Terrorism is not new to the history of the world but the story of Punjab is quite interesting.

In Punjab, shades of collective organised violence have existed since the beginning to the end of the 20th century. All these acts were not given the negative attribute of terrorism for obvious reasons. Though there is no such thing as essentialism implicated in this historical experience, it seems that throughout the 20th century, there was an organised violent struggle almost every two decades.

The first three pre-Independence movements—led by Ghadar Party, Babbar Akalis, and Bhagat Singh and his comrades—used violence to attain freedom for the country. The first two were confined to Punjab, though Vishnu Mahesh Pingley from Maharashtra and Ras Bihari Bose (Bengal) were involved in the Ghadar Party movement.

The fourth began in 1948 when communists broke away from the Parja Mandal movement, which was spearheading the peasant struggle in the PEPSU (Patiala and Eastern Punjab States Union) region and started an armed struggle against big landlords known as Biswedars.

In 1967, when the Naxalite movement started in West Bengal, many Punjab communists broke away from their parties and joined the movement. From 1967 to 1972, there were violent attacks on the big landowners and police informers. The Punjab government reacted ruthlessly and succeeded in suppressing it. It is interesting to note that some of the survivors of the Ghadar Party and Babbar Akali movements joined the Naxalites, the prominent among whom was Baba Bujha Singh who was allegedly tortured to death.

The economic situation of Punjab was quite different from the rest of Indian states. This was the period when the Green Revolution — the phenomenon of high agricultural productivity through chemical fertilisers, hybrid seeds and irrigation — occurred. The Green Revolution brought prosperity and peasants lost interest in other kinds of possibilities. The Naxalite movement remained limited to the intelligentsia.

The peasant prosperity, however, began to show its effects in the form of political changes. The Jat Sikhs who remained in majority in most political parties (sans BJP and later BSP) began articulating Sikh issues in which the Shiromani Akali Dal (Akalis) got fully engaged.

In 1972, Giani Zail Singh of the Congress became the chief minister of Punjab after Akali-led coalitions had ruled without completing full terms. Zail Singh tried to steal the Sikh agenda showing that he cared more about his fellow brethren, threatening the Akalis. This was the time for the Anandpur Sahib resolution, which subsequently was claimed to be the document for Centre-state relations. However, this issue did not pick up heat during the 1970s.

When the Janata Party came to power in 1977 at the Centre, Parkash Singh Badal became the chief minister of Punjab heading a coalition government. Experts say that Congress leaders, particularly Zail Singh, helped Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the head of the Damdami Taksal, a Sikh seminary at Chowk Mehta near Amritsar to gain prominence.

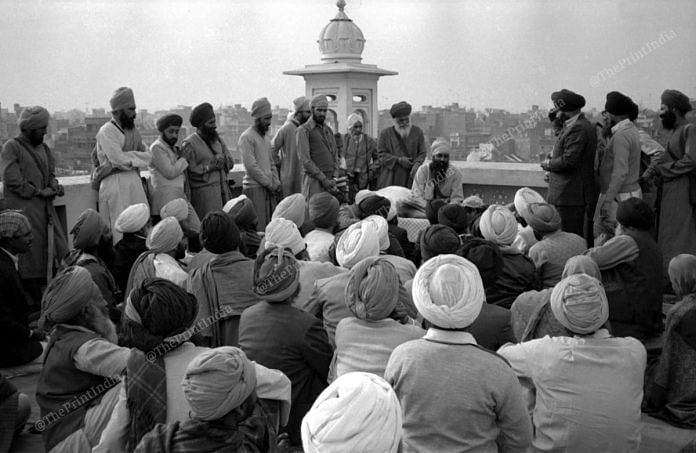

The situation began to take a dramatic turn when an anti-Nirankari sect campaign—started by Sant Giani Kartar Singh Bhindranwale—was not only continued by his successor, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, but also became aggressive. It exploded on 13 April 1978 when followers of Bhindranwale, also consisting of the followers of Akhand Kirtani Jatha, clashed with the Nirankaris in which 13 members of the former group and three of the latter were killed. Thus began a violent campaign initiated by Bhindranwale’s followers in addition to which Babbar Khalsa came into existence which was organised by Sukhdev Singh, the devotee of Akhand Kirtani Jatha.

As the killing of targeted individuals continued to escalate, the situation in Punjab deteriorated. In 1981, after the killing of Lala Jagat Narain, former minister of Punjab and chief editor of Punjab Kesari group of newspapers, Bhindranwale was arrested resulting in a clash between his followers and Punjab Police in which 18 people were killed. Bhindranwale was released shortly after but the situation in Punjab did not improve.

In the beginning, both the Congress and the Akalis were hopeful of manipulating Bhindranwale in their favour, but he progressively demonstrated his autonomy. Anticipating serious state action against him, he moved to the Golden Temple complex in Amritsar where he remained until his death in Operation Blue Star in 1984.

Also read: Amritpal’s rise and fall expose a vulnerable Punjab. Minority bashing will boost radicalism

Phase and face of terrorism

The period 1984 and 1993 was truly characterised as a phase of terrorism perpetrated by militant organisations. Prominent were the Babbar Khalsa International, Khalistan Commando Force (which was later divided into three factions), All India Sikh Students’ Federation (also fragmented into different factions), Khalistan Liberation Force, Bhindranwale Tiger Force of Khalistan, Dashmesh Regiment, and Khalistan Armed Force.

This period witnessed major events including the assassination of Indira Gandhi followed by anti-Sikh riots, the declaration of Khalistan by Sarbat Khalsa in 1986, bombing of Air India plane coming from Canada, assassination of Sant Harchand Singh Longowal after the accord with Rajiv Gandhi, formation of Surjit Singh Barnala-led government and Operation Black Thunder. Punjab remained largely under the governor’s rule, but nothing could control the militant activities. The Barnala government was dissolved in 1987 and governor’s rule continued till 1992, when following fresh elections, Congress’ Beant Singh became the chief minister. Within a year, terrorist activities virtually stopped. The only major incident was Beant Singh’s assassination in 1995.

Two questions need to be addressed. First, what led to the sudden disappearance of militant activities; and second, what are the possibilities of their re-emergence?

In the beginning, issues concerning Punjab, such as Chandigarh, river waters, autonomy for states, etc. were understood as real and supported by the Sikhs in general. Later, when the violence began to increase in the early 1980s and the ‘Dharam Yudh Morcha’ primarily articulated the demands of the Sikhs, many people began to withdraw from it.

During the entire militant movement, the Hindu-Sikh unity was not seriously breached by the discourse it created. The nature of terrorist activities did not have any focused target. It opened all fronts, such as state machinery, political leaders, rich farmers, police informers and intellectuals. As a result, the well-off rural Sikh families began to migrate to the cities and some of the Hindu trading families migrated to cities outside Punjab.

The worst affected families were of those Sikh farmers who lived in the farm houses outside their villages. And a time came when Sikhs began to inform the police. There has been a view that it began to happen when the farmers were threatened in a way that even their daughters could not be protected from their lust. It is alleged that in the beginning, the Sikh boys who joined the movement were serious about the cause, but later, young boys who joined it were allured by the gun culture. Additionally, there were too many organisations of the militants to have any singularity of direction. It was bound to degenerate into mindless killings.

With the posting of KPS Gill as the Director General of Police (DGP) in Punjab, the anti-militant campaign turned serious, because the police force began to work cohesively due to certain other reasons than the arrival of Gill. Fencing was done at the border, which prevented the smuggling of arms and ammunition from Pakistan.

Also read: Religious intolerance main driver of insurgency in Punjab of 1980s. State’s watching it again

Times have changed

Today, the chances of the Khalistan issue taking the shape similar to what happened in the 1980s seems least probable. Both political and economic conditions have undergone major changes. From 1997 onwards when the Akalis dropped the discourse of “Panth is in danger” in favour of development agenda owing to its alliance with the BJP, Sikh issues were pushed to the background until the 2022 assembly election, when the issue of imprisoned Sikhs (Bandi Singhs) resurfaced in Sangrur parliamentary constituency. Economically, there has been a major shift towards international migration among the youth.

However, there are two groups about which it is possible to speculate in terms of any future activity, which seems to be occurring at present in a combined manner with limited impact on the Sikh masses. It is important to raise a query with regard to the former militants who strived to live a normal life after everything is over. Some of them have joined mainstream political parties, such as Akalis and Congress, whereas many of them resumed their normal life. However, some of them have remained active and engaged in religious issues of various kinds. After about 30 years, most of them are old and have lost their will as well as energy to become active.

The second is the element among the overseas Sikh, who have continued to make noise about Khalistan. The case of Amritpal Singh seems to be suggesting that some Sikhs abroad are still making an attempt to revive the movement by financing it. However, the Indian State has also undergone a qualitative change with a zero tolerance policy towards separatism and terrorism. Above all, times have changed. Now there is no stoic Jat Sikh boy who could undergo the harsh life of an armed activist; the young have now turned epicurean.

Paramjit Singh Judge is a former Professor of Sociology, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)