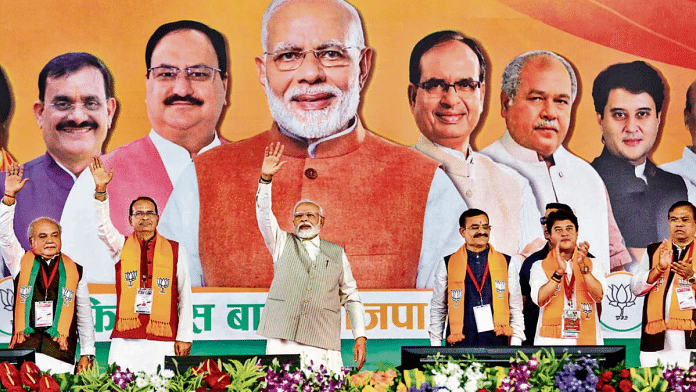

18 years under the BJP

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s continuous electoral success and political dominance in the country for the past two decades has put a lid on this simmering pot of social churning. Since 2003, the first election after Chhattisgarh was carved out as a state, the BJP has been in power, though its popularity has declined consistently in every assembly election. In 2018, it lost the election to the Congress by five seats, but Kamal Nath’s 15-month government was ambushed via the infamous Operation Kamal to bring the BJP back to power with support from defector Jyotiraditya Scindia.

Frankly, the party does not have much to show for its long rule. MP has performed poorly on several socio-economic indicators. There were close to 39 lakh registered unemployed in the state at the start of 2023. Recruitment to government jobs is riddled with delays and scams. Despite an improvement in agricultural production, the state ranks fourth in the country when it comes to farmer suicides. Feudal caste oppression continues unabated — the crime rate against Dalits in the state is two and a half times the national average.

On the health front, MP ranks a poor 17 out of 19 on the Niti Aayog’s index. It has the worst infant mortality rate in the country and faces severe shortage of doctors. Despite such a poor track record, the BJP has continued to rule, thanks to its deep organisational base that goes back to Jana Sangh days and to the weak machinery of its main rival, the Congress.

Also read: India has gone into data discomfort. Explains silence on Bihar caste inequality

Churning below the radar

This election promised to be different. The burden of 18 years of incumbency and non-performance was beginning to tell. There has been a visible fatigue with ‘Mamaji’ Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the incumbent CM. The Congress, meanwhile, had everything going for it. In a state where the party has traditionally been severely faction-ridden, it been more united than ever because of the undisputed leadership of Kamal Nath during the last five years. The Congress also enjoyed public sympathy for being cheated out from the backdoor after winning the election in 2018.

At a deeper plane, forces of social churning have been active below the radar. MP witnessed among the strongest Dalit protests against the dilution of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act in 2018, leading to another wave of Dalit activism. A new generation of Adivasi leadership has come up under the banner of Jay Adiwasi Yuva Shakti (JAYS). Despite splintering, the various factions of JAYS represent the rising aspirations of the Adivasi youth seeking to overthrow the older leadership. And there has been a quiet OBC upsurge in Madhya Pradesh — not limited to ‘upper’ OBCs — led by organisations like the OBC Mahasabha. The nation-wide farmers’ movement of 2020 had its echo in Madhya Pradesh too.

All these movements are anti-establishment in instinct and against the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and BJP in ideology. It was for the Congress to harness this new social energy and become a political vehicle for social change. Therefore, this election in Madhya Pradesh was the Congress’ to lose.

However, that is not what the polls show. We have tracked a total of 16 surveys in MP since June. Eight of them placed the Congress close to or above the majority mark of 116 seats and seven showed the BJP to be ahead. Only one outlier survey by Cfore predicted a Karnataka-like majority for the Congress. Taking all the polls into account, irrespective of when they were done, the BJP’s average vote share comes to 44 per cent, while the Congress’ settles at 43 per cent. The average seats projected for the Congress are, however, more at 117 and for the BJP, 110.

It would be silly to use such a split survey verdict to make a confident forecast about the outcome. These surveys cannot be taken as the gospel truth. They were somewhat off last time too. At any rate, the projected difference between the two parties is well within the normal margin of error that any survey carries. All we can say as of now is that the Congress appears to have an edge in a contest that is closer than it appeared a few months ago. But it does not look like a knockout of the incumbent, which appeared a real possibility till a couple of months ago.

Also read: Does India need a ceiling on election expenditure? We’re better off without this fiction

Has the Congress done enough?

So, it looks like one of the few elections where the outcome is decided during the campaign. The Congress has run a virorous campaign in the state since August, highlighting the failures of the Chouhan government, especially on economic matters such as the state’s mounting debt, youth unemployment, paper leaks, rigging in the recruitment process (Vyapam/ESB), and the condition of farmers. The state Congress leadership has also borrowed from the Karnataka election playbook by accusing the BJP government of being a “50% commission government” and shedding light on various corrupt practices such as the Patwari recruitment scam and the substandard construction of the Mahakal Lok Corridor. In fact, the party unveiled a document called the Ghotala Sheet in August, listing as many as 254 scams that allegedly occurred during the 18-year-long BJP rule in the state.

But the Congress may not have done enough to tap into the deeper social churning that could have given the BJP a crushing defeat. While its share of OBC tickets has gone up to 65 this time (up from last time, but about the same as the BJP now), upper-caste dominance within the party continues. The Congress leadership has raised the issue of caste census and has promised 27 per cent job reservation for the OBC, but this is not yet a major issue in this election. The Lokniti-CSDS survey shows that a plurality (44 per cent) of voters support the idea of a caste census and only about a quarter (24 per cent) were in opposition, a significant chunk (32 per cent) did not offer any opinion on the issue. The survey finds that while the Congress is holding on to its Dalit vote base and improving its position among Adivasi and Muslim voters, it trails the BJP by a big margin among the OBC voters.

The BJP appears to have come back in the contest by recognising the anti-incumbency mood against the Chouhan government. It has remained ambivalent about its chief ministerial candidate. The PM does not even mention Shivraj Singh by name in his election rallies. The sitting CM, on his part, is heavily relying on women voters to secure his position. Since October, approximately 1.3 crore underprivileged women aged 21-60 years have been receiving Rs 1,250 in their bank accounts under the Ladli Behna Yojana, an increase from the previous Rs 1,000 instalment announced in March 2023. In fact, a fresh instalment was deposited into their accounts on 7 November, just 10 days before the voting day. The Congress has pledged a Nari Samman Yojana, promising women Rs 1,500 per month along with LPG cylinders at Rs 500.

The polls suggest that the BJP enjoys a small lead among women voters, not the kind of decisive lead it may have hoped for. The BJP, of course, has its organisational strength in this state that it can always bank upon.

What we can be sure about

While the Congress appears to be ahead, one cannot rule out both parties ending up with a similar vote share. In that eventuality, the outcome will depend upon how the votes translate into seats.

Here, the Congress has an advantage. In 2018, the Congress actually trailed the BJP by 0.1 per cent but picked 5 more seats than the BJP. This time, polls indicate a bigger urban-rural divide that might favour the Congress. According to the CSDS poll, the Congress leads the BJP in rural areas by a margin of 5 percentage points, while the BJP is estimated to be way ahead in urban areas by a massive 20 percentage points.

These estimates need not be accurate, but they indicate a possibility. There are far more rural seats in the state (175-200, depending on how a ‘rural’ seat is defined) than urban ones (30-55 seats). Even if the BJP were to sweep the urban areas with big margins, the Congress would still be in a position to overtake the BJP on the back of smaller margins in a large number of rural seats. In 2018, the Congress just had just 1 percentage point vote lead over the BJP in rural MP, and yet it won 16 more rural seats than its rival.

While we cannot be sure of the nature and the margin of the verdict, we can be sure of one thing: The impact of the outcome will be disproportionately bigger than its margin. Not only will it impact the mood and equation for the 2024 Lok Sabha election, but it will also decide the trajectory of social change that is waiting to happen in Madhya Pradesh.

Yogendra Yadav is National Convener of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Shreyas Sardesai is a survey researcher associated with the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)