Embedded in the rock more than 25 metres below the snow-dusted heart of the city, the cavern is now an empty hall, sometimes hired out for concerts and exhibitions. Seven decades ago this summer, the hall became home to a nuclear reactor that silently produced weapons-grade plutonium, the heart of one the world’s most secret nuclear weapons programmes. After Hiroshima, military experts had warned that the new kind of bomb dropped on the city would transform warfare. Workers’ shovels soon began hitting frozen earth.

The hall wasn’t under one of the Soviet Union’s secret nuclear cities – which began being constructed after dictator Joseph Stalin’s atomic spies informed him of the Manhattan Project – or in the wastes of China’s Lop Nur. It wasn’t under the Fontenay-aux-Roses in Paris, where France had begun to breed plutonium, or run by the discreetly named Tube Alloys, the British nuclear weapons programme.

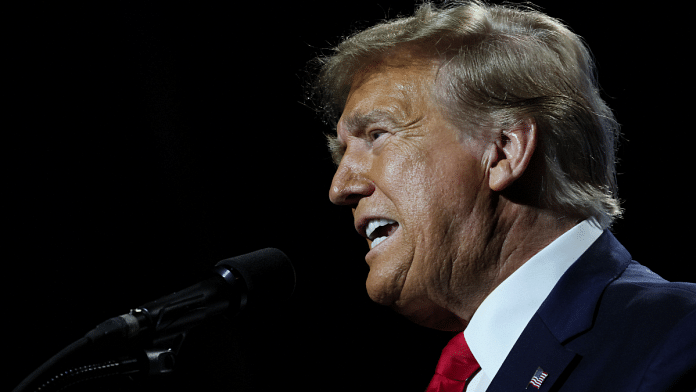

Largely forgotten, the story of Reaktor R1 in Stockholm—the capital of social-democratic free-love-and-sandals Sweden—helps us understand the security dilemmas facing Europe. Earlier this week, former United States President Donald Trump threatened to blow up NATO if its members didn’t pay more into the world’s largest security alliance.

Trump’s threats, as his former National Security Adviser John Bolton notes, will lead American allies across the world to begin wondering how credible the superpower’s security guarantees really are. “Well,” Bolton observed, “if Trump is willing to knife NATO, what makes anybody think he wouldn’t knife Israel if it suited his purposes?”

The question is even being asked in Sweden, which is in the middle of a long diplomatic battle for NATO membership. European leaders likely know what they might have to do if NATO does fall apart—but it’s not a prospect any of them will embrace.

The secret reactors

Less than two weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima, neutral Sweden’s armed forces, on 17 August 1945, asked for “an account of what might currently be known about the atomic bomb.” Led by the eminent physicist Torsten Magnusson, Sweden’s National Defence Research Agency began conducting preliminary studies into the elements of nuclear weapons. Within a decade, the country had acquired the technological foundations needed to begin work on an actual nuclear weapon.

Early in the summer of 1954, international relations scholar Thomas Jonter reveals, Magnusson gave a speech to top military commanders: “Because of the great advantages of atomic bombs from the point of view of defence, it is my opinion that sooner or later, we will have to seriously consider manufacturing them.”

Two years later, Sweden began tests on the special conventional explosive system needed to trigger a nuclear detonation.

As the Cold War freeze set in, similar efforts had begun across Europe. The United Kingdom had made major contributions to kickstarting the Manhattan Project. Leaders in the UK, official history records, expected that the US would return the favour by sharing technology after the end of the Second World War. Fearing the technology would leak to the USSR, however, American President Harry Truman declined to cooperate.

Furious, British politicians ordered resources available for the acquisition of an independent nuclear deterrent in 1946. “We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs,” Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin told the cabinet committee in charge of the project. “We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack flying on top of it.”

Across the English Channel, France was arriving at the same conclusion, and for much the same reason. The French government had acquired much of the world’s heavy water supply in 1940 and moved it to the UK. Physicists Lew Kowarski and Hans von Halban later conducted experiments that proved fission—and thus nuclear weapons—was possible.

Later, in 1944, the French scientist Jules Guéron, one of three involved in the Manhattan Project, gave leader-in-exile Charles de Gaulle a one-on-one secret briefing on the new weapons, nuclear policy expert Mycle Schneider records.

The limited American commitment to its allies, demonstrated in the early stages of the anti-colonial war in Vietnam, together with a commitment to autonomy in international decision-making, pushed France to decide to build its own nuclear weapons, international relations scholar Bruno Tertrais notes. Even today, French nuclear forces remain outside of NATO’s structure.

European leaders understood the constraints that would govern the US in the event of a future war. Crudely put, the US might not be willing to sacrifice New York or San Francisco for the sake of Paris and London. True deterrence could only be exercised by the nations that controlled how nuclear weapons would be used, and when.

Also read: Before US elections, Iraq is forcing America to answer—which ‘forever war’ is worth fighting

A European bomb?

Trump has rarely let facts intrude on arguments, but his criticism of NATO isn’t wholly off the mark. Last month, the defence committee of the UK parliament cast severe doubt on its ability to sustain a high-intensity war beyond a week, while the division-strength force Germany has committed to the alliance isn’t battle-ready. Thirteen of 31 NATO partners still do not spend the 2 per cent of GDP threshold agreed to in 2006, including Germany, let alone the 4 per cent Trump is demanding.

Leaving aside four small states of Eastern Europe—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland—America spends a greater share of its GDP on aid to Ukraine than members of NATO, research by the Kiel Institute shows.

This reflects the reality that European countries see the threats on their borders, and their vital interests, in significantly different ways—one of the important reasons independent nuclear weapons programmes sprang up after World War II.

Even though Swedish scientists had the contours of a nuclear weapon ready by 1965, and the military leadership was supportive, political clearance to build the bomb was never obtained. According to Jonter, this meant dropping the Swedish military’s hopes and plans for a 100-bomb arsenal, capable of devastating Soviet forces that might be on its borders.

This thinking wasn’t unique, though. Tiny Switzerland, journalist Michael Fischer notes, had begun conducting nuclear weapons development along with Sweden. Even though Switzerland was compelled to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1969, its bomb programme was not officially shut down until 1988, with the end of the Cold War.

In November 1957, historian Massimiliano Moretti records, France even signed a secret deal with its World War II enemies, Germany and Italy, to collaborate on nuclear weapons research. French nuclear doctrine weaponised ambiguity, retaining the right to a first strike on enemy targets, and introducing the concept of an explosion to demonstrate to enemy forces that they had reached their nuclear red lines.

Though De Gaulle had dropped the idea of France-Italy-Germany nuclear weapons cooperation by 1958, it doesn’t take much to appreciate the extraordinary concerns that drove it. The historian Maurice Vaïsse noted wryly that Europeans saw nuclear arsenals as “protecting oneself from one’s allies, not as arming oneself against one’s enemies.”

Also read: South Africa’s genocide case against Israel is crucial. Future wars need legal sanctions

A post-American Europe

Will such a Europe be as stable as an America-led NATO was able to provide? There’s no telling, but a second Trump Presidency may leave the world with no choice other than to find out. Doom, of course, might not lie ahead. The capacity of nuclear weapons to cause annihilation, the scholar Kenneth Waltz argued, “lessen the intensity as well as the frequency of war among their possessors. For fear of escalation, nuclear states do not want to fight long or hard over important interests—indeed, they do not want to fight at all.”

Emmanuel Macron, the French President, has long pushed for a European security architecture, casting the EU as a third superpower after the US and China. There is no clarity, though, on how France—the only nuclear weapons state in the alliance—would provide deterrence to the bloc, though.

Likely, several of Europe’s countries would have to rethink their decisions to abandon nuclear weapons programmes in the 1960s, at a screwdriver’s twist from having usable arsenals. Similar trends might be realised in Asia, where countries like Japan and South Korea abandoned nuclear weapons programmes in the 1970s.

There’s no telling if a second Trump Presidency will see him hacking at the roots of NATO. But if he does, many European states will inevitably rethink their defence—setting the clock back to the era before the organisation’s foundation in 1949. The world that emerges from the Second Cold War will have little resemblance to the one we inherited from its first iteration.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

For India, reflection on whether deepening ties with the United States, partly through Quad, are complicating our already troubled relationship with China. Whether we can realistically aim for stronger bonds with America than the Europeans possess.