When Rajiv Gandhi started he could do no wrong. Halfway through his five years, he could do no right. His tenure had many chastening lessons in how mega mandates can make you smug and self-destruct. His record should be essential reading for those with brute majorities now, from Arvind Kejriwal, Narendra Modi and on to Vasundhara Raje, Naveen Patnaik and Mamata Banerjee.

Shekhar Gupta

Mayawati once raised an interesting question when under attack for her flurry of statue and memorial building for Dalit icons. Forward (“Manuwadi”) castes could hardly object, she said, as they had already filled our streets and parks with their leaders’ busts.

“Jahan dekho, Nehru aur Indira,” (wherever you look you find Nehru and Indira) and that was still understandable, she said.

What justified such iconography around Rajiv Gandhi that you couldn’t drive two miles in a city without passing two Rajiv Chowks? He was just an ordinary five-year prime minister who made no mark, she said.

For our generation of reporters, Rajiv was the first prime minister to be a 100 per cent contemporary. He joined politics when we were already on the political beat, he lost his mother, won an improbable mandate (415 in a house of 543), promised a new India for the 21st century, ushered in the computer age, wowed the world with his youthful sincerity (his immortal ‘I am young, I too have a dream’) that brought the house down in his address on Capitol Hill and launched India’s nuclear weaponisation.

Then, as spectacularly as he had achieved the mandate, he squandered it, the youthful promise of change giving way to cynical old politics that had defeat written all over it. And robustly confident military modernisation that was promising to make India a strategic powerhouse diminished to an arrogant, interventionist, neighbourhood bully in retreat. Was Mayawati, therefore, right to ask what she did?

You could answer the question by reminding her that her own rise, that of her politics, her mentor Kanshi Ram and his Bahujan Samaj Party, is owed to Rajiv. If he hadn’t demolished his own party’s underclass vote bank, neither she, nor the new heartland Mandalites, fortified by Muslims, would have risen. But my intention is not to have an argument with Mayawati. It is just that she asked a question that assails the mind of anybody who lived through Rajiv’s times, particularly as a political reporter.

Peace in our times

Truth be told, during the Rajiv Gandhi years, I was still too junior to cover a prime minister. I progressed from the age of 27 to 34 years between his electoral sweep in the winter of 1984 and assassination in the summer of 1991. I cannot claim to have known him well personally, or one-on-one professionally. I met him with some groups of journalists, mostly after he lost power. A reporter’s life is all about timing and coincidences. The irony in my case is that through Rajiv’s political life I was too young to cover him directly.

But by 1991 I was old enough to cover his assassination in detail, including from Sri Lanka, and pursue that story for long afterwards. At the same time most of my professional time in that decade was invested in covering his significant actions, policies and their consequences. These include his peace-making with rebels — Sant Harchand Singh Longowal in Punjab, Assam student leaders Prafulla Mahanta and Bhrigu Phukan, and Mizoram’s Laldenga.

The last two worked, but the first failed within months with the assassination of Longowal. Failure to protect his life, under Rajiv’s handpicked young governor Arjun Singh in Punjab, was his first setback. But as terror returned to Punjab, his fightback was firm and unyielding: his Operation Black Thunder in 1988 was a clinical success as much as Indira’s Bluestar was a messy, bloody conquest. But he never succeeded in putting the fire out. Punjab terror complicated the second half of his prime ministership further.

Khalistanis had become more powerful overseas, many key terrorists had escaped there; Kanishka, an Air India 747 was blown up in mid-air in June 1985. I also believe Rajiv spent many days and nights worrying obsessively about a threat to himself, but more to his family, from a top terrorist, Gurbachan Singh Manochahal, to the extent that when he was caught, he insisted on being personally briefed on his interrogation on a daily basis. At one point, Arun Nehru also persuaded him to allow the import of injectable “truth serum” to get more information out of captured terrorists.

The peace-making in Assam and Mizoram, however, endured. These were more large-hearted than Punjab, as he persuaded his party to cede political power in these states to former rebels. This is why peace in Assam and Mizoram is among Rajiv’s most valuable, and lasting contributions. My enduring journalistic memory of the finest side of Rajiv the statesman is the man smilingly waving at crowds in the Assam elections of December 1985 (after the accord), greeting him with “Rajiv Gandhi Zindabad, Congress Party Murdabad”. Funnier in that campaign was watching Amitabh Bachchan’s helicopter land mistakenly in an Asom Gana Parishad rally and the confusion the mixed reception caused in his entourage.

The Rajiv prime ministership can be divided into two-and-a-half phases. Sadly, the “half” was his best, the very first year. This was when he could do nothing wrong, when if he so wished, he could have changed the national anthem of India. I recall a conversation with my friend and mentor Arun Shourie then. As is usual with him, he had started raising questions about Rajiv. Watching him speak on Doordarshan once, Arun’s mother chided him for not even sparing such a nice man. “Are you looking for a prime minister or a son-in-law,” Arun asked. It is, however, precisely because of the love and expectation that he began with that Rajiv’s missteps led to rapid disenchantment. The remaining four years are two halves. Year two and three represent stutter and stall. The last two, 1987-89, were pure disaster.

His first, and probably the biggest political blunder had come early, in 1985-86 when he amended the Constitution and weighed in with the maulvis to overturn the reformist Supreme Court judgement in the Shah Bano case. As this caused a Hindu backlash, angered young and moderate Muslims (his young minister Arif Mohammad Khan quit in protest) he tried to over-correct at Ayodhya. The mandir movement was still in its early stages. But he allowed the shilanyas (foundation stone laying of the temple) and launched his 1989 campaign from there, promising Ram Rajya.

Earlier, he had unthinkingly put the Mandal Commission report, submitted in 1985, in cold storage. Net impact: he had alienated Muslims, Hindus and the backward castes. Advani ran away with the Hindu vote, OBC leaders like Mulayam and Lalu rose, angry Muslims built “secular” coalitions with them and Kanshi Ram moved in with his Bahujan Samaj Party, collecting Dalit voters. Although later it would be fashionable in the Congress to blame P.V. Narasimha Rao for it, it was Rajiv’s politics that started destroying the party’s vote banks.

In Rajiv’s first year even his gaffes made us smile lovingly, except the “when a big tree falls, the earth shakes”, although that was before he was elected. He could never pronounce Sant Longowal’s name right, although it was quite simple with four consonants linked by three vowels. He called him “Longewala ji” instead. By his fourth and fifth, he could say nothing that didn’t become a joke, “hum jeetenge ya loosenge” being the most stunning of these although it was a mere slip during a downhill election campaign. There were some before that, his description of opposition MPs as limpets, and worst of all in my book, but by now forgotten because these were pre-Internet days, his dismissing S. Jaipal Reddy’s attacks on him in Parliament over Bofors with “he doesn’t have a leg to stand on”.

From Mr Clean to Bofors Chor

His blunders, some of youthful exuberance and frankly many sins of commission — Shah Bano to shilanyas, the Bombay AICC session speech (threatening to purge the Congress of power-brokers) to the whining “nani yaad dila denge” at Boat Club when he was under siege, from the promise of regional power status to a flailing neighbourhood bully in ignominious retreat (Sri Lanka), from Mr Clean to Bofors Chor, and from the great political reformer to just another dynast in deep panic who brought in as his deputy in the party, loyalist Kamalapati Tripathi, a personification of exactly what he had said was wrong with the Congress.

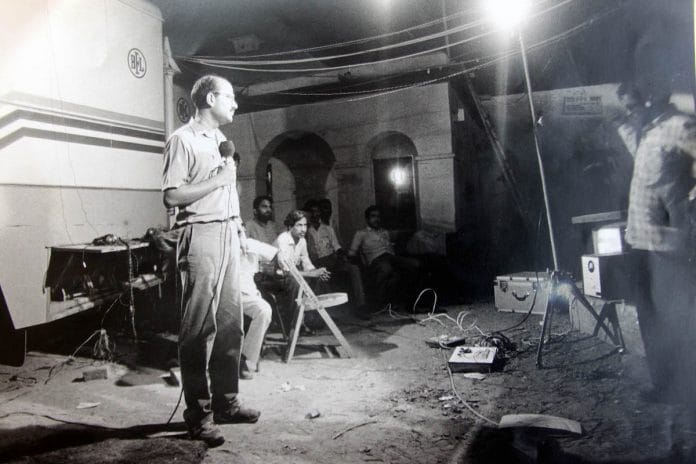

His power and moral stature ended the day his most trusted defence minister V.P. Singh resigned, won the resultant by-election in Allahabad and launched a campaign that installed him as prime minister just 18 months later. I covered that by-election in detail and the counting day was, in fact, also my first experience of live reporting for TV news, on Doordarshan’s Election Special.

So formidable was Rajiv’s mandate that how he lost it has become the dominant story. But his score sheet is not all splattered in red ink. His modernising mind, love of the computer, evangelising panchayati raj and devolution of power are significant contributions. In his own hesitant way he had started to reform India’s economy at least until V.P. Singh was still his friend, and finance minister. In 1987 India faced the worst drought of the century and, as T.N. Ninan noted later, it became the first year in history that India’s economy grew in spite of the drought. This is because the Rajiv era saw a rise in the share of services and industry in our GDP. Significant changes in foreign policy saw him warm up to Ronald Reagan. Caspar Weinberger came calling in 1986, the first US Secretary of Defence to do so in decades. Let me, however, talk in greater detail about his contribution in one key area I covered closely.

Rajiv brought a refreshingly young, and energetic view of Indian military and strategic power and was more willing to employ it than his “perfect gentleman, nice guy” demeanour would have suggested. He launched a massive wave of military acquisitions. Such was the pace that by the end of 1985 I had already written a cover story in India Today magazine on India’s defence modernisation and one of the newly acquired Mirage-2000s was the lead visual. My personal story of that assignment is a near tragedy as a Mirage, making low and very slow passes at Gwalior went into a momentary stall so low that it was lost in a cloud of dust and we presumed the worst. Until, a micro-second later, it screamed out of the “cloud”, afterburners spitting flames almost at our eye level. The pilot’s skill and presence of mind had saved the day as he engaged the afterburners for an added surge of power and broke his stall. Wing Cdr Ajit Bhavnani, who was raising India’s first Mirage squadron, was as relieved. He rose to be an Air Marshal commanding India’s strategic forces, and we became friends for life.

Sri Lanka wasn’t his Stalingrad

Time magazine too put Rajiv’s military thrust on the cover with the headline “Super India” and a picture of INS Viraat. Rajiv shared with his old friend, and most trusted aide, Arun Singh a love for gadgets and instruments of war with a teenager’s enthusiasm. His five years marked the most relentless military modernisation in our history, and I don’t say that lightly. Regrettably, it also destroyed him as scandals broke out soon enough.

The Rajiv-Arun Singh partnership was complemented by the rise of two unusual Indian soldiers: General Krishnaswamy Sundarji and Admiral R.H. Tahiliani. Even as western army commander (Operation Bluestar took place under his watch) Sundarji had acquired fame for his radical ideas on junking old concepts of static warfare, endless slugfests with tanks and artillery where little ground was taken or lost and each Army was able to stall the attacker at its DCB, the military-speak for a canal or drain, a water obstacle called Ditch-cum-Bundh. His idea was now a much faster war-fighting profile where mobile juggernauts will roll on, over the DCBs and beyond without stopping to catch its breath, replenish ammunition, or lick its wounds.

This appealed to Rajiv and Arun Singh and a massive re-equipping, with tanks, infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) and of course Bofors artillery was initiated. Mechanised infantry units were formed as assault replaced defence as the buzzword. Sundarji’s more radical ideas, RAPIDs and RAMIDs (Reinforced Army Plains and Mountain Divisions) were accepted. Even in the mid-80s, Sundarji and Arun Singh conjured up the dream of an airborne assault division and one, the 54th, in Hyderabad, was earmarked for the role even if the helicopters needed for it are still not in place. Air power multiplied. Mirages were followed by more of the new MiG series, 23, 27, 29 and trisonic 25s.

Tahiliani was allowed to reconfigure India’s naval doctrine from coastal defence and limited sea denial (in the Arabian Sea) to a blue-water profile. When Rajiv went for one of his storied vacations to Lakshadweep, Navy warships lurked close by in attendance! For nearly three decades now Rajiv has been attacked on Bofors. But it is still India’s frontline artillery gun and a game-changer. Such was Rajiv’s impact that even today in a conflict, Indian armed forces will field a lot of the equipment he ordered at least a quarter century ago. Footnote: under Rajiv, India’s defence budget crossed the Lakshman Rekha of 4 per cent of GDP, reaching 4.21 per cent at its peak.

Military power is heady and amateurs can get carried away. Which is what happened with the Rajiv-Arun Singh duo under the influence of Sundarji’s dash. He wanted to check out his new mobile warfare concepts in the mega war gaming exercises (Brasstacks) in 1987, and even as it alarmed the Pakistanis, he launched another set of “new-concept” exercises: Checkerboard (facing China) and Trident, in the northern Kashmir area. Suddenly, it looked as if India was poised for a two-front war on Pakistan and China. As alarm spread in global capitals, Rajiv did finally calm things down, appointing V.P. Singh defence minister, thereby restraining Arun Singh, but he was still not cured of the headiness of his new military muscle. He loved force-projection in the neighbourhood. He sent paratroopers in his new Il-76s and AN-32s to help defeat a coup attempt in Maldives in 1988, and embarked on a full-scale peace-making intervention in Sri Lanka by sending in the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF).

The Sri Lankan intervention was actually a good idea. At great risk to himself he had decided to fight like big powers would, a strategic battle far from its shores. Sadly for him, such military adventures need to have wide popular support, which it didn’t. In fact, by the end of 1987, when IPKF happened, he had lost much political capital. He got the blame as the Army suffered some early setbacks and it added to his spiral of crises.

I believe, however, that in principle he had done the right thing. But he had scared the LTTE enough to fear his return, and assassinate him. I am willing to break rank with an entire generation of commentators who call Sri Lanka his big folly, even if it cost him his life. I’d rather go by what my friend and RSS ideologue S. Gurumurthy once told me, that in choosing the method and place of his tragic death, Rajiv actually finished whatever was left of the Tamil separatism and sympathy for LTTE in India. That is why Rajapaksa was able to finish the job 18 years later and Tamil Nadu looked the other way. His other positive contribution on the strategic side, for which he is given no credit is in launching India’s nuclear weaponisation. In a series of events I have recorded elsewhere, beginning at an IAF firepower display at Tilpat near Delhi, where he called top civil servant Naresh Chandra, and mandated him to head the weaponisation operation. The result, ultimately, was Pokhran-2. Rajiv also made two significant innovations in national security by forming the National Security Guard (NSG) and the Special Protection Group (SPG).

Irony is a much overused, and misused, word in all journalism. So here I am again, underlining the greatest irony of Rajiv’s times, the man who did more to enhance India’s military and strategic muscle, was destroyed by one of the instruments he bought to make this possible. But Bofors was just the most visible symbol of Rajiv’s failures. In a series of long, on-record conversations with Arun Singh (who became a recluse and rarely, if ever, speaks), I could see what failed Rajiv. One, he had a poor choice of people. He built an inner circle of talented friends around him. A third of them were sincere and honest, Arun Singh included.

The rest were mostly crooks. Together, they gave Rajiv’s regime an elitist, aloof, apolitical image. Second, much as he started out by cursing the Congress party for all that was wrong with it, he acted no differently. His response to Bofors was imperious, dismissive first, then of self-righteous outrage (neither I nor any member of my family has taken any commission) and finally cynical and manipulative as he fixed every probe, stage-managed the Joint Parliamentary Committee under loyalist B. Shankaranand. In his core group of friends, only one, Arun Singh, counselled him to be more open-minded and transparent but was contemptuously dismissed, repeatedly with a counter-question – why are you getting so exercised? What is it that I can give you? Name the portfolio you want. Meanwhile, most of his other friends, starting with Arun Nehru, had disappeared.

A more reformist PM?

This is not a historian’s critical reconstruction of the Rajiv era, nor his definitive political biography. He is among our most fascinating leaders sadly more because he ruined his mandate of 415 so badly in five years that the highest his party scored in 30 years after that was 232 in 1991. He initiated the destruction of his party’s heartland vote banks and the rise of Dalit, Mandalite forces and, more importantly, of the BJP as India’s pre-eminent party upstaging the Congress. My last conversation with him took place at a highway dhaba just as we crossed the Ganga from Buxar in Bihar towards Varanasi during the 1991 campaign. He listened to a couple of young villagers talk about their hopelessness, responded with sensitivity, sounded as if he had imbibed the right lessons and was going to be a very different, more reformist, economy-oriented prime minister if elected this time. This was not to be as this conversation took place just a day before he died in Tamil Nadu.

Rajiv was a patriot who ruled at a very tough juncture, his degree of difficulty unfairly masked by the size of his mandate. He rose in a traumatic moment of extreme personal violence, the assassination of his mother. He died seven years later, becoming history’s first prominent victim of a human bomb. In the intervening seven years he did much good and bad to leave behind a legacy. No, Mayawati-ji, he wasn’t just another, non-entity five-year prime minister.

Nice Share! Well Done, Please Keep writing

Ive never happen to be concerned with On Rajiv Gandhi

birth anniversary: How to squander a mega mandate.

Somewhat, While i observed that not long ago the majority began worrying about the idea, right.

And still, I actually don’t really think I`m revised on it.

Am I Going To have some facts from you?

Fine, fair summation – especially for younger readers – of what started out as India’s Camelot, but ended in disappointment. Rahul Gandhi should read this column, with a sense of introspection, ask himself, Can I essay a better journey ?