Do we need a new Constitution? Lately, there has been much talk about that in India to go along with a new name for the country. The battle lines have been drawn — supporters of the proposition have pointed to how dated some of current Constitution’s provisions appear. Should liberalised India with expensive montessori education and even more expensive salons still declare itself “socialist”? Should laws relating to public health, shown up as woefully inadequate during the Covid-19 pandemic, continue to be made by state governments or should the Union government have these powers?

Opponents have been quick to claim that criticising the Constitution is disrespecting B.R. Ambedkar, the Chairperson of the Drafting Committee. Underlying their opposition is a fear that this is part of a larger design to establish a constitutional Hindu Rashtra by undoing equal citizenship and minority protections that Ambedkar and his fellow constitutional draftsmen had painstakingly incorporated.

Going forward, this debate will take many twists and turns. But while the future trajectory remains unclear, one hopes it remains informed by the past. Because our history holds an example of a truly secular constitution, one which comes from the unlikeliest of sources.

Also read: Don’t forget Savarkar used ‘Hindustan’. ‘Bharat’ became popular with Tagore, calendars, mandirs

A Hindu Mahasabha constitution

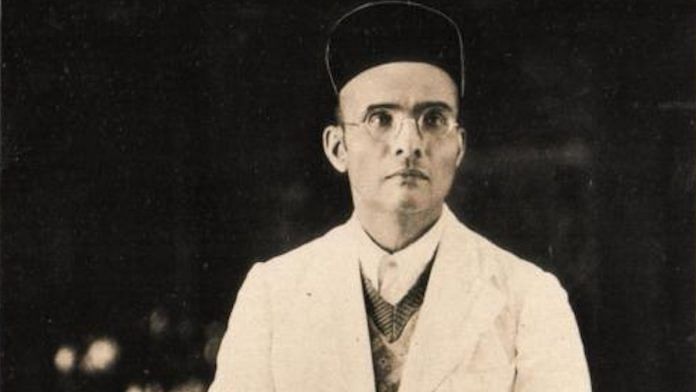

In 1944, the All India Hindu Mahasabha adopted the Constitution of the Hindustan Free State (CHFS) as a possible draft constitution. The Mahasabha was a party led by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Savarkar’s book Essentials of Hindutva shaped the party’s ideological line—only those who considered the land between the Sindhu and the Sindhu Sagar both their pitribhumi (fatherland-where one’s ancestors came from) and punyabhumi (holy land) could form the common brotherhood of Hindus. By definition, this included Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists and atheists and excluded Muslims, Christians, Jews. And despite some internal reservations, Savarkar himself had Zoroastrians as well.

But this exclusionary dogma was kept aside when drafting the Constitution. Written by four men, DV Gokhale, Laxman Bhopatkar, KV Kelkar and MR Dharmadhere, with a foreword by N.C. Kelkar, this is the only known example of an avowedly Hindu party setting forth its own constitutional ideas in concrete form.

The ideas in this Constitution were directly inspired by Savarkar’s speech at the Mahasabha session in Calcutta in 1939, where he outlined his views on the future constitution of India.

The contents of the CHFS, a fleshed-out version of that speech, might come as a surprise to many.

Also read: BJP bringing legislations opposition can’t afford to stall. Ayodhya, GST, women’s Bill, EWS

We, the people of Hindustan

The CHFS consisted of 111 articles and was much shorter than the eventual Constitution of India. Like the Constitution, it derived its legitimacy from the people and claimed to speak in their name. Unlike our Constitution, however, this draft placed much greater faith in principles of direct democracy. The framers of the CHFS believed that democracy in India had evolved to such a stage that people were entitled to “a direct voice in respect of their social and economic well-being and political destiny.” It thus made provisions for:

- Initiative– This was an innovative proposal by which citizens of the country could directly initiate legislation or constitutional amendments. A minimum number of voters would have to propose legislation, which would then be voted on by the whole adult population through a referendum.

- Referendum– Any initiative for legislation or any other significant law could be put to vote in a yes/no referendum before the entire adult population. This could happen when a minimum number of voters or a minimum number of representatives initiated the process.

- Recall- Arguably the most significant proposal, the right to recall, gave voters a right to depose their elected representatives before the completion of their term. One-tenth of the voters in a constituency would have to propose such a motion and it could lead to a representative being fired if a majority voted in its

To the framers of the Indian Constitution, these ideas were too radical. India had to be gently guided towards democracy and not thrust into it, as these proposals were attempting. Like much else in our present Constitution, the framers wisely decided to take things slowly and ignore these proposals.

Also read: Why India won’t see women’s reservation in effect until 2039—it’s about trickery

Neither India nor Bharat

The framers of the CHFS dwelt only briefly on the name for the country. “India” for them was “a meaningless term” and there was “absolutely no warrant in the past history of this country for styling it as India (sic)”. The present alternative “Bharat” was not discussed at all, despite copious references to the term in Sanskrit as well as several Indian languages. For Savarkar, Bharatavarsha, despite originating in the Vishnu Purana, was a suppression of “our cradle name “Sindhus or Hindus”. As a result, “Hindustan” was chosen in the Constitution without any dissenting voices.

Attached to the Indic term “Hindustan” was a distinctly un-Indic suffix “Free State” to give the country its full name—Hindustan Free State. In fact, the phrase was taken from Ireland, where the Irish Free State had successfully managed to free itself from colonial rule. The framers saw no contradiction in an indigenous name with a borrowed suffix. This was a recurring theme of the entire drafting process of the CHFS. As a matter of rhetoric, the CHFS was presented as the product of native Indian thought. But on matters of substance, they liberally borrowed from constitutions around the world.

Equally, they adopted the standard Anglo-American constitutional model of a government based on separation of powers with the legislature, executive and the judiciary checking and balancing each other. More indigenous ideas of panchayats and local councils, with a focus on moral rights and wrongs rather than checks and balances, were scarcely discussed. An independent Hindustan would take the best the world had to offer.

Also read: Udhayanidhi’s ‘eradicate Sanatana’ not a call to genocide. It’s internal critique of Hinduism

A secular State, no State religion

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of this constitutional framework was a ringing endorsement of India’s secular nature. Article 7(xv) of the CHFS provided that the Hindustan Free State would have no State religion. The possibility of a constitutional Hindu Rashtra was firmly shut.

Article 7(xi) gave every citizen the freedom to practice and profess their own religion and protect their own culture and language. There was no constitutional mandate to homogenise the nation. Equally, Articles 6 and 7(i) and (ii) guaranteed equal citizenship to all citizens with equal civic rights. No law could treat Hindus and Muslims differently.

There were clear political compulsions underlying these provisions. The Hindu Mahasabha had come into the political mainstream by forming a coalition government in Bengal during the Second World War. But after exiting that government, the Mahasabha became a fringe player in national politics. The Muslim League was on the rise and the RSS was fast emerging as the principal organiser of the Hindu community. The Congress was of course the centre of nationalist efforts. To remain relevant, the Hindu Mahasabha chose to be balanced and reasonable. The CHFS reflects that choice.

While history can never serve as an assurance for the future, it can certainly be a guide. With the fortunes of parties that belong to the Sangh Parivar now firmly in the ascendant, they would do well to look to their predecessors and the spirit that animated their constitutional thought while drafting the CHFS. That spirit was one of inclusion over ideology. Hindustan would be a country that every person irrespective of religious denomination could call home. The Constitution would reflect that broad-mindedness without being hemmed in by the narrow currents of parochialism or polarisation.

Opponents of the Sangh Parivar too ought to take note of the CHFS. Calls to draft a new constitution cannot automatically be conflated with creating a Hindu Rashtra. As Babasaheb Ambedkar himself said, quoting Thomas Jefferson, every generation should be free to debate its own constitutional ideas.

India today should be no exception.

Arghya Sengupta is the author of ‘The Colonial Constitution’ published by Juggernaut. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)