The “Indian food is unhygienic” myth needs a serious reality check. Its shelf life is achingly old and racism-adjacent.

Earlier it used to be White people who would diss Indian food culture. Now a Chinese woman has shown an Indian vlogger dirty street food videos to embarrass him.

It’s time to call this out for what it is.

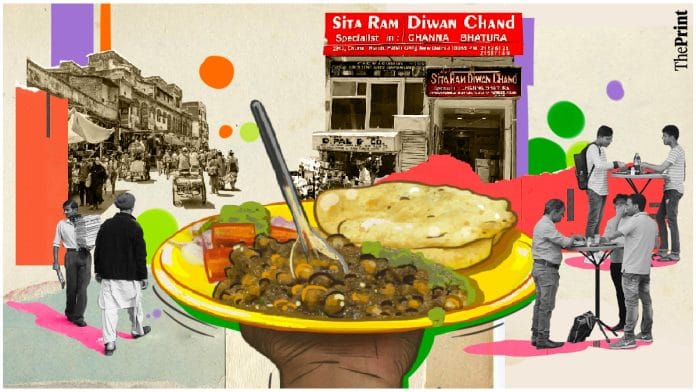

Indian cuisine is rooted in fresh ingredients, rich spices with antimicrobial properties, and time-tested cooking methods. We are not a freeze-and-serve fast food nation.

For the hygiene issues, it’s not exclusive to Indian kitchens and street stalls. My recent international travels exposed me to a fact: street food, irrespective of the country, is unhygienic.

It’s the same street food story worldwide—sometimes even wilder. It’s not an India problem.

Sure, maintaining hygiene would be nice, but have you seen the budget? The limited resources mean food is often marinated in a hint of contamination.

And, if someone had a state-of-the-art kitchen, do you think they’d be flipping patties at a street stall? Whether it’s India or anywhere else, street food culture thrives on a bit of grit.

But, somehow it’s only Indian food facing this stigma of being unhygienic.

Agreed, Indian chaat stalls are a daring adventure, where the same hands that handle cash whip up your pani puri—topped with some atmospheric dust and maybe a rogue fly or two.

But let me tell you, Thailand and the US are no different.

Thailand street food has some amazing skewers, but along with the grilled pork you’re also getting an extra pinch of urban pollution and whatever is on the chef’s hands after chopping chilies barehanded. Please note, even they don’t wear gloves while handling the meat.

Or take New York’s hot dog carts, where the meat simmers all day in water that’s more seasoned than a cast-iron skillet, probably with hints of every past day’s sales.

Culinary roulette

Street food as a concept is an adventure of taste and tolerance. It isn’t about hygiene; it’s about “authenticity.”

There’s a thrill in thinking — “will this kebab treat me right, or will it introduce me to the city’s finest restroom?”

It’s culinary roulette, where taste and guts are put to the test. And as they say, what doesn’t kill you (or your stomach lining) makes your street food story even more interesting.

However, I cannot miss mentioning a 2014 article published in The Guardian, where a reporter narrated her experience of getting Mumbai’s street food lab tested.

Sana Merchant bought a plate of pav bhaji from a street stall, which had a busy railway station to the right and a bus depot to the left. After every 10 minutes, a new bus blew exhaust all over the food, which was cooked and stored in the open facing a public toilet.

“The man preparing the dish was cooking it in an open space without wearing gloves or a hat. He was drenched in sweat. I ordered a takeaway pav-bhaji. To my surprise, the bhaji (cooked vegetables) came packed in a plastic bag, while the pav (bread) was wrapped in a local newspaper,” she wrote.

However, when the lab report came, the food sample turned out to be suitable for consumption. It didn’t contain bacteria like salmonella, E coli, or shigella.

It is understandable that tourists are wary of street food in India. But sometimes, street food made in front of you can be much more hygienic than the food in a restaurant whose kitchen you cannot see.

Also read: Indians have gone too far with fusion food. Gulab jamun tiramisu is perverse

Reality of restaurants

In the last one year, I have visited over a hundred restaurants in Delhi NCR alone.

And, I have seen both sides of the coin — spick-and-span kitchens in Olive and One8 Commune, to some really dirty ones (won’t take names).

But, again, the story is the same in other parts of the world too.

Michelin-starred chef Gordon Ramsay’s shows Kitchen Nightmares and 24 Hours to Hell and Back had exposed filthy kitchens in the US.

From expired food to dirty kitchens, contaminated meat to piles of dirty utensils — this side of US kitchens made me puke.

In 2016, a bunch of restaurants in Australia were revealed to have poor hygiene practices, including lack of hand washing facilities, accumulation of dirt and food waste, and rodent faeces in flour and bread crumbs.

Later, the restaurants were heavily fined.

With the inflow of crowd, cooking food in large quantities, the pressure to make profits, cost cutting and so many other factors influence restaurants’ hygiene practices. And, if it’s a new restaurant, the job is even tougher.

I can bet my life’s savings, which aren’t much at this point, that if restaurants start to practise all hygiene rules, they wouldn’t make profit at least in the first five years.

Now, hygiene is, of course, non-negotiable. However, my issue is with stereotyping a particular cuisine.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Are you OUT OF YOUR MIND? One can eat street food in nyc and BKK without thinking.In India the hygene standards are absolutely horrible.Look around ANY street vendor,there will be flys galore,dogs,cats and other mongrels incuding rats hovering.The Print shoud fire you for spreading wrong info.Indian street food is inedible and totally unhygenic.