If the proof of the kheer is in the eating, the first spoonful of caste data from Bihar “census” proves why we need a nationwide caste census. Driven by ‘upper caste’ anxiety over possible increase in reservation for the backward groups, the Indian media has focused on Bihar caste survey’s political motivation and fallout, rather than the data. But the very publication of the data is a fitting response to those who said such an exercise is not feasible.

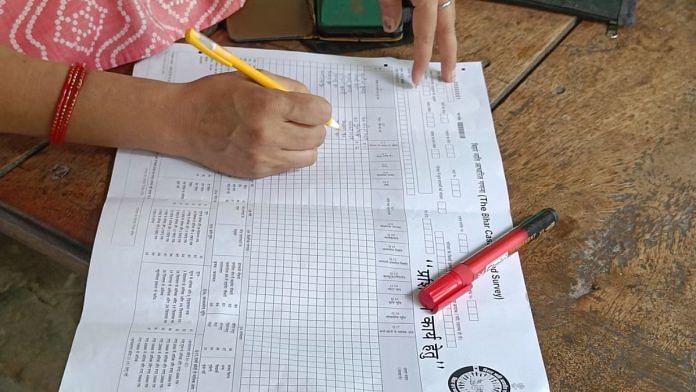

The first tranche of data released by the government of Bihar simply lists 209 castes and provides their population, also aggregated by caste categories and religion. While we wait for the second and more substantial data instalment, the tables released so far already advance our understanding in several respects. It answers those who asked whether such a count was of any use.

First of all, it does what the non-existent Census of India 2021 should have done– provide the population total for Bihar, which was 10.41 crore in 2011 and was projected to be 12.68 crore in July 2023. We now know the exact number: 12.53 crore. (The figures released by Bihar Government are based on 13.07 crore Biharis, including 53.7 lakh who reside outside Bihar). Not much surprise here.

Second, the survey updates the data about the population share of three big social groupings: Scheduled Castes, Schedule Tribes, and Muslims. As compared to 2011, the share of SC population has gone up from 16% to 19.65%, ST from 1.3% to 1.68%, and Muslims from 16.9% to 17.7%. This shows that the population and population share of the ST and SC have undergone a steep increase since the last census. The increase is muted in the case of Muslims. This information is new and useful, but could have been obtained if the Census of India, due in 2021, was held on time.

Third, and this is where it gets interesting, the caste survey provides the first robust data on the share of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the population of Bihar. Now we know it is 63.14%, substantially more than the mythical national figure of 52%. For professional surveyors, this is not entirely a revelation. The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO)’s Consumer Expenditure survey of 2011-12 estimated OBC population at 60% while the more recent All India Debt and Investment Survey of 2019 estimated it at 59%. The last two rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) under-estimated it at 54% and 58%. The CSDS-Lokniti election surveys of 2020 were fairly accurate in estimating the OBCs in Bihar: 61%. But for the general public, the new number is likely to raise a serious question: if Economically Weaker Sections, a sub group of the 15.5% General category, can be given 10% quota, why limit 63% OBCs to just 27% quota?

Also read: India needs caste census more than Chandrayaan-3. SC verdict on Bihar caste survey shows why

The real jati-wise break-up

Fourth, we now have a clear sense of the relative strength of the two sub-categories within the OBcs. The ‘upper’ group–the “Backwards” comprising mainly land-owning peasant communities like Yadav, Kurmi, Kushwaha, etc–add up to 27.12%. The ‘lower’ segment–the “Extremely Backwards (EBC) comprising over a hundred small caste groups involved in service, handicraft, and manual work–have a population share of 36.01%. This was generally known–and is broadly in line with the reservations for the two groups at 18% and 12% respectively–but the exact numbers are still something to be reckoned with. This would help shift the spotlight of Bihar politics and policy on the EBCs.

Fifth, we now know that the residual category, “General” or the unreserved, comprises merely 15.52% of the state’s population. For seasoned observers and survey researchers, this is no big shock (though the number is lower than the survey-based estimates of around 18-20% that I used to believe in). But the publication of authoritative figures brings into sharp relief the oddity of this expression called “General”, which invites us to think of itself as the norm, while everyone else is an exception. We now recognise that the unreserved category is a tiny exception. This category includes some Muslims who are not OBCs.

Finally, we have the first real jati-wise break-up of Bihar’s population since 1931. There are many surprises for keen observers of Bihar politics and society. Brahmins and Rajputs were believed to be around 5% or more; they are actually 3.67% and 3.45%. Bhumihars were estimated to be between 4 and 5%. They are only 2.89%. So, in all, the ‘upper caste’ Hindus, the Savarna or the Agde, are (including 0.6% Kayasthas) merely one-tenth of the state’s population, 10.61% to be precise. This represents a sharp decline from 15.4% in 1931. Scholar and IIM professor Chinmay Tumbe shows that the reason for this decline in the ‘upper caste’ Hindu proportion is partly lower population growth, but mainly the dynamics of migration. The relatively privileged communities have exited Bihar, while those at the bottom of the heap are condemned to stay back. This is what also explains the rise in the population share of SC, ST and Muslims.

This break-up shows that some of the dominant OBCs were also over-estimated. Some estimates had put Yadavs as 15% or more, but their actual share is 14.3%, up from 12.7% in 1931. Kurmis were estimated to be 4% or more, but are only 2.9%, down from 3.3% in 1931. The really big caste groups, after the Yadavs, are Ravidasi (5.3%), Dusadh (5.3%), Kushwaha (4.2%), Musahar (3.1%), Teli (2.8%), Mallah (2.6%), Bania (2.3%; they are OBCs in Bihar), Kanu (2.2%), Dhanuk (2.1%), Prajapati (1.4 %), Badhai (1.5%), Kahar (1.6%) and so on.

The caste-wise picture is not limited to Hindus. This is the first official enumeration of Muslim communities in Bihar. We now know that Ashraaf communities like the Sheikh (3.8%), Syed (0.2%), Mallik (0.1%), and Pathan (0.7%) constitute a very small proportion of Muslims. Three-fourths of the Muslims in Bihar are “Pasmandas” comprising various backward communities like Julaha, Dhunia, Dhobi, Lalbegi, and Surjapuri. This should give a fillip to politics of the Pasmanda, first brought to notice by Ali Anwar’s path-breaking work Masawat ki Jung: The Battle for Equality.

Also read: Caste census data on expected lines — why it changes little in Bihar politics

More revelations on the way

We now wait for the second instalment of the data, promised in the next session of Bihar assembly. Besides caste and religion, this official survey in Bihar also collected information on education, occupation, land ownership, monthly income, and assets like four-wheeler and computer. For me, this would be the most valuable yield of this survey, as it would provide the real profile of socio-economic and educational backwardness for each jati group separately, something we have never known.

We do have some rough estimates. Bihar journalist Srikant has maintained a systematic record of the caste profile of various assemblies and ministries in the state. Sanjay Kumar’s book Post Mandal Politics in Bihar also contains valuable data from official and no official surveys. In 1985, for example, the ‘upper caste’ Hindus (whose population is just 10.6%) controlled 42% of the assembly seats. By 2020, it had come down, but was still 26%, more than double their share in population. Now the Yadavs control a disproportionate share in the assembly, about 21% compared to their population share of 14%. We know that the proportion of big farmers who own more than five acres of land was twice as much among the “General” castes as compared to the OBCs. Only 9.2% of General castes were agricultural labour, while the proportion was 29.4% among the OBCs and 42.5% among the SCs. The educational gaps were equally stark: the General category had 10.5% with graduation and above, while the proportion was 2.8% among the OBCs and 2.1% among the SCs.

But this available data is very sketchy and for very broad categories. The next tranche of data from Bihar would provide us, hopefully, with a granular picture of how different jatis have done within these broad categories, especially within the umbrella category called the OBC. The real point of the caste census was not merely the overall population share of different communities but the profile of privileged and under-privileged for each caste. That is essential for fine-tuning the politics and policies of social justice. While we can debate which party or caste would be its immediate beneficiary, there is no doubt that in the long run, this data would help the EBCs and Pasmandas—the micro communities that have been invisibilised so far.

Dr Ambedkar’s goal of annihilation of caste cannot be achieved by closing our eyes to the existence of caste and caste-based inequalities. Elimination of caste-based inequalities cannot begin without recognising, counting and measuring the effects of caste. Now that we know it is possible, useful and desirable, the entire country must follow Bihar’s lead.

Yogendra Yadav is a political scientist and national convener of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. He is also a co-founder of Jai Kisan Andolan and Swaraj India. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)