Today Hindu goddesses are recognisable the world over. The goddess Kali, for example, inspired the Rolling Stones’ famous logo. Generations of films and TV shows have explored the mythology of Parvati and Durga. Millions of pilgrims visit sites associated with them. But in the Deccan 1,000 years ago, the community of goddesses was much more diverse. Jain divinities like Jvalamalini, ‘she who is garlanded with flames’, were worshipped by monks and kings, propitiated with elaborate rituals, and held sway in great temples. This is their story.

Who were Jainism’s goddesses?

Jainism today is best associated with tirthankaras: legendary ascetics believed to have conquered the senses, who purged themselves of negative karma and achieved the ultimate liberation. But it’s not entirely focused on liberation. As theology professor Ollie Qvarnström writes in his paper ‘Stability and Adaptability: A Jain Strategy for Survival and Growth’, medieval Jains conceived of divinities as operating in different ‘levels’ or worlds. Goddesses like Jvalamalini and Padmavati accompanied the middle world and underworld respectively, and were subject to the laws of karma just like mortals. Tirthankaras were entirely liberated and resided at the top of the universe. They helped with transcendental goals, like liberation achieved through austerities. Goddesses helped out with more mundane matters.

Jain communities may have venerated such deities from very early in their history. As Jainism expert Robert Zydenbos writes in ‘The Jaina Goddess Padmāvati in Karnataka’, texts from the last centuries BCE claim that Mahavira, the founder of the religion, avoided Vedic sacrificial grounds. He instead preferred to reside in the forest glades of yakshas and yakshis, male and female nature spirits. Yakshas were popular, independent deities in ancient India; all the major religious traditions—Hindu, Buddhist and Jain—tried to appropriate them. In South Indian Jainism centuries later, the term yakshi became interchangeable with ‘goddess’. In South Karnataka, it even became a popular name for women: Historian RN Nandi notes in Religious Institutions and Cults in the Deccan, that medieval inscriptions mention ladies called Yakkisundari, “beautiful like a yakshi”.

Over centuries, religious ideas flowed between non-literate communities and the literati of monasteries and courts, across religious and linguistic boundaries. It’s important to remember that though we call these goddesses “Hindu” or “Jain”, the distinction might not have been as clear to medieval worshippers. Some goddesses might have been functionally independent, even if Jains claimed they were the attendants of this or that tirthankara. Here’s an example of a local goddess being transformed by Jain masters.

In the late 8th or early 9th century CE, the Jain guru Helacharya developed the scriptures of the fierce Jvalamalini. One of his disciples recorded this story, discussed by historian John Cort in ‘Medieval Jaina Goddess Traditions’. Helacharya, we are told, was a tantric practitioner, and one of his female initiates was possessed by a demon. He climbed a hill where an ancient local fire goddess lived and received a powerful mantra from her. She drove out the demon, and her mantra served as a basis for Helacharya’s new tantric Jain cult. That’s how a local fire-goddess was elevated to the royal Jvalamalini.

Jain tantra was perfect for devotees’ worldly needs. Masters could use magical diagrams to cure disease and interrupt black magic. They could gain control over their enemies or put them to sleep by repeating mantras, turn invisible using talismans, drive people insane, and even attract women. Nandi discusses a recipe for this, from a Jvalamalini text. Cloves, saffron, cardamom, red arsenic, white lotus, sandalwood, basil, and other ingredients were to be ground by a girl’s hands, mixed with cold water and applied to the practitioner’s forehead. Another text, dedicated to a fierce form of the Jain goddess Padmavati, even provides recipes for aphrodisiacs, and advises men to tie to their waist the right thigh bone of a cat—supposedly to help them last longer in bed.

Also read:

Goddesses and the king

Goddesses were beautiful, powerful and frightening, and so they often received the attention of political figures. No less than three important Deccan kingdoms claimed that Jain goddesses were involved in their founding. The Gangas, around present-day Bengaluru and Mysuru, claimed from the 8th century that their ancestor’s preceptor was a Jain guru, who summoned the goddess Padmavati and received from her a magical sword. (Nandi, Religious Institutions.)

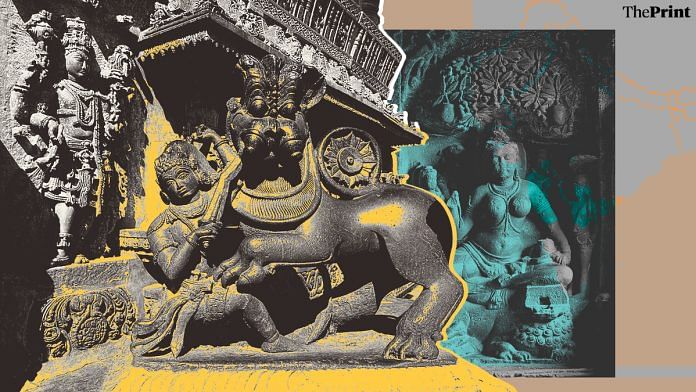

In the same region, the 11th-century Hoysala dynasty—best known for their spectacular Shiva and Vishnu temples—claimed that Padmavati took the form of a tiger and pounced on their founder, a hero called Sala. Sala’s Jain guru yelled “Smite, Sala! Poy, Sala!”, which he did; in a single blow, the tiger’s form fell away and Padmavati, pleased with the hero’s spunk, granted him kingship. (Zydenbos, ‘Padmāvati’.)

Padmavati worship moved west, and she was claimed in the 9th century by the Santara dynasty of the Western Ghats (around present-day Shivamogga, Karnataka). Forced to flee Mathura by a jealous stepmother, the dynasty’s legendary founder, Jinadatta, was believed to have picked up a golden idol of Padmavati, and arrived with her in the Ghats. The hill people there accepted him as king. Padmavati instructed Jinadatta to touch iron bars to her image, transforming them into gold. Jinadatta became prosperous, and one day he was gifted two pearls by a fisherman. He gave the larger one to his queen and the smaller one to Padmavati. This, understandably, annoyed the goddess, and turned her gold idol into stone and ceased its magical properties. (Cort, ‘Traditions’.)

As Zydenbos notes, all of these traditions reveal personalities: “Stories about Padmāvati tend to be magical, not straightforward, with an unexpected twist.” Jvalamalini’s legends, in contrast, depict her as ferocious and straightforward; she often helps out Jain monks in their attempts to outdo their rivals. Another goddess, Ambika, is maternal, a protector of children and kings alike. Yes, Jainism’s exemplars are renouncers, but the religion is so much more than that. The anxieties and ambitions of medieval Deccan people survive not in the great ascetic figures but in the humbler, vivacious female goddesses. They were not as exalted as the saintly men perhaps, but closer to hearts and homes.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)