First we had an x-ray, now we have an MRI. If the first round of caste ‘census’ data in Bihar established that caste count was possible and useful, the second tranche of data has established beyond doubt that a nationwide caste census is essential to combat social inequalities in today’s India. To those who needed evidence, the recently released data from Bihar demonstrates that caste matters. Caste continues to be a determinant of educational opportunities, a robust indicator of economic status, and a gateway to decent employment opportunities.

Predictably, no one wants to look at this data. The entire debate on pros and cons of caste census focused not on the census but on the merits and demerits of reservation. Now that the data has been released, the focus is on the 65 per cent quota. Or on a casual (though ill-thought and indecent) remark by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, so as to hijack the entire debate away from the real issue of caste inequalities. As and when the media has bothered to report the findings of this ‘census’, it has focused on some perfunctory or generic data on Bihar‘s poverty or levels of education. Such data has always been around. No one seems to be interested in the fresh data on caste inequalities. Should we be surprised?

Let us begin by understanding what is really new about this caste census data in Bihar. The first tranche of data released last month—the X-ray—had offered jaati-wise population estimates that were not available since 1931. It established that backward castes—BC as well as EBC—numbered much more than expected. And the dominant ‘upper castes’ were numerically much smaller. The data released this week—more like an MRI—provides jaati-wise socio-economic profile.

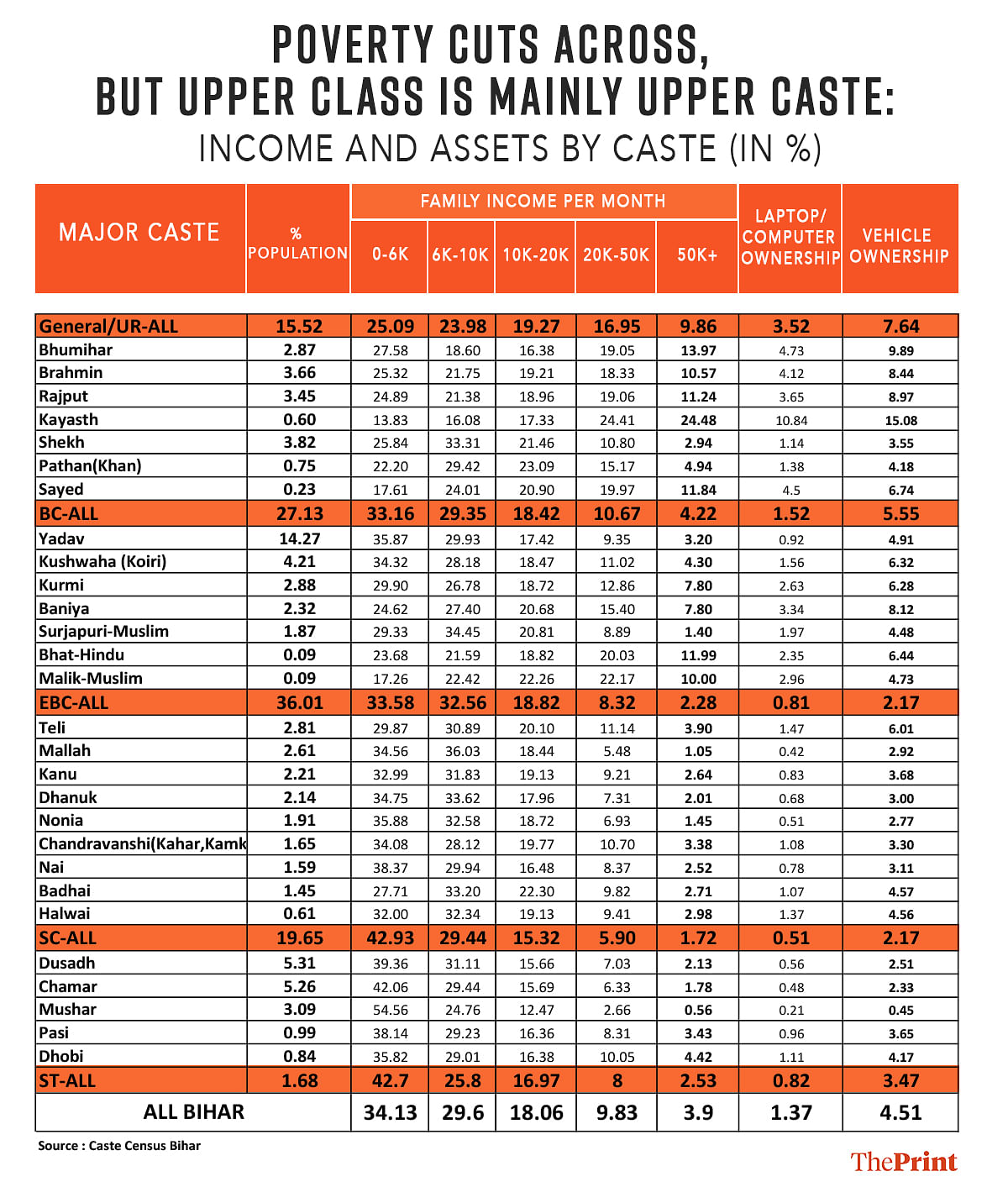

The data on the economic condition of each household is a textbook pattern of correlation: the lower the caste, the lower the economic status.

Specifically, the recent data provides economic status by way of family income, ownership of vehicles and computers, educational level of each member of family, and employment status for each person. All this data is available by each caste group and for each jaati separately. Though it has not been released, yet this break-up should be available for each district, each bloc, each village, and indeed for each family. This is a goldmine of sociological information that will be used by policy makers and researchers for decades to come. Since this data is not limited only to backward or disadvantaged sections and includes the ‘upper’ caste as well, we have for the first time a social profile of three dimensions of privileges in terms of economic status, educational attainments, and employment secured. You could call it E³.

Also read: Bihar census identified privileged and under-privileged castes. Go national now

A goldmine of socioeconomic data

The data on the economic condition of each household presented in Table 1 is a textbook pattern of correlation: the ‘lower’ the caste, the lower the economic status. This is true of all caste groupings (General, BC, EBC, SC, ST), and it is true within each of these caste categories. Since much of the analysis is based on self-reported family income (which can be dodgy since people tend to under report), we need to double check it with data on ownership of vehicles (from two-wheeler to six-wheeler) and computers (with or without internet). At the lower end of the income spectrum, we find poverty distributed across all caste categories. Even among the ‘upper’ castes, one-fourth are very poor, with a family income of less than Rs 6,000 per month. The proportion increases gently to 33 per cent among the BC and EBC, and 43 per cent among the SC and ST.

The slope is very steep when we look at the upper end of economic privileges of those who report Rs 50,000 or more as their family monthly income. The proportion of these ‘rich’ families is just around 2 per cent for SC and EBC. It rises to 4 per cent for the BC and shoots up to 10 per cent among the General or the upper caste. This trend is corroborated by the data on laptop ownership (a proxy for material educational opportunities) and vehicle ownership (a proxy for economic assets). Interestingly, among the upper caste, the richest are the Kayasthas and not landed communities like Bhumihars and Rajputs. Among the OBCs, the numerically largest group of Yadav is substantially poorer than Kurmis or Banias (who are BC in Bihar) or even the Kushwahas.

The caste-wise data on education shows an even sharper slope than the economy. Table 2 focuses on degrees that provide some chance of a decent job. These include postgraduate degrees like MA, MSc or MCom along with engineering or medical degrees and higher qualifications like PhD or CA. Here the impact of centuries of caste privileges and prohibition on learning are very stark. A Dalit in Bihar is ten times less likely to obtain any of these quality degrees than the upper castes. The difference is staggering if we look at various jaatis. Of every 10,000 people, 1089 Kayasthas (traditional literary community) possess these employment-worthy degrees. The corresponding figure for Musahar, at the lowest rung within the Scheduled Castes, is just 1 out of every 10,000 persons.

Interestingly, Bhumihars are more educated than Brahmins, though the proportion for both is less than half of the Kayasthas. The traditional savarna/shudra divide continues to filter educational opportunities. The proportion of Backward Castes with high degrees is less than one third of the General category. The proportion among the EBCs is less than half of that among the BCs. There are very serious disparities within the BCs. Yadavs stand at 0.82 per cent while Kurmis are three times higher, at 2.4 per cent.

One critical insight of this census relates to the internal division within Muslims. The data on economic and educational status confirms that Syed Muslims are quite like the Hindu ‘upper’ castes, though Sheikhs and Pathans appear to be miss-classified as ‘General’, because their economic and educational profile fits in more with the ‘backward class’ category. Malik Muslims, who are currently classified as BC, approximate the economic and educational profile of the General category. This demonstrates the relevance of caste census for fine-tuning the reservation policy.

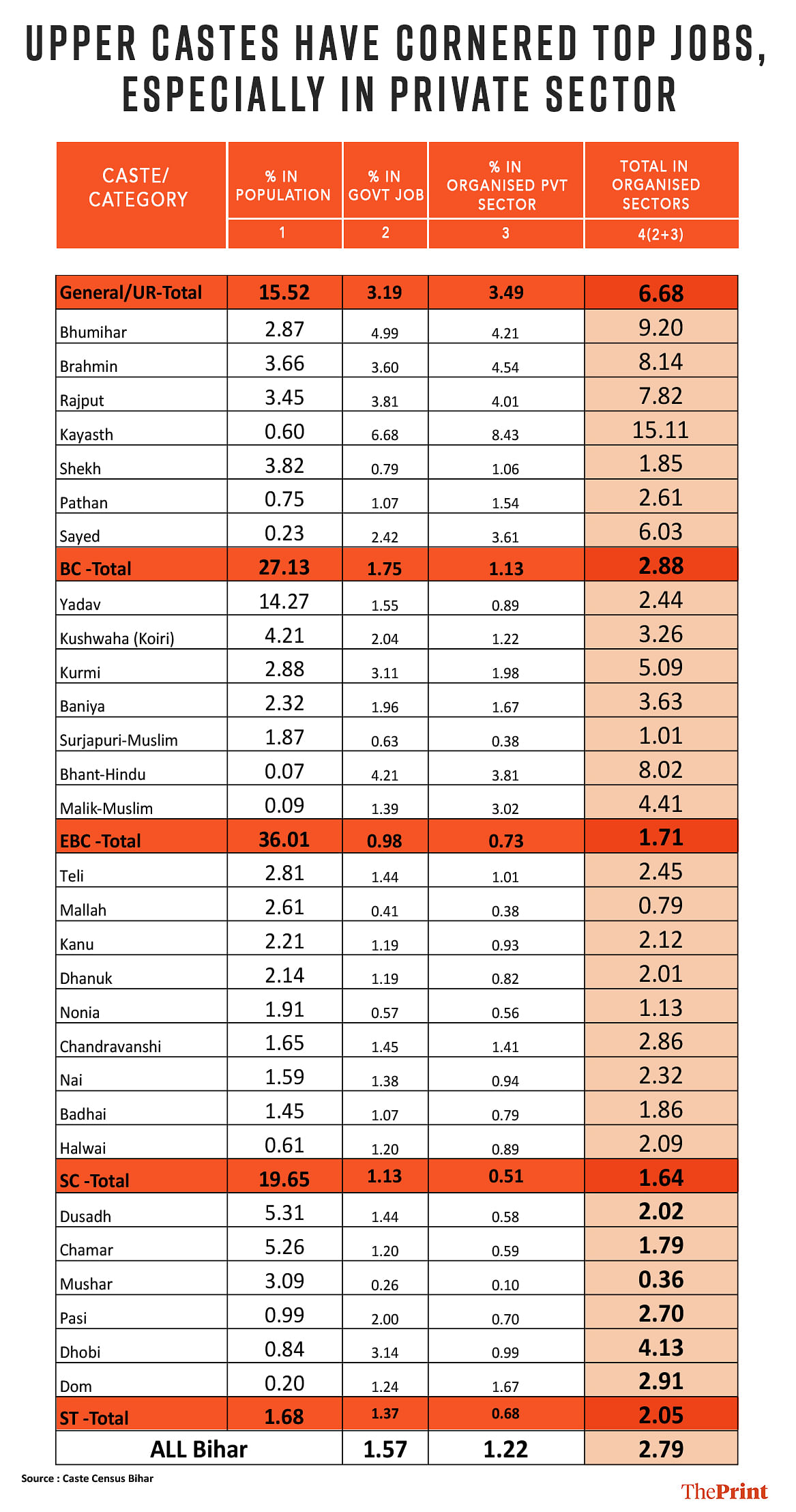

Finally, let us turn to jobs. Disparities in the economic and educational opportunities that we noted above reflect directly in the occupational profile presented in Table 3. Less than 3 per cent of Bihar‘s population is employed in the ‘organised sector’ jobs with regular salary, PF, and perhaps pension. This proportion is nearly 7 per cent among the upper caste but drops to 2.8 per cent among the BCs and 1.7 per cent among the EBCs.

The break-up of organised sector jobs between government jobs and private sector jobs shows a clear contrast. The ‘upper’ castes have cornered disproportionately bigger share in both these categories, still higher in the private sector. Here, again, the Kayasthas outstrip everyone else in the proportion of government as well as private sector jobs. The Backward Caste share goes down in the private sector. Within the broad grouping of OBCs, the upper segment (that is the BC in Bihar) have cornered more jobs than the numerically larger segment of the EBC. A comparison of the proportion of Dalits, who managed to get organised sector jobs in the government sector (1.13 per cent) and in the private sector (less than half at 0.51 per cent) is a neat illustration of what the condition of Dalits would have been if they had no advantage of reservation in government jobs.

Let us all absorb and understand this data before we launch into a debate on enhancement of OBC quota. And let us all demand a similar X-ray and MRI for the entire country.

Yogendra Yadav is among the founders of Jai Kisan Andolan and Swaraj India, and a political analyst. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)