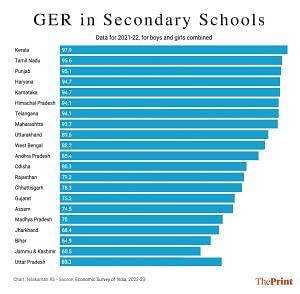

Uttar Pradesh has a problem. Among large states, it has one of the lowest Gross Enrollment Ratios for secondary schools in the country. And the state is not just doing poorly compared to Kerala, which has near-universal enrollment rates at this level. UP, at 69.3 per cent, is among the bottom four states in terms of secondary school GERs. It’s shocking, in this day and age, that a significant number of children in India’s most populous state are not in school at a school-going age.

If states are to be ranked on governance, this alone would rank UP as one of the country’s worst-governed states. Simply because getting children to school, at scale, is not just about building institutions. It’s about their overall health, their nutrition, the economic circumstances of their parents, the expectations that parents have for their children, the safety perception that parents have about society in general, the ability of the state to hire good teachers, and so on. It takes failure in all other allied areas of governance, along with failure in education policy, to have so many children of school-going age not attend school.

It’s easy to point to the state’s current administration and pin the entire blame on it. But for a state of this size and a problem of this magnitude, it is an issue that transcends election cycles and needs policy solutions that will bear fruit on a generational time scale. In the meantime, UP must focus on addressing this problem above all others. Doing that is a necessary condition for us to give the incumbents the benefit of the doubt in good faith. If they are at least doing what they can, we can let them do that and not hold them responsible for the hopeless situation they find themselves in. But are they?

Also read: Why doesn’t Maharashtra complain about allocation like South Indian states? Allocation ratios

UP’s relationship with education

The quickest rule of thumb to evaluate UP in terms of understanding whether the administration is doing its job is this: A state that is ranked among the absolute worst in such an important metric should at least be spending much more than the others, in relative terms, when it comes to education in its budget. The hope is that this additional spending in the present, with sacrifices in other areas, will hopefully move things in the right direction by building the capacity to bring more children into school over time. People elect governments exactly to make difficult choices like these.

UP, though, has done the opposite. It has been spending lower, not higher, than the national average on education as a percentage of its overall budget expenditure. In the budget for 2023-24, UP estimates to spend about 13 per cent of its overall expenditure on education. The national average is 14.8 per cent. But a more telling comparison is Rajasthan – another poor state in the set of states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and UP) sometimes referred to as BIMARU – which has allocated 19.5 per cent of its overall expenditure to education. This difference in spending isn’t meaningless; it shows up in the metric above as Rajasthan has a 79.2 GER in secondary schools as opposed to UP’s 69.3.

One of the problems that UP has, which complicates an already difficult situation, is that it still has an above-replacement fertility rate. This means that for each successive year, there are more and more children who are at school-going age compared to the previous year. This stands in stark contrast to states where the population has stabilised. For example, in Tamil Nadu, there are fewer children of school-going age each year as opposed to previous years because it has had a below-replacement fertility rate for over a generation. While every data point demands that UP spend more on education, the state bafflingly spends less than the national average despite needing those investments the most.

Also read: Rajasthan leaving BIMARU company. On health, education it won’t listen to Yogi, Shivraj

It’s time to do better

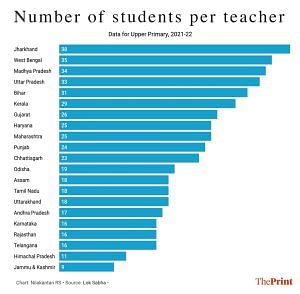

One data point that makes this additional need for investment in education important is the number of students per teacher. It’s one thing for states with a relatively high GER – like Kerala or West Bengal – to have a high number of students per teacher. They are operating at full capacity while their demand for services, owing to a falling fertility rate, is likely to decrease yearly. But the story is wildly different in the case of UP, where many kids aren’t even in school, and the fertility is still above replacement. A high number of students (33) per teacher points to the system already bursting at the seams while being nowhere close to serving even existing capacity, let alone a growing one.

The ways in which this issue manifests is sometimes tragic. A teacher ill-equipped to teach students asking one child to beat another as punishment, possibly with some religious bigotry thrown into the mix, can be viewed through this prism. This teacher was teaching at a private school and seems to have had very little training without much (or any) supervision. She exists as a teacher in UP because of the state’s extreme mismatch between demand and supply when it comes to education. She wouldn’t be allowed to teach in most other places in the world.

UP isn’t spending more on recruiting more teachers. It isn’t spending more on training them. It isn’t spending more on building more schools operated by the state. And these poorly trained teachers in badly run private schools, behaving in shocking ways toward students, happen to affect the child who does go to school. For every such child in UP, there is another who is not even in school.

The citizens of UP probably need to ask themselves and their government some difficult questions and hold both themselves and their government accountable. Bigotry happens in the absence of education. Individuals sometimes do bigoted things. But what happens when a teacher acts in such ways? That points to there being a problem with who gets to teach and where children go to learn. And how many such places exist.

Do better, UP. Spend on your children; they will repay you with dividends.

This author has updated the data from an earlier version to reflect accuracy.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)